Photo: Nils Klinger

A Play with Recourse and the Staging of Eternal Return

By Nicolas Bourriaud

It is not difficult to imagine a humanity for whom a state of consciousness determined by chance has become the social status quo – the result of the immense flow of information produced every day exceeding the individual’s capacity to absorb it. It is likely that this chaotic mental state combined with the golden rule of Capitalism – to further accelerate the super-speedy circulation of increasingly short-lived products – would also affect the profession of curator. In fact, what has been demonstrated progressively in major exhibitions in recent years is an increasing incapacity to glean a discrete idea from the artworks included and, even more than that, the refusal to take up a position in relation to contemporary art production, to such a degree that even the slightest aesthetic statement is taken today to be »sectarian«, »reductionist« or »intolerant«. But that was once precisely the function of documenta: every five years it was possible as a visitor to profit from the (necessarily subjective) view of the curator on the development of practices and forms in the current production of art. Let’s remember that the curator, like the psychoanalyst, derives authority only from him- or herself. This principle of Lacan (also, by the way, like psychoanalysis) has been passed over in favour of a logic of community: instead of asserting knowledge and, perhaps confronted with the objection that he has learned it only from his own experience, the curator prefers to lay claim to the ironclad laws of his community. In short: today it is better to think with and like the others if one wants to sleep at night.

With his documenta in 2002, Okwui Enwezor showed that an ethnographic perspective on the model of the documentary could help him question globalisation. In 2007, Roger Buergel saw documenta as a direct means of expanding the archive. This enabled him to mix forgotten avant-gardes with exotic préciosité, while one of the exhibition’s purported themes – which ultimately was not dealt with – was the »experiment and the city as a territory of possibilities« – in other words, more or less everything that could be exhibited. Five years later, it seems as if documenta has not progressed in terms of engaging the aesthetic debate. Even the edition before this one was totally dominated by compulsive backward-looking and politicised rhetoric, and now the exhibition curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev also articulates itself around four pre-defined cornerstones, as if a museum-style view of art has been frozen in marble: »On stage. I am playing a role; I am a subject in the act of re-performing. – Under siege. I am encircled by the other, besieged by others. – In a state of hope, or optimism. I dream, I am the dreaming subject of anticipation. – On retreat … « (Curator’s Statement). Re-performing the past, resisting, nonetheless hoping and retreating from the world, indeed: according to Christov-Bakargiev, it seems that artists of today are all showing signs of severe neurasthenia. That may also explain the recourse to other fields of thought, such as »physics and biology, eco-architecture and biological agriculture, renewable energy, philosophy, anthropology, economics and political theory, linguistics and literary theory, literature and poetry«. While the last documenta invited the chef Ferran Adrià (a genuinely creative spirit, by the way), the current one has liberated itself from such »frivolities« in order to devote itself to serious matters: quantum physics – by way of experiments accessible to the viewer. In both cases the question arises: where is the lively intellectual relationship between such research and contemporary art supposed to be? But even the rest of the exhibition provides no answer to that. And its general theme has so many other parts branching off that it remains unclear.

Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Photo: Roman März

In what appears to be required practice today, the ground floor of the Fridericianum clearly shows the rhetorical character of the exhibition. Here, Ryan Gander’s rush of air fills the emptiness of the obligatory »tabula rasa« room (cf. São Paulo Biennale 2010), while Kai Althoff’s rejection letter in a glass case is obviously exhibited to give material form to the relationship between curators and artists, and Julio González’s contribution to documenta in 1954, which has been reconstructed according to a photograph, appears as a fetish from the past. When it comes to rediscovering forgotten artists of art history, another required practice for biennials in the 00s, this documenta turns out to be at its most interesting. Works by Maria Martins, Emily Carr, Margaret Preston, Charlotte Salomon or Korbinian Aigner, for example, make it really worth the effort of travelling to Kassel. It is symptomatic that documenta once more faces the past in this way – rather than taking a committed view of art in the future in the way of the exhibitions by Harald Szeemann and Okwui Enwezor.

It is genuinely difficult to pinpoint any kind of guiding principle or point of crystallisation. To such an extent, the work by Pierre Huyghe, a fascinating, living structure inspired by Bioy Casares’ novel The Invention of Morel (1940), seems to both obliterate and summarise the entire documenta: a play with recourse and the staging of eternal return, a manifesto of a poetic reenactment that is examined in all its unfathomability. Huyghe’s work functions as a material allegory of the contradictions in today’s art world. There are also two more museological presentations that stand out. One of them is the remarkable installation by Haris Epaminonda & Daniel Gustav Cramer; the other is by Kader Attia, another representative of the aesthetic of the fragment. His work is very impressive, although the installation would certainly have benefited if the documentary material had been presented in a less gigantic, Hirschhorn-like way. These works as well as others, which cannot be mentioned here for reasons of space, are a reminder that the most important task of an artist is to take a point of view. This point of view, anchored in a precise place in the intellectual, social and ethical landscape, accounts for the determining contents of his or her engagement and promises that a politics of art will remain relevant.

Translated from the German by Nelson Wattie

NICOLAS BOURRIAUD is co-founder of the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, served as curator at Tate Britain in London, and has been the director of the Beaux-arts de Paris since 2011. His recent exhibitions include the Tate Triennial in 2009 (Altermodern) and the Athens Biennial in 2011. His most recent book, entitled The Radicant, was published by Lukas & Sternberg in 2009. He lives in Paris.

Reenchanted, Object-Oriented

By Fionn Meade

Intellectual, grand, and expected to outmaneuver the art market, the visionary task of documenta regularly overshadows the specific artworks and projects presented. There are forceful artist commissions, co-conspirators (d13 used the term »agents« for its impressive curatorial team), extended anticipation, heightened compression, and the essential drama of the location, genesis, and lineage of documenta as a distinctly postwar German invention. The exhibition is supposed to offer a frame that is globally informed and politically attuned while delivering a spectacle with enough magnetic pull and hyperbolic sensitivity to be seen as forecasting our cultural condition. It is this expectation for it to historicize the moment that has lead to proclamations like Roger Buergel’s (director of documenta 12), that it is the most important exhibition in the world. Built to be a bold prognosis, the foundational spin of d13 was tied to a speculative turn away from understanding the world according to human thinking and linguistic reason. De-emphasizing textual and political critique in favor of a materiality that is by turns reenchanted, object-oriented and phenomenal, d13 embraced »precarity« and »openness« in order to generate »space as the region of the possible« – ostensibly separate from the dynamics of nationality, power, and reductive argumentation.

Engaging Kassel’s site-specificity so as to produce »a polylogue with other places« comprised d13’s initiative and informed its stated themes of »Siege, Hope, Retreat, and Stage«. Taking the Arab Spring as an inspiration, »Hope« consisted of a month-long series of talks prompting an exchange between Egypt and Kassel. Likewise, being »under siege« meant funding artist commissions based on visits to Afghanistan. A tactic not unrelated to the de-occidentalized »platforms« of Okwui Enwezor’s documenta 11, the dialog with Afghanistan included a separate exhibition as well as workshops in Kabul, while »Retreat« became an invitational gathering at The Banff Center in Alberta, Canada allowing reflections on central questions that arose during the five-year process as well as the exploration of »new spaces of openness, freedom, and possibility«. That said, only the Afghanistan-specific commissions on view in Kassel were made available to visitors, leaving the »Stage« in Kassel to manifest d13’s themes.

Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Photo: Roman März

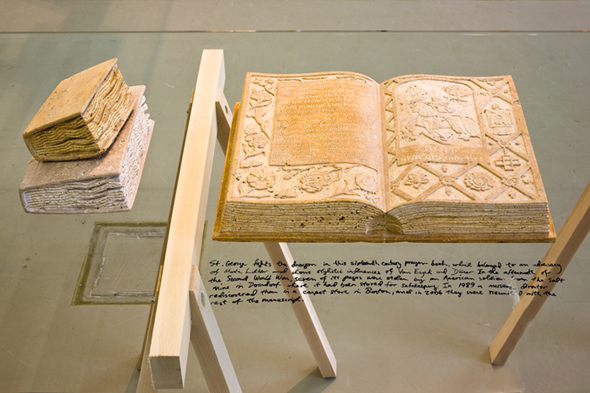

Ecologically minded projects occupied the natural history museum setting of the Ottoneum – including earnest works by Amar Kanwar, Mark Dion, and Maria Thereza Alves – while elsewhere in the exhibition scientific displays by some of today’s leading theorists also played a prominent role – including somewhat hagiographic nods to quantum physicist Anton Zeilinger and epigeneticist Alexander Tarakhovsky as well as overlooked visionaries like pomologist and Holocaust survivor Korbinian Aigner and computer pioneer Konrad Zuse. The museological rhythm extended to an overly literal zoological tribute to theorist Donna Haraway constructed by artist Tue Greenfort as well as to the ethnographic framing of Kader Attia’s installation The Repair from Occident to Extra-Occident, 2012. In the latter, African fetish objects mended with patchwork-like scars and visible stitches instead of authenticating or restorative conventions were combined with a projection of archival photographs detailing the surgical repair of maimed soldiers during World War I. Resulting in a compelling though forced juxtaposition, Attia’s reassembly adopts a strident yet provisional empiricism that also plagued works by Goshka Macuga and Francis Alÿs. The most persuasive project to engage the expedition-like »Under Siege« was Michael Rakowitz’s archeologically-minded installation What Dust Will Rise? (A cosmology toward a project for dOCUMENTA13, Kassel/Kabul), 2012. Working in the area of Bamiyan, Afghanistan, where sixth-century Bamiyan Buddha statues were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001, Rakowitz presented a series of books carved from Bamiyan stone that reference lost volumes from the Fridericianum’s library (bombed in 1941) as well as other sacred texts. Identified by hand-written labels inked directly onto glass cases, Rakowitz’s wunderkammer manages a weird stratification, moving past connotations of reparation into ongoing collaborative, political, and material antagonisms.

FIONN MEADE is a curator and writer living in New York City.

Photo: Roman März

Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Photo: Nils Klinger

Photo: Henrik Stromberg

Photo: Roman März

Photo: Nils Klinger

Photo: Nils Klinger

Photo: Nils Klinger