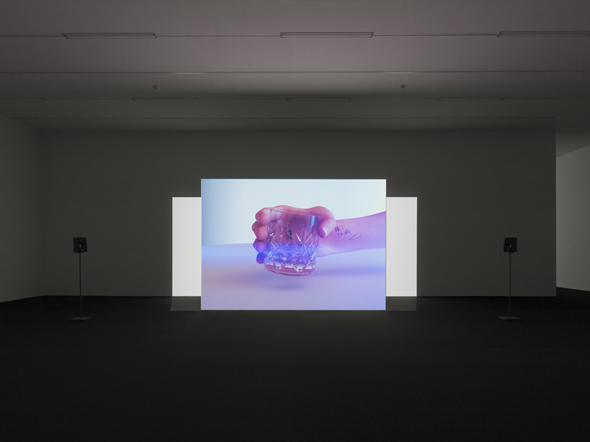

This is what an interesting exhibition looks like. It begins with large-format sheets of text loosely taped to the first wall in a contemporary, analogue, sloppy way. Rather than didactic introductions to the exhibition, they are abstruse hybrids, written in a style that implies we already know exactly what they’re talking about. There are torrents of words whose rhetoric and style immediately makes clear that the focus here is on text, and thus suggesting that the films in the following spaces should first be approached as texts, rather than as films. Then again these works aren’t actually films, but digital products posing as films. Take, for instance, the two-channel projection Us Dead Talk Love (2012), which features Atkins’s typical crude blend of kitsch, poetry, pomp, and seriousness along with an arsenal of so many digital special effects that it is almost funny. This highly artificial language is complemented by analogue content: »Sex, death. Intimacy and its melancholy impossibility«, as the bodiless head and avatar says in Us Dead Talk Love. The films are about the idea of distance, which is to say about the way digital media perform reality and are hence seen as reality or mistaken for it, just as in the 80s life was suddenly supposed to be simulation. This is a Western-centric view; in fact, however, the digital has infiltrated more corners of the world than anything that preceded it, generating unprecedented forms of proximity – or rather mere imitations of it. The ensuing sense of distance and alienation is the focus of Atkins’s films. They explore the essence of the digital and ask whether, as an entirely disembodied medium – as opposed to analogue film and photography, each with their specific physical materiality (celluloid, photographic paper, etc.) – it can even speak adequately about the body, about sex, death, intimacy, and love. It seems as if the more distant technology becomes from the body, the better it becomes at conjuring up an ersatz realistic physicality, as if a higher-quality prosthesis increased the pain in a phantom limb. This can be seen as technological progress but also as a mirror of life: the more experiences one hands off to the digital, the more powerful the longing for the body, even if only in the form of a tattoo. The artist puts it as follows in an interesting interview in the exhibition catalogue: »One of the fundamental gestures I want to make is one of rupturing this [mediation of experience by digital technologies].« He describes it as a gesture »of will, of an incoherent flailing if needs be – of desperation, love, violence; those things that speak rather clumsily and primally of human interaction«. There is plenty of Sturm und Drang in Atkins’s work, a virtuosic will to a reflective engagement of a kind – at once associative, narcissistic, and unabashed – that one rarely encounters in our post-disillusioned, post-ironic era. It is a kind of hypercoded expressionism that is aware of itself, its origins, and the accompanying problems, but which is nevertheless insistent – albeit in a way that is leavened by humor, which may well be what redeems it. Atkins’s works have something about them that is young and old at once. They are reminiscent of Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s famous Letter of Lord Chandos: if this fictionalized letter was emblematic of the crisis of language around 1900, the question is whether Atkins’s works are not emblematic of a similar crisis for a time in which the digital (which is nothing but pure language) is able to turn everything into infinitely variable codes and send it anywhere in disembodied form – as long as one has a smartphone and an Internet connection. This is clearly antagonistic to sex, death, intimacy, and love, which are bound up with the gravity of bodies: a resistance that cannot be overcome. And I wouldn’t have it any different.

DANIEL BAUMANN

Translated by James Gussen

© Stefan Altenburger Photography Zurich