Sublime Riuscita

Pier Luigi Tazzi

The summer of 1986 was a particularly hot one in Holland. One evening, Saskia Bos, the curator of Sonsbeek that year, invited us to dinner at a villa in the countryside between Arnhem and Otterlo, nestled among magnificent Dutch landscapes such as one sees in the paintings of Jacob van Ruisdael. It was there that I met Franz West for the first time – we just happened to be seated next to each other at the same end of a large table. He was dressed in a combination of acidic colours that I would later recognize in some of his works, which meant that his appearance for me was not so much bizarre as uncanny. He began to tell me about the importance of elegance in dressing. Later, he also shared with me his complete distaste for the Biedermeier style.

I knew who he was, since I had seen his works: not only in those days at Sonsbeek 86, but also earlier, for the first time, at an extraordinary exhibition curated by Harald Szeemann and inaugurated less than a year before at the Kunsthaus in Zurich. I had loved that exhibition, with its wonderful haiku title: »Spuren, Skulpturen und Monumente ihrer präzisen Reise«. Next to works by Medardo Rosso, Alberto Giacometti, and Louise Bourgeois, Franz West’s pieces were decidedly dissonant with the otherwise cohesive ensemble: approximate rectangular shapes tilted vertically and uniformly painted, with uneven surfaces flexed inwards along some of the edges. The colour, applied in an uncertain matter, was impure and alluded to some kind of splendour, initially lost and now ostentatiously and shamelessly returned.

Only a little later would I discover his passstücke, a sort of unlikely prosthesis designed for a body with which it would never fit. Sculptures intended to be handled rather than observed, made for action, meant to be activated through both physical and mental interaction, rather than the imagination; everything indulged in a flagrant immediacy. Hence his seats, chairs and benches made of recycled metal, fruits of his collaboration with other artists, such as Mathis Esterhazy, who would continue to work with him in the years to come. From his favourite materials, plaster and papier-maché, he shaped his works, often in series, which reveal the strong influence of painting on his art: from a dazzling white he would sometimes claim to have discovered in the light of the Mediterranean to a glowing polychromy, in which chance prevailed over the gesture just as the unexpected prevailed over the planned, an entirely new aspect of painting emerged. As his painting became more material in form, it acquired volume, a magma boiling with precious, abysmal sensuality that abolished the historical sacredness of its illusionistic surface. In 1996 an exhibition at the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo ended up comparing his work with the Van Gogh collection on display; never before or again, as on this occasion, will his art reach out in its generous solipsism to approach another great artist who had also based his own existence on his painting, rain or shine.

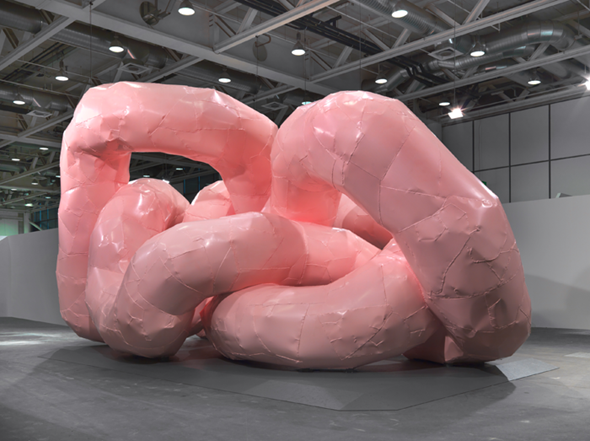

Installation consisting of 43 artworks by Franz West and assistants, artist-friends and colleagues

Exhibition view 54. Biennale di Venezia, 2011

Photo: Stefan Altenburger

»Vom Nutzen (Das Nützen)«, Galerie Bärbel Grässlin, Frankfurt a. M. 2010

Photos: Wolfgang Günzel, Offenbach a. M.

Photos: Wolfgang Günzel, Offenbach a. M.

In 1992, on the occasion of documenta 9, he created the Diwane the first of several works that still enjoy widespread success in various configurations. It is a series of three-seat sofas (the key concept is overcoming the one-to-one relationship to make room for the odd man out – the witness, the other, the in-between) initially consisting of an iron frame partially upholstered, on top of which an old, Oriental-style carpet had been thrown. The work was placed in the courtyard of a former school, which became an outdoor screening venue on some evenings during the hundred-day duration of the exhibition. This was something between Freud’s couch, on which the patient would lie during the psychoanalytic session in order to allow his memories, dreams and obsessions to run free, and the Ottoman sofa that, between the 18th and early 19th centuries, penetrated the world of European furniture, evoking the exhausted and torpid nature of Eastern laxity, as if to counterbalance the intellectual and puritan scepticism of the Enlightenment as well as the criticism of the time.

In that hot summer of 1986 at Sonsbeek, Saskia Bos brought together for the first time a large number of the artists who were leaving their mark on the 80s1 and who had made occasional appearances in major exhibitions over the past few years, thanks to such careful curators such as Kasper König and Jan Hoet. When Denys Zacharopoulos and myself were co-opted by Jan Hoet to direct documenta 9 in 1992, we invited all of them, although some did not participate for various reasons. At the very centre of the commercial and media boom of the most trivial and aggressive forms of Neo-Expressionism then raging throughout the Western world, they represented the last generation of the model of art which started in Europe between the second half of the 12th and the beginning of the 14th centuries, in conjunction with the rebirth of towns and the development of large-scale trade and commerce after the long and dark period of the Middle Ages. That was an evolutionary and progressive model, as well as an expansive one, which beginning in the mid-19th century, alongside colonial imperialism, would spread around the world and eclipse all other models, however illustrious. In its progressive evolutionary phases, which allowed for no point of return, the main hallmarks were the individual as the leading character of his own story, the convergence between nature and culture, the discontinuous analogy between the space of art and that of life, the confluence of ethics and aesthetics into artistic practice, and the absolute capacity of art to not only reveal and thus represent but also to measure and therefore to control the world in all its developments. According to such a model, art became emancipated from any economic, political and spiritual subordination and became rather an instrument of knowledge and of relationships in regard to the world and human life, equal to religion and science in this regard and yet independent from them. This model was substantiated from time to time by a resurgent sense of striving towards a destiny of emancipation and liberation from any of the boundaries and contradictions affecting individual and collective existence.

This generation, to which West rightfully belonged, was the last one to move forward in step with the particular model that, after its domination of the planet, which was completed between World War II and the end of the 1950s, and after another three decades of absolute and positive improvement, plunged into crisis. What followed over the course of the 90s were in fact the last sparks of a long and glorious season which had drawn to its inevitable conclusion: the liberating emphasis of aesthetics was replaced by the extreme exaltation of the sensational, the post-human condition succeeded humanism, and the splendour of the sublime gave way to the triviality of the spectacular. The generation of Franz and his peers deserves credit for restoring the central role of the artwork itself, which had previously been marginalized by avant-garde movements. However, this regained centrality implied the existence of a void, which the artwork was to occupy and, in the process, give shape to. Inside this sublime void, the work rested on the tightrope of desire – »un désir sans nom« (a desire without a name – Jean- François Lyotard) – which linked the solitude of the Self with an acknowledgement of the legitimate existence of the Other, together with the aspiration of returned acknowledgement and, foremost of all, of being loved in the end. Throughout his work, the artist has asserted his own sovereign singularity: far from being a redeeming, elite hero, he is more of a sovereign who is clearly aware of belonging to history and tradition, bearing its weight and responsibility. He is no longer a master transmitting knowledge but is rather primus inter pares (first among equals) in front of his own work: he has posed more than created. He feels himself as a member of a minority that takes great care not to become the majority, imbued with the sense of humour possessed by all minorities while also being pierced by the melancholy that accompanies any form of awareness. In the practice of his art, he has made it his intention to feel the world rather than impress his mark upon it. This is essentially what Franz is about, and it is not by chance that he chose West as his artist’s name.

In that hot summer of 1986 at Sonsbeek, Saskia Bos brought together for the first time a large number of the artists who were leaving their mark on the 80s1 and who had made occasional appearances in major exhibitions over the past few years, thanks to such careful curators such as Kasper König and Jan Hoet. When Denys Zacharopoulos and myself were co-opted by Jan Hoet to direct documenta 9 in 1992, we invited all of them, although some did not participate for various reasons. At the very centre of the commercial and media boom of the most trivial and aggressive forms of Neo-Expressionism then raging throughout the Western world, they represented the last generation of the model of art which started in Europe between the second half of the 12th and the beginning of the 14th centuries, in conjunction with the rebirth of towns and the development of large-scale trade and commerce after the long and dark period of the Middle Ages. That was an evolutionary and progressive model, as well as an expansive one, which beginning in the mid-19th century, alongside colonial imperialism, would spread around the world and eclipse all other models, however illustrious. In its progressive evolutionary phases, which allowed for no point of return, the main hallmarks were the individual as the leading character of his own story, the convergence between nature and culture, the discontinuous analogy between the space of art and that of life, the confluence of ethics and aesthetics into artistic practice, and the absolute capacity of art to not only reveal and thus represent but also to measure and therefore to control the world in all its developments. According to such a model, art became emancipated from any economic, political and spiritual subordination and became rather an instrument of knowledge and of relationships in regard to the world and human life, equal to religion and science in this regard and yet independent from them. This model was substantiated from time to time by a resurgent sense of striving towards a destiny of emancipation and liberation from any of the boundaries and contradictions affecting individual and collective existence.

This generation, to which West rightfully belonged, was the last one to move forward in step with the particular model that, after its domination of the planet, which was completed between World War II and the end of the 1950s, and after another three decades of absolute and positive improvement, plunged into crisis. What followed over the course of the 90s were in fact the last sparks of a long and glorious season which had drawn to its inevitable conclusion: the liberating emphasis of aesthetics was replaced by the extreme exaltation of the sensational, the post-human condition succeeded humanism, and the splendour of the sublime gave way to the triviality of the spectacular. The generation of Franz and his peers deserves credit for restoring the central role of the artwork itself, which had previously been marginalized by avant-garde movements. However, this regained centrality implied the existence of a void, which the artwork was to occupy and, in the process, give shape to. Inside this sublime void, the work rested on the tightrope of desire – »un désir sans nom« (a desire without a name – Jean- François Lyotard) – which linked the solitude of the Self with an acknowledgement of the legitimate existence of the Other, together with the aspiration of returned acknowledgement and, foremost of all, of being loved in the end. Throughout his work, the artist has asserted his own sovereign singularity: far from being a redeeming, elite hero, he is more of a sovereign who is clearly aware of belonging to history and tradition, bearing its weight and responsibility. He is no longer a master transmitting knowledge but is rather primus inter pares (first among equals) in front of his own work: he has posed more than created. He feels himself as a member of a minority that takes great care not to become the majority, imbued with the sense of humour possessed by all minorities while also being pierced by the melancholy that accompanies any form of awareness. In the practice of his art, he has made it his intention to feel the world rather than impress his mark upon it. This is essentially what Franz is about, and it is not by chance that he chose West as his artist’s name.

Photo: Amedeo Benestante, 2010, MADRE, Neapel

The son of a coal dealer and a Jewish dentist, who worked from home, Franz grew up in the Karl Marx- Hof, the large social housing community built at the time of the interwar »Red Vienna«, between 1926 and 1930, which provided 1,382 apartments for a population of over 5,000 people. This is also where he had his first studio. A student of Bruno Gironcoli at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, in his formative years he confronted two of the situations that dominated the city’s art scene at the time: on one side, the Wiener Gruppe of Gerhard Rühm and Oswald Wiener, who, nourished by their reading of Ludwig Wittgenstein and fascinated by the aesthetics and poetics of the Baroque, Dada, and Surrealism, had developed a sort of critical scepticism towards contemporary culture on all levels; and, on the other, the intense, spectacular activity of Viennese Actionism, as represented by Hermann Nitsch, Otto Muehl, Günter Brus, and Rudolf Schwarzkogler, whose all-round research of a cathartic palingenesis of the individual and society found expression in extreme orgiastic rituals and practices. Surrounded by the proletarian and petty-bourgeois communities at the Karl Marx-Hof and exposed to the intellectual and behavioural extremes of the most advanced urban culture at that time, as well as to the philistinism of the mainstream, Franz had his own Verwirrungen (confusions), but he also managed to grasp the meaning of that nesnesitelná lehkost bytí (unbearable lightness of being) from which his art and his will to be an artist (kunstwollen) originated.

After overcoming any sense of palingenetic drift and constructive utopia thanks to the healthy scepticism of his positive intelligence, he arrived at the assertion of sovereign singularity that I described above, much like other artists of his generation, while still deriving inspiration from his own unique learning environment. Unlike many of his peers, his striving was so strong and well-nourished as to project him beyond the limits of his initial decade, allowing him to pass unspoilt through the decay of the primacy of Western culture and finally full-steam ahead into a new millennium, where, unexpectedly, he found himself graciously, blissfully, at ease. When the great Western river finally flowed into the ocean of the world at large, which it had previously been polluting, others were scattered by the first tide, whereas Franz’s vessel continued on sailing towards the eternal horizon. A »sublime success« – as the I-Ching, the ancient Chinese book of changes, might describe it.

Translated from the Italian by Loretta Solaroli and Keith Jones

PIER LUIGI TAZZI is an art critic and curator based in Capalle, Tuscany, and Korat, Thailand.

(1) Also participating in Sonsbeek 86, besides Franz West, were the following: Marco Bagnoli, Ettore Spalletti, Anish Kapoor, Thomas Schütte, Reinhard Mucha, Jean-Marc Bustamante (under the name of the group he had formed with Bernard Bazile: Bazilebustamente), Richard Deacon, Lili Dujourie, Fortuyn/O’Brien, Katharina Fritsch, Shirazeh Houshiary, Niek Kemps, Harald Klingelhöller, Jan Vercruysse, and Heimo Zobernig. I would also add Remo Salvadori, who during the second half of the 70s was among the first to demonstrate a similar attitude, and then also Günther Förg, Juan Muñoz, Thierry de Cordier, Thomas Ruff, Cristina Iglesias, Herbert Brandl, Mirosłav Bałka, and, from overseas, Rodney Graham, Robert Gober, Robert Therrien, and Joe Scanlan.

After overcoming any sense of palingenetic drift and constructive utopia thanks to the healthy scepticism of his positive intelligence, he arrived at the assertion of sovereign singularity that I described above, much like other artists of his generation, while still deriving inspiration from his own unique learning environment. Unlike many of his peers, his striving was so strong and well-nourished as to project him beyond the limits of his initial decade, allowing him to pass unspoilt through the decay of the primacy of Western culture and finally full-steam ahead into a new millennium, where, unexpectedly, he found himself graciously, blissfully, at ease. When the great Western river finally flowed into the ocean of the world at large, which it had previously been polluting, others were scattered by the first tide, whereas Franz’s vessel continued on sailing towards the eternal horizon. A »sublime success« – as the I-Ching, the ancient Chinese book of changes, might describe it.

Translated from the Italian by Loretta Solaroli and Keith Jones

PIER LUIGI TAZZI is an art critic and curator based in Capalle, Tuscany, and Korat, Thailand.

(1) Also participating in Sonsbeek 86, besides Franz West, were the following: Marco Bagnoli, Ettore Spalletti, Anish Kapoor, Thomas Schütte, Reinhard Mucha, Jean-Marc Bustamante (under the name of the group he had formed with Bernard Bazile: Bazilebustamente), Richard Deacon, Lili Dujourie, Fortuyn/O’Brien, Katharina Fritsch, Shirazeh Houshiary, Niek Kemps, Harald Klingelhöller, Jan Vercruysse, and Heimo Zobernig. I would also add Remo Salvadori, who during the second half of the 70s was among the first to demonstrate a similar attitude, and then also Günther Förg, Juan Muñoz, Thierry de Cordier, Thomas Ruff, Cristina Iglesias, Herbert Brandl, Mirosłav Bałka, and, from overseas, Rodney Graham, Robert Gober, Robert Therrien, and Joe Scanlan.

Stefan Ratibor

I first met Franz West over thirteen years ago in the studio that he had at the time in the Annagasse in Vienna. Shortly after we met, Franz asked me to accompany him on a trip to Columbia University in New York, where we joined art studios and he gave a lecture. At the beginning of the lecture, he asked me to sit with him onstage and, after the introduction from the head of the department, presented me as his translator, a task for which I was totally unprepared. He spoke for twenty minutes without a break and then joined the audience in watching me muddle through a poorly worded translation; afterwards, he thanked me profusely.

Over the years, Franz also allowed me, among other things, to manage a conversation with Sarah Lucas via text message, his preferred method of communication; to publish, in newspaper format, extracts from books he was reading while working on a certain group of sculptures; and to walk alongside him – for all of this I shall forever remain grateful.

Franz West was one of the most original artists in postwar Europe, a remarkable thinker and a deeply kind human being. His influence on younger artists was extraordinary, as were his friendships with them and with his contemporaries. Both groups were intrinsic to his studio practice, the many group shows he took part in and the frequent collaborations he undertook. This unique openness to and engagement with other artists’ visions is best understood by recalling a project he organized at the time of the Venice Biennial in 2007, The Hamster Wheel. It was not part of the actual Biennial, for which he had contributed a major work in the Arsenale, but it stood tantalizingly close – across the water at the Fondamente Nuovissima. Franz had simply rented a building and invited artist friends to send works there so as to take part in this uncurated and purely artist-driven project.

The dialogues he enjoyed with others – from writers to philosophers, designers, musicians and dancers – reflected his wider intellectual vision. These collaborations influenced his extraordinary sculptural work. His collages, his furniture and his writings made him the unusually all-around artist and true Renaissance man that he was. Only Vienna could have produced such an artist: an heir of the Wiener Werkstätte and Jugendstil, a student of Freud and Wittgenstein, a witness of Actionism and also the product of the many political and social strands of the Central European maelstrom of postwar Vienna. That being said, he was never nostalgic or sentimental but always entirely modern and curious.

Franz was consistently humble and modest. I shall miss his laughter and humour, his incomparable text messages and jokes, his resolute kindness and his total artistic integrity.

Vienna feels much less original, brilliant and fun this summer.

STEFAN RATIBOR is Director of Gagosian London.

Piazza di Pietra, Rom, Photo: Matteo Piazza (Courtesy Gagosian Gallery)

Photo: Costas Picadas

Courtesy Galerie Meyer Kainer, Photo: Stefan Altenburger