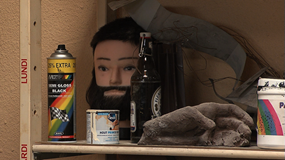

Still from »Das Loch (The Hole)«, 2010

All images: Courtesy of the artists and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi

All images: Courtesy of the artists and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi

All Is Disquiet

If you listen to the silence, and keep your eyes on the stillness, you might just catch what's hiding inside the videos of the Belgian artists JOS DE GRUYTER und HARALD THYS. By JENNIFER KRASINSKI

For 20-odd years, Belgian artists Jos De Gruyter and Harald Thys have created a body of 21 video works possessed of the darkly divided spirit of collaboration, their peculiar productions being those of artists acting not only in consort with one another, but also with the hidden forces occupying the territories (both physical and psychological) in which their haunting narratives take place.

Site readings illuminate their realm: sparse, constructed spaces that sometimes look like stages, at other times, fall-out shelters for deflated characters who always seem to be post-something: -trauma, -language, -human. The stories stutter along, stunted hybrids of eviscerated fairy tales and exhausted melodramas. The actors – untrained, and largely drawn from the artists’ circles of family and friends – do not perform so much as gesture and pose in a style so stripped of theatrics it could be mistaken for a list of symptoms: unmoving, unspeaking, punctured, perverse. (Imagine Bresson’s mannequins rendered spiritless, or Herzog’s hypnotized cast of Heart of Glass relieved of panic’s propeller). On top of that, the artists film their numbskulls in sheer stupidity – in transparent veils of formal dumbness that rightly refuse classic cinematic modes of storytelling. (After all, doesn’t inaction inherently resist the relevance of coverage, continuity, and cutting?) Divested of the usual seductions, the disquieting world of De Gruyter and Thys seems to lay the groundwork for a particular kind of insurrection, one that rebuffs certain standards and practices of art-making in order to return our attentions to the subversive powers of the artist.

Having met in 1987 as disgruntled film/video students at the Sint-Lukas Brussels University College of Art and Design, De Gruyter and Thys began their collaboration with a 5-minute middle finger-wagger titled Mime in the Videostudio (1988). The video stars a young Thys – all gangly limbs in a white vest and underwear – imitating gymnastic exercises to hokey Europop songs in the school’s video studio. He marches, pretends to swim, and performs graceless acrobatics, anemic goose steps, and stiff-legged kicks that are as funny as they are sad sack, his movements reminiscent of the disarming flails of Taylor Mead, Warhol superstar cum court jester. Thys then parades around carrying unidentified objects that belong to the ex-priest who runs the school’s video studio, and who hides his pornography there. The young artist ends his show by enthusiastically mouthing the lyrics to one of the songs (»Big city!/Big, big city!«) out of time with the recording. Bumbling and puckish, Thys performs a kind of failed fascism – of the body, of art education, of religion – as well as a playful, if pointed, interrogation of the space in which art is made.

Still from »Das Loch (The Hole)«, 2010

The intersection of mental state and physical space is terrain that De Gruyter and Thys would later explore via strange and shattered story lines that lay bare the narrative systems on which we have come to rely to produce meaning. In Parallelogram (2000), a domestic (or perhaps more accurately, a domesticating) space frames the psychological tensions between a man and a woman who stare at one another – she while sitting on a couch, he while standing in a corner. No one speaks, perhaps because there is nothing left to be said. In the scenes that follow, the man and two henchmen drag a creature from a cell beneath the floor, head bagged like a prisoner’s. They place the figure behind a large glass window (the titular parallelogram) through which he and the woman share a moment of recognition – perhaps seeing additional parallel lines between them. Whether the creature has been trotted out as entertainment, for companionship, or as a warning is unclear; what is clear is that after confronting it – after sharing the same space with it – the man and the woman are finally brought physically closer together, if driven farther apart emotionally. If De Gruyter and Thys do not define too sharply the narrative details (or the symbolic resonance) of these events, we are in turn more at liberty to explore our own minds and project our own anxieties in order to draw our own conclusions.

The refraction of psychological states through physical spaces almost becomes the literal subject of a subsequent series of videos that form a kind of triptych: Ten Weyngaert (In the Vineyard, 2007), Der Schlamm Von Branst (The Clay from Branst) and The Frigate (both 2008), all of which – in one way or another – question the therapeutic value of art by exploring different places in which it lives. Ten Weyngaert is the name of a community center in Brussels where De Gruyter worked for years. According to the artist, although the center was founded to free its participants’ imaginations through art therapy classes, it tended to have the opposite effect, inspiring malaise and catatonia in the eccentric failures who populated it.

In their video, De Gruyter and Thys’s characters reenact this depressed state inside an institutional community room. Most stare off into space, glassy-eyed and unmoving; two are bullied, one man chokes someone, and yet another twists his face into a manic smile as we listen to a story told in voiceover of a man who squeezes small mice for sexual pleasure, a perversion resulting from a trauma in his youth. We also watch a play within a play put on by the residents; cutting between the community room and a dark, theatrical space lit by a sickly green light, we see our catatonics cast in a variety of awkward roles: a man in blackface, another in yellow face, a scarecrow, magicians. Sadly, their performances do not provide the expected healing, freeing effects expected; everyone seems to erode into further depths of despair and lifelessness. Having a last laugh, De Gruyter and Thys offer the characters the means to truly free themselves: not by making art, but by jumping out of a window.

The refraction of psychological states through physical spaces almost becomes the literal subject of a subsequent series of videos that form a kind of triptych: Ten Weyngaert (In the Vineyard, 2007), Der Schlamm Von Branst (The Clay from Branst) and The Frigate (both 2008), all of which – in one way or another – question the therapeutic value of art by exploring different places in which it lives. Ten Weyngaert is the name of a community center in Brussels where De Gruyter worked for years. According to the artist, although the center was founded to free its participants’ imaginations through art therapy classes, it tended to have the opposite effect, inspiring malaise and catatonia in the eccentric failures who populated it.

In their video, De Gruyter and Thys’s characters reenact this depressed state inside an institutional community room. Most stare off into space, glassy-eyed and unmoving; two are bullied, one man chokes someone, and yet another twists his face into a manic smile as we listen to a story told in voiceover of a man who squeezes small mice for sexual pleasure, a perversion resulting from a trauma in his youth. We also watch a play within a play put on by the residents; cutting between the community room and a dark, theatrical space lit by a sickly green light, we see our catatonics cast in a variety of awkward roles: a man in blackface, another in yellow face, a scarecrow, magicians. Sadly, their performances do not provide the expected healing, freeing effects expected; everyone seems to erode into further depths of despair and lifelessness. Having a last laugh, De Gruyter and Thys offer the characters the means to truly free themselves: not by making art, but by jumping out of a window.

Stills from »Der Schlamm von Branst«, 2008

Der Schlamm von Branst (The Clay from Branst) is a darkly humorous send-up of an art studio in which yet another cast of creeps appears, this time at work on a series of sad clay sculptures. One man gently works on a portrait bust that looks like an erect phallus, while another does the same to a horse’s head sculpted to look like a drooping one. A pair of men dressed in matching blue shirts and acrylic blond wigs drill holes into the various body parts of a prone human figure while a woman weeps over a raw block of clay, only later to pray to a sculpture of a human head. If here, art – or rather, bad art – is the product of the perverse and the pathetic, in The Frigate, art is what frees a pathetic perversity in its viewers. Commissioned for the 5th Berlin Biennial for Contemporary Art, the story follows the sexually charged antics of group of men, a single woman, and a lone cameraman, all propelled into deviance by a model of a frigate ship. One of the more disturbing sequences occurs as the men gather around the woman and hold poses to create compositions that echo a porn movie gangbang. One is left to wonder what is more perverse – pornography and violence, or the emulations thereof?

Untitled (No. 58), 2010

Perhaps the most menacing of De Gruyter and Thys’s videos is the recent Das Loch (The Hole, 2010), in which the artists have replaced their usual cast with sloppily constructed mannequins made of Styrofoam heads, thumbtacks and metal frames awkwardly costumed to stand as characters. »I make video films«, confesses a synthetic-voiced figure, who is little more than a hanging shirt beneath a foam head painted red, a mustache and goatee fringing a would-be mouth, and wrap-around sunglasses where eyes should be. The character’s voice continues on to tell stories about video projects, and to brag that he made a horror film with three girls, owns a Jaguar Mark 2, and how he once he killed a dog to win a race. His life, it seems, is full of self-serving pleasures.

His story is inter-cut with that of Johannes, a painter constructed from a neon yellow head and bad blonde beard whose sensitive, melancholy soul is crushed when his wife sees no potential in his work, and suggests he start making video films. Suicidal, he begs for death to relieve him of his body and return him to God. As he finishes his lament, we cut to close-ups on two Styrofoam heads painted black, one with green eyes, and one with blue. They speak: »We will break into all of your holes. We will do so until only one big hole remains. The black hole that smells of your death, we will break into that too. And when everything is broken into, we will start all over again. We are like that, we are like that.« But who are these destructive figures? Gods? Demons? Might they be stand-ins for De Gruyter and Thys, the video makers who certainly possess the power to end things as they see fit? Could we consider this a threat to artists both too sacred (the painter) and profane (the video maker) to be taken seriously? Of course, as befits De Gruyter and Thys’ dark humor, before these questions are answered, the image cuts out, leaving the audience – quite pointedly – in the dark.

JENNIFER KRASINSKI is a writer who lives in Los Angeles.

JOS DE GRUYTER, born in 1965 in Geel. HARALD THYS, born in 1966 in Wilrijk. Live in Brussels. Recent solo exhibitions include objekte als freunde, kestnergesellschaft, Hannover, Neuer Aachener Kunstverein (2011); Projekt 13, Kunsthalle Basel (2010); Culturgest, Lisbon; Kaleidoscope, Milan; Pro Choice, Vienna; Dependance, Brussels (2009); Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin (2008); Frac Le Plateau, Paris; Muhka, Antwerp; Carlier Gebauer, Berlin (2007). Recent exhibition participations include Yes, we don’t, Institut d’Art Contemporain, Villeurbanne; Parallel Worlds, Arsenal Berlin (2011); The State Of Things. Brussels/Beijing; Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels (2010); Come in, friends, the house is yours!, Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe (2009); Manifesta 7, Trentino; Berlin Biennale (2008).

His story is inter-cut with that of Johannes, a painter constructed from a neon yellow head and bad blonde beard whose sensitive, melancholy soul is crushed when his wife sees no potential in his work, and suggests he start making video films. Suicidal, he begs for death to relieve him of his body and return him to God. As he finishes his lament, we cut to close-ups on two Styrofoam heads painted black, one with green eyes, and one with blue. They speak: »We will break into all of your holes. We will do so until only one big hole remains. The black hole that smells of your death, we will break into that too. And when everything is broken into, we will start all over again. We are like that, we are like that.« But who are these destructive figures? Gods? Demons? Might they be stand-ins for De Gruyter and Thys, the video makers who certainly possess the power to end things as they see fit? Could we consider this a threat to artists both too sacred (the painter) and profane (the video maker) to be taken seriously? Of course, as befits De Gruyter and Thys’ dark humor, before these questions are answered, the image cuts out, leaving the audience – quite pointedly – in the dark.

JENNIFER KRASINSKI is a writer who lives in Los Angeles.

JOS DE GRUYTER, born in 1965 in Geel. HARALD THYS, born in 1966 in Wilrijk. Live in Brussels. Recent solo exhibitions include objekte als freunde, kestnergesellschaft, Hannover, Neuer Aachener Kunstverein (2011); Projekt 13, Kunsthalle Basel (2010); Culturgest, Lisbon; Kaleidoscope, Milan; Pro Choice, Vienna; Dependance, Brussels (2009); Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin (2008); Frac Le Plateau, Paris; Muhka, Antwerp; Carlier Gebauer, Berlin (2007). Recent exhibition participations include Yes, we don’t, Institut d’Art Contemporain, Villeurbanne; Parallel Worlds, Arsenal Berlin (2011); The State Of Things. Brussels/Beijing; Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels (2010); Come in, friends, the house is yours!, Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe (2009); Manifesta 7, Trentino; Berlin Biennale (2008).

Represented by Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin; Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp

Untitled (No. 142), 2010

Untitled (No. 155), 2010