Hans-Peter Feldmann

Bawag Contemporary, Vienna 21.6.–26.8.2012

© O.O.; VBK Vienna

© O.O.; VBK Vienna

Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York

© O.O.; VBK Vienna

Slavs and Tatars »Beyonsense«

MoMA Projects Gallery, New York, 15.8.–10.12.2012

»POLITICAL«, HE SAYS

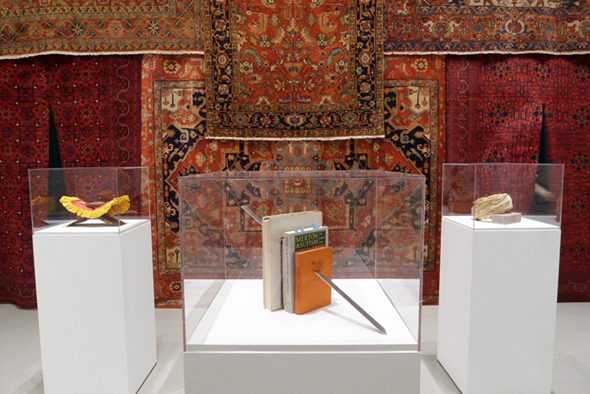

I’m situated in front of a massive embroidered map by Alighiero Boetti on MoMA’s second floor searching for the Projects Gallery where Slavs and Tatars’ first United States solo exhibition, Beyonsense, is opening. On my way to the gallery, I pass Jeff Koons’s Three Ball 50/50 Tank (Two Dr. J Silver Series, One Wilson Supershot), 1985. I circle the tank and just gawk at it, perhaps seriously considering Jeff Koons for the first time. Passing through Dieter Roth’s large installation of 131 Toshiba monitors, Solo Scenes, 1997–98, I’m reminded of the perverse video surveillance activity of William Baldwin’s character in the paranoid erotic thriller Sliver. In Roth’s case, the artist turned the camera on himself in a kind of sad auto-voyeurism, but as the trailer for Sliver states, »The view from the outside is nothing compared to the view inside.« Eventually I enter the Slavs and Tatars installation, where I encounter a variety of glass-encased curios set on pedestals. On one, five books standing upright have been pierced through diagonally by a dagger. On another, a wheat turban. On a third, an African cucumber carved from wood and bearing the phrase »the dear for the dear« in black ink.

I first discovered the work of Slavs and Tatars, a collective of artists who reside in, travel throughout, and investigate the cultures of Eurasia, at the West Coast debut of their book Kidnapping Mountains (2009) hosted by Ooga Booga in Los Angeles. There, I had the chance to view a selection of the group’s unique printed matter. I found their large sculpture PrayWay, featuring blue fluorescent light, to be a highlight of the 2012 New Museum Triennial, The Ungovernables. Always curious about lands and cultures with which I’m unfamiliar, I was encouraged to seek another opportunity to bathe in the collective’s fashionable multiculturalism. Thumbing through one of their artist’s books in the Beyonsense reading room, I come across a Malagasy proverb: »Foreigners are not people but gods without a place in heaven.« Like a foreigner, I then move through a partition of carpets hung floor-to-ceiling and enter a mystical, softly lit installation. Behind the carpets I discover a small fountain spurting a blood-red liquid that splatters onto a platform finished with white square tiles. Rings of arms, interlocking hands, and characters from three regional scripts have been painted onto the tiles. The room is aglow from the yellow-green fluorescent lights that form a pyramid-shaped canopy suspended over the fountain. This element is inspired by a Dan Flavin piece designed for a New York mosque. Lavender incandescent bulbs have been affixed beneath the padded benches that run along two walls of the installation. A sampling of the collective’s artist’s books, wherein one can get a sense of the group’s linguistic and cultural associations, are set atop the brilliantly patterned benches.

I lounge in the reading room for a while and look at a large mirror painting that reads »Mother Tongues & Father Throats«. It’s propped against the wall next to another of equal dimensions depicting a big, pink, open mouth. Later, I ask a friend what he thinks of the collective’s motivation. »Political«, he says. Yet the work of Slavs and Tatars appears too coolly intellectual and carefully designed to arouse an efficacious reaction. Their work is attractive precisely because it isn’t conceptually or theoretically demanding. Its graphical and aesthetically distinct set of references and symbols remain compelling with or without tactile immersion in the history of Eurasia.

JON LEON

I’m situated in front of a massive embroidered map by Alighiero Boetti on MoMA’s second floor searching for the Projects Gallery where Slavs and Tatars’ first United States solo exhibition, Beyonsense, is opening. On my way to the gallery, I pass Jeff Koons’s Three Ball 50/50 Tank (Two Dr. J Silver Series, One Wilson Supershot), 1985. I circle the tank and just gawk at it, perhaps seriously considering Jeff Koons for the first time. Passing through Dieter Roth’s large installation of 131 Toshiba monitors, Solo Scenes, 1997–98, I’m reminded of the perverse video surveillance activity of William Baldwin’s character in the paranoid erotic thriller Sliver. In Roth’s case, the artist turned the camera on himself in a kind of sad auto-voyeurism, but as the trailer for Sliver states, »The view from the outside is nothing compared to the view inside.« Eventually I enter the Slavs and Tatars installation, where I encounter a variety of glass-encased curios set on pedestals. On one, five books standing upright have been pierced through diagonally by a dagger. On another, a wheat turban. On a third, an African cucumber carved from wood and bearing the phrase »the dear for the dear« in black ink.

I first discovered the work of Slavs and Tatars, a collective of artists who reside in, travel throughout, and investigate the cultures of Eurasia, at the West Coast debut of their book Kidnapping Mountains (2009) hosted by Ooga Booga in Los Angeles. There, I had the chance to view a selection of the group’s unique printed matter. I found their large sculpture PrayWay, featuring blue fluorescent light, to be a highlight of the 2012 New Museum Triennial, The Ungovernables. Always curious about lands and cultures with which I’m unfamiliar, I was encouraged to seek another opportunity to bathe in the collective’s fashionable multiculturalism. Thumbing through one of their artist’s books in the Beyonsense reading room, I come across a Malagasy proverb: »Foreigners are not people but gods without a place in heaven.« Like a foreigner, I then move through a partition of carpets hung floor-to-ceiling and enter a mystical, softly lit installation. Behind the carpets I discover a small fountain spurting a blood-red liquid that splatters onto a platform finished with white square tiles. Rings of arms, interlocking hands, and characters from three regional scripts have been painted onto the tiles. The room is aglow from the yellow-green fluorescent lights that form a pyramid-shaped canopy suspended over the fountain. This element is inspired by a Dan Flavin piece designed for a New York mosque. Lavender incandescent bulbs have been affixed beneath the padded benches that run along two walls of the installation. A sampling of the collective’s artist’s books, wherein one can get a sense of the group’s linguistic and cultural associations, are set atop the brilliantly patterned benches.

I lounge in the reading room for a while and look at a large mirror painting that reads »Mother Tongues & Father Throats«. It’s propped against the wall next to another of equal dimensions depicting a big, pink, open mouth. Later, I ask a friend what he thinks of the collective’s motivation. »Political«, he says. Yet the work of Slavs and Tatars appears too coolly intellectual and carefully designed to arouse an efficacious reaction. Their work is attractive precisely because it isn’t conceptually or theoretically demanding. Its graphical and aesthetically distinct set of references and symbols remain compelling with or without tactile immersion in the history of Eurasia.

JON LEON

Photo: Courtesy of the artists

Silbergelatineabzug, 51 x 77 cm

Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg (c) Zanele Muholi

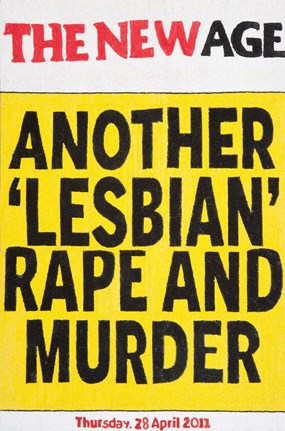

QUEERCIDE

On 20 April 2012 the apartment of the South African artist and activist Zanele Muholi (*1972) was broken into. What looked like a normal burglary was most likely a targeted action to destroy documents. For the main losses were more than twenty hard disks, four years of work, files and films in which Muholi had tried to document and make visible the lives of, and the violence against, LGTBI (Lesbian, Gay, Transgender, Bisexual, Intersex) people.

The wide-ranging and far from »innocent« material was intended for an exhibition in July at the South African Stevenson Gallery in Capetown, but now nothing could come of that. Muholi had to re-design the exhibition or, to be precise, figure out how to realise it with the remaining material. The result was a sketchy show using various media and approaches to publicise the (at-risk) lives of LGTBI. At the centre were »hate crimes«, especially »corrective rapes«, which, even today, many people in South Africa still believe can turn lesbians into heteros – and which the state does all too little to oppose. Thus, on the first wall of the exhibition is a list commemorating more than twenty hate murders of this kind. Muholi had documented many of these acts of violence in detail, and that seems to have been precisely the burglars’ target. Surrounding the list, the artist has marked out the theme with posters, photos and films, but some of these things have been implemented in a way that is not yet fully matured and too sketchy. The film @24 (2012) documents the funerals of Thapelo Makutle and Noxolo Nogwaza, both of whom were murdered at the age of twenty-four. Viewers sit in a room furnished like a traditional room of mourning in the townships. That could seem sentimental, but it is primarily a minimal contextualisation of hard facts, as if the purpose were to avoid exposing the film to the pathos or indifference of the white cube. The courage, the strength and the discipline displayed by Muholi in performing her struggle and which also characterise her best works are especially clear in the third room of the exhibition. On its walls hang roughly one hundred black-and-white portraits of black women who have come out as lesbians and who pose standing upright and looking directly into the camera – and who risk their lives by doing so. Each of the women portrayed had to sign a document saying that she agreed to being photographed and to having the photograph published, because these portraits could make them targets of »corrective rapes« and extensive discrimination.

On 20 April 2012 the apartment of the South African artist and activist Zanele Muholi (*1972) was broken into. What looked like a normal burglary was most likely a targeted action to destroy documents. For the main losses were more than twenty hard disks, four years of work, files and films in which Muholi had tried to document and make visible the lives of, and the violence against, LGTBI (Lesbian, Gay, Transgender, Bisexual, Intersex) people.

The wide-ranging and far from »innocent« material was intended for an exhibition in July at the South African Stevenson Gallery in Capetown, but now nothing could come of that. Muholi had to re-design the exhibition or, to be precise, figure out how to realise it with the remaining material. The result was a sketchy show using various media and approaches to publicise the (at-risk) lives of LGTBI. At the centre were »hate crimes«, especially »corrective rapes«, which, even today, many people in South Africa still believe can turn lesbians into heteros – and which the state does all too little to oppose. Thus, on the first wall of the exhibition is a list commemorating more than twenty hate murders of this kind. Muholi had documented many of these acts of violence in detail, and that seems to have been precisely the burglars’ target. Surrounding the list, the artist has marked out the theme with posters, photos and films, but some of these things have been implemented in a way that is not yet fully matured and too sketchy. The film @24 (2012) documents the funerals of Thapelo Makutle and Noxolo Nogwaza, both of whom were murdered at the age of twenty-four. Viewers sit in a room furnished like a traditional room of mourning in the townships. That could seem sentimental, but it is primarily a minimal contextualisation of hard facts, as if the purpose were to avoid exposing the film to the pathos or indifference of the white cube. The courage, the strength and the discipline displayed by Muholi in performing her struggle and which also characterise her best works are especially clear in the third room of the exhibition. On its walls hang roughly one hundred black-and-white portraits of black women who have come out as lesbians and who pose standing upright and looking directly into the camera – and who risk their lives by doing so. Each of the women portrayed had to sign a document saying that she agreed to being photographed and to having the photograph published, because these portraits could make them targets of »corrective rapes« and extensive discrimination.

Zanele Muholi, Crime Scene #1–#4, 2012

C-Prints, 33 x 50 cm

Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

(c) Zanele Muholi, Photo: Antoine Tempé

C-Prints, 33 x 50 cm

Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

(c) Zanele Muholi, Photo: Antoine Tempé

But if you are now thinking that South Africa is backward and sexist, you are mistaken. Same-sex marriage has been legal since 2007, and currently on view at the Museum Africa in Johannesburg is the exhibition Johannesburg Tracks: Mapping sexuality in the city, which displays the everyday lives of LGTBI in the city. The fact is that the history and society of South Africa are the result of extraordinary tensions and conflicts that exist still today. On the wall opposite the portraits are quotations written by hand in which the women report their humiliating experiences – for these seemingly classic and apparently timeless portraits spring from the toughest reality. One room further Muholi brings this tension to a point while simultaneously extending it. There you can see the documentary film Difficult Love (2011), a 45-minute self-portrait by Muholi that has won awards at several festivals. The film, however, is not an exercise in self-presentation but a reflection based on reality and personal experience of the »black lesbian woman photographer« (Muholi describing herself) in relation to class, gender, race and oppression.

Standing before some young people in the film, Muholi says, apparently without warning: »Beauty is all I want to see«. This very question of seeing and being seen, on which beauty is based, stands at the centre of her work and is a political act: Muholi practices rigorously formal visibility as dissidence, enlightenment and hope. For, seeing and being seen have always been the core task of art, and it is for this very reason that political activism and art combine with rare conviction in Muholi’s case. This is also why a small flat screen monitor hangs opposite Difficult Love, casually showing a lesbian porn film that is just under four minutes long, a sex act in close-up of moving bodies and fingers, filmed by Muholi. A female colleague said that here the filmmaker and the editor have submitted to eroticism too readily. She was not wrong, but the audacity with which the politically committed documentary and the DIY sex film are juxtaposed is beautifully and unabashedly disturbing.

DANIEL BAUMANN

Translated by Nelson Wattie

Standing before some young people in the film, Muholi says, apparently without warning: »Beauty is all I want to see«. This very question of seeing and being seen, on which beauty is based, stands at the centre of her work and is a political act: Muholi practices rigorously formal visibility as dissidence, enlightenment and hope. For, seeing and being seen have always been the core task of art, and it is for this very reason that political activism and art combine with rare conviction in Muholi’s case. This is also why a small flat screen monitor hangs opposite Difficult Love, casually showing a lesbian porn film that is just under four minutes long, a sex act in close-up of moving bodies and fingers, filmed by Muholi. A female colleague said that here the filmmaker and the editor have submitted to eroticism too readily. She was not wrong, but the audacity with which the politically committed documentary and the DIY sex film are juxtaposed is beautifully and unabashedly disturbing.

DANIEL BAUMANN

Translated by Nelson Wattie

Beads, glue, wooden panel

117 x 77 cm