In the 1960s, LEE LOZANO (1930-1999) counted amongst the central figures of New York’s art scene. Her versatile painterly and graphic œuvre ranges from satirically sexualised “tool” paintings, abstract Op Art paintings to reflections on painting as medium in the form of perforated canvases. By the end of the 1960s, she was combining in her conceptual “pieces” both art and life in ever more radical ways, only to withdraw entirely from the art business with her Dropout Piece in 1970/71. Since her death in 1999, the art world has brought her vividly into memory; most recently through a major retrospective show at the P.S.1. A portrait of the artist by HANS-JÜRGEN HAFNER.

“I will not call myself an art worker but rather an art dreamer and I will participate only in a total revolution that is simultaneously personal and public.” (Lee Lozano, statement given on April 10, 1969)

Seen from a distance of time, the boundaries seem to blur increasingly. Clearly discernible is the frenetic activity in and around the Village; exhibitions being set up at breakneck speed and discussed energetically, all sorts of print matter circulated, letters sent back and forth and telephone calls made. Although the group of actively involved persons seems to be surveyable at a glance, just a small, almost conspiratorial circle of artists and art critics, a handful of art dealers and gallery owners comprise the scene. However, seen from today’s perspective, we can hardly distinguish between the projects, around let’s say 1969, that were then zealously ostracised: projects related to Minimal Art, Land Art and, of course, Concept Art that was contributing fine nuances, whose parameters and profile was expanding the horizons of the art of the time. And the greater the radical fervour with which current art practices exposed its formal and thematic content the more subtle was the discrimination against them from the art world. “Art as Idea” now replaced painting and sculpture, manifesting itself either at the edge of visibility – sometimes – through texts, or otherwise in preset situations and test arrangements, often even without an audience. De-materialisation” was the magic key word that Lucy Lippard, artist and art critic, the theoretical mastermind of the down-town scene, had coined and with which she legitimised the new practices in art as manifestations critical of the art market. But although Lippard distances herself from a painting-fixated official art scene, she also gets entangled in the modernist theory which claims that art is a constantly self-improving process.

Nevertheless, the appearance of art and the conditions of perception attending it underwent a lasting change: photographs, and soon also early videos, only trigger the memory, they are not the “work” itself but merely a “document”; they bear witness to actions, to interventions and processes. And while in the eyes of its critics the new art progressively became a question of conviction, many artists were very specifically concerned with socio-political topics. The Art Workers Coalition, for instance, in addition to generally improving the working conditions for the artist, also promoted the minority quota in the exhibition scene. But while doyens like Sol LeWitt were committed to more modern museum policies, Lee Lozano argued for an entirely different programme. At a hearing of the Coalition on April 10, 1969, she introduced herself as an “art dreamer”, quite counter to the then current popular image of “culture worker” and, with a sweeping gesture, called for an all-encompassing “art revolution”. More precisely, she stood for a “total personal & public revolution”.1

„I will not seek fame, publicity or suckcess.“ (Lee Lozano, September 8, 1971)

Lee Lozano, actually Lenore Knaster (1930-1999), had sunk into oblivion for a very long time. As an artist she had completely vanished from the turbulent art scene as early as [in ]the 1970s, even though she was well established and had good prospects in art. Apart from exhibitions in Cologne, Halifax and London, she even got a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum, not forgetting the regular and very positive critiques. “E”, as she was called, withdrew inside herself completely and her Joey-Ramone-look was all that remained of her “scene” image. In the following years, she lived under extremely penurious conditions, mainly in Dallas, which is where she died at the end of October 1999. And although Lucy Lippard called her “the major female figure” in New York’s art world of the 1960s2in a feminist review of Concept Art, a befitting tribute to Lozano’s work still needs to be made and her place within the multitude of conceptual positions in art clarified. Since 1998, there is a remarkable flux of heterogeneous symptoms for a reawakened interest in the complex and obscure figure and the work of “Lozano”.3 Developed over more than ten years, this body of work seems as versatile and inspiring as it is disparate and difficult. In real fact this “rediscovery” of the artist in 1998 started with a tour de force: her work was shown simultaneously at three New York galleries as well as in a retrospective show at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut. All these projects focused on specific work groups from Lozano’s oeuvre, particularly on the multifaceted painterly work in which her early figurations (Early 60s and bombastic Tool Paintings) present a contrast to a sophisticated and beautiful Minimalism. The show at Hartford proves to be the most fruitful and lasting for this reappreciation of her art. For the first time, Lee Lozano’s painterly chef d’oeuvre, the Wave Series (1967-70), was presented in combination with texts and excerpts from her notes and diaries, shifting the viewer’s attention to entirely different facets of her artistic project.

„I have started to document everything because I cannot give up my love of ideas.“ (Lee Lozano, February 3, 1968)

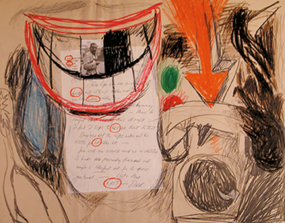

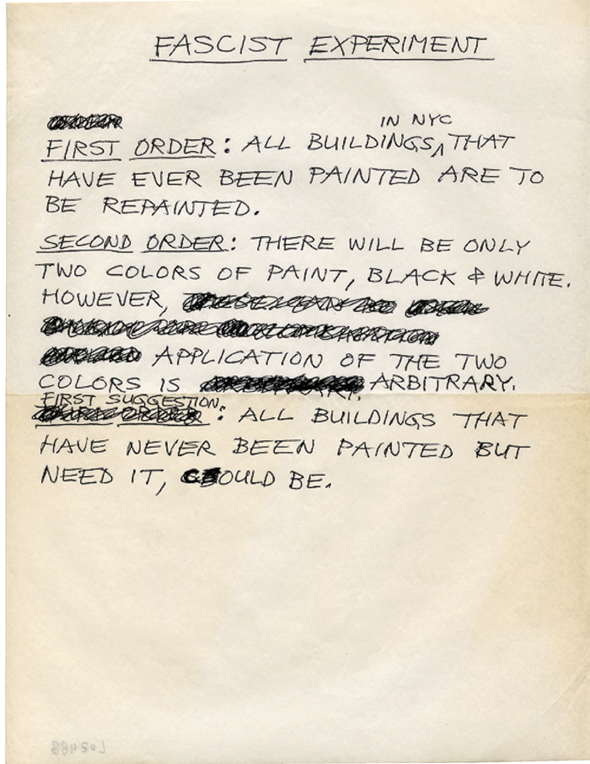

These painstaking notes provide an exhaustive and panoramic view of art and life. Lozano not only accompanies her painting with precise sketches, memos and protocols of her ideas, she even goes as far as to make biography become gradually congruent with art. Lozano turns her everyday life into an aesthetic principle, making drawings in her diary to record the effects of her experiments, for instance, the effects on painting of consuming “pot” for several weeks at a stretch. The partially performative and partially ascetic investigations of her own condition (becoming stoned before painting, masturbating, etc.) are juxtaposed against precisely calculated social situations, for example, when she – as if anticipating the popular interaction models of the 1990s – takes money from a marmalade jar and offers it “for free” to the bewildered spectator. The entries in her diary serve Lozano as material for the Language Pieces. Painstakingly written by hand, these texts even assume the status of drawing, as she explains in her Clarification Piece of July 28, 1969.

Such indexical text sheets that were normally performative in nature were undoubtedly en vogue at the time and were conceived for exhibitions, often also for publication and circulation in catalogues or fanzines. In particular, hardcore conceptualists like Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth and Lawrence Wiener produced such works, and Wiener’s “statements” have since then become icons of Concept Art. In Lozano’s case, however, the word concept also had an existential aftertaste. Indeed, our reading of the many sediments of meaning in the Language Pieces can be said to oscillate between atmospheric, historical and sociological connotations or art gossip and notation, they convey the artist’s voice, a stringent conceptual planning and appear amazingly three-dimensional. It seems that Lozano always had the potential reader in mind, acting as if before a running camera. This leads to several interesting parallels – on the one hand, to Vito Acconci’s obsessive video documentations of himself and, on the other, to Lee Lozano’s spiritual exercises which became independent forms of the everyday at the same time as Adrian Piper’s isolated Kant reading, Food for the Spirit, which was accompanied by photographic self-portraits made as a kind of “reality check”.

In April 21 1969, Lozano began a series of dialogues, which lasted several months, as part of her Dialogue Pieces4 involving especially such artists as Robert “Moose” Morris, James Lee Byars, Dan Graham, Ian Wilson5 or Bob “Smitty” Smithson, as well as gallery owners (Rolf Ricke, who gave her a solo show in his gallery in Cologne), curators (Marcia Tucker) or even her own mother. Lozano’s protocol-like notes read like a who’s who list of the downtown scene. Moreover, they are recordings in which, in addition to her personal assessments of the individual conversations – mostly held in Lozano’s own flat, and very seldom on the phone – she took down very precise notes about the formal aspects of her “pieces”. As she says, “The purpose of this piece is to have a dialogue with as many people as possible, not to make a piece.” Contrary to many of the Concept Art works which had become merely self-relevant long ago, Lee Lozano, who wanted to tie art and life very closely together ultimately made them overlap in a manner that remains disturbing until this day.

„The series before it is sold must be shown as a set and at a ‚reputabale‘ place with good space in New York City.“ (Point 5 from Lozano’s Fantasy, February 9, 1969)

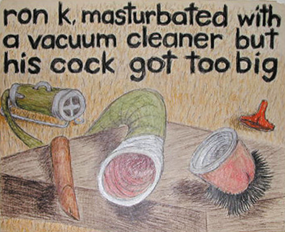

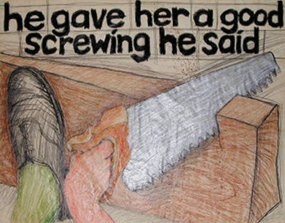

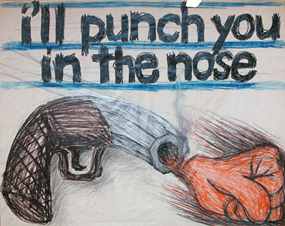

Alongside her social as well as everyday life-regulating performance experiments, Lee Lozano also continued to work on her paintings. In 1967 she began to study at the Art Institute Chicago, where she developed a crudely figurative cartoonish style in painting and drawing. Her early cartoons are often illustrated puns such as “cock in the pocket” and are offensively sexual. Tools and symbols of genitals or grotesquely grinning masks collide with slogans written boldly cross the page. The quality of these sheets is rarely outstanding. Despite the appearances of Outsider Art or Art Brut, Lee Lozano plays out her basic theme in ever different variations. Repetition makes even the most wildly aggressive gestures seem systematised and her Tool Paintings come across as even more unswerving. These obsessive repetitions of hammer and gripper compositions seem as if pushed with great effort into the considerably large canvases. But despite their immediate and immense painterly impact, they were preceded by numerous sketches and drafts.

In 1964 Lozano changed her style totally. It was perhaps because of a very reception-oriented method of work that she gave up self expression in favour of stylised mechanistic subjects and compressed surfaces. At any rate, it seems as if decisions had been made regarding her position since Pop Art is as close at hand as a turn to Minimalism. The affinity to Pop Art in her works until 1964 could also be seen as an anticipation of Philip Guston’s departure from abstraction in the form of “impure” style.

At all events, “system” became increasingly the object and the method of production in Lozano’s paintings. Following an economy in colour, Constructivist three-dimensionality as in Ream or Slide, she spent the next three years making the Wave Series. The “waves” are based on reflections on physics, and her preliminary mathematical experiments culminated in a rigid production plan: once the composition was determined, the canvases (often completed within three days!) were made in a single and non-stop performative act of painting. The results were often just as majestically opaque as seductively iridescent. Leaning against the wall as a series in a room painted black and with dramatic lighting – as installations in a specific sense – they more than ever before desired to be experienced rather than just looked at.

„Can’t think, can’t write, can’t draw.“ (Lee Lozano, from a sketch of September 9, 1970)

Writing about Lee Lozano always has certain pathographic features since her work and biography can be barely separated from each other. As early as in February 1969, altogether different, partially contradictory elements in Lozano’s lifestyle and work came to a climax. In the Withdrawal Piece, which led to Strike Piece, commenced her slow, luxuriously staged withdrawal – from the art scene to begin with.

At what point her art took over life and led to Lozano’s “decline” cannot be determined. Her resistance to the art environment kept growing and in 1971, Lozano started boycotting all communication with other women, initially only for a limited period of time to begin with. Shortly thereafter, she left New York. Her exercise in performance had now become earnest. Lozano was never to speak with any women again.

Translated by Nita Tandon

HANS-JÜRGEN HAFNER is author and critic of contemporary art and music. He lives in Nuremberg.

LEE LOZANO was born in 1930 as Lenore Knaster in Newark, New Jersey. From 1948-51 she studied philosophy and natural sciences at the University of Chicago, finishing with a B. A. During 1952-56, Lozano was employed by the Container Corp. of America. In 1956, she married the designer and architect Adrian Lozano. From 1957-59, she studied art at the Art Institute of Chicago. This was followed by an extensive trip to Europe and divorce from Adrian Lozano in 1960 and her relocation to New York. In 1971, Lozano terminated her art activities, moved away from New York and for ten years was believed to have disappeared. In 1982, she moved to live with her parents in Dallas, where she died in 1999.

THE ESTATE OF LEE LOZANO/Hauser Wirth, Zurich, London, New York