Artists Space, New York 9.9.–16.12.2012

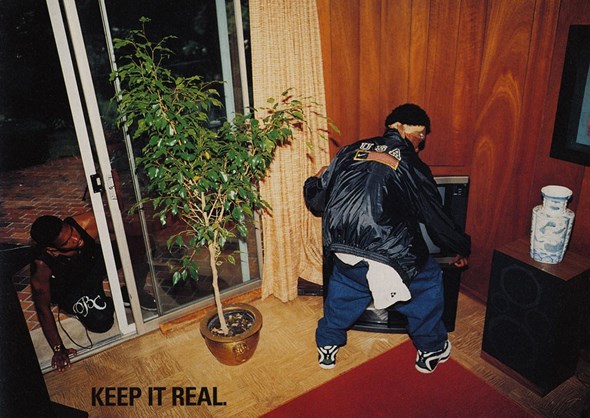

Photo: Daniel Pérez

A Story for Our Time

A sprawling, multi-panel chronology of Bernadette Corporation’s history included in their current retrospective at Artists Space pinpoints their formation in SoHo in 1993 as the initiative of one »Bernadette« and some others active in the neighborhood club culture. Across the many oversize panels, a story of the artist group’s activities unfolds in unnerving and hard-to-follow detail. Names, places, and various other points of reference – works produced by the collective, the context in which they were created – construct an oftentimes hermetic narrative; for all its breadth and depth, the chronology doesn’t offer the most user-friendly point of entry for the works on display, which are housed in a black, pseudo-minimal exhibition architecture.

But the objects present – clothing designs, which are much more street fashion than high fashion, branded »BC« (the logo form of the corporation’s identity); movie scripts; coffee mugs printed with poetry; high-gloss photos of a nubile model; and silk scarves; among other wares – are as curious as the architectonic display, and they benefit from the ether-thin frame of reference precipitated by BC’s co-option of conventionally institutional domains, such as historical contextualization and exhibition design. These works fare better, and can be best understood, in relation to rampant corporate opacity and mass markets of consumer goods. That’s the reality of today’s world, nowhere more present than in the neighborhood of New York that Artists Space inhabits and which Bernadette Corporation has scrutinized over the past twenty years – from the peddling of second-rate movie scripts on Canal Street to the high-end retail shops that now line the streets of SoHo. The group has done an unparalleled job of embodying (and simultaneously estranging, by satirizing) the place and the changes it has undergone.

Photo: John Minh Nguyen

One glaring absence in this exhibition, though, is a convincing treatment of Bernadette Corporation’s prolonged investment in the written word. Although one folding table is piled with copies of the screenplay »Eine Pinot Grigio, Bitte« and viewers can swipe through an ebook version of all three issues of »Made in USA« on iPads, these works’ reduction to an object or a screen is mistaken. One of the most remarkable aspects of Bernadette Corporation’s works – from the collectively authored novel Reena Spaulings to the handmade items of clothing displayed on mannequins – is that their substance is not merely located on the surface: time, effort, and intention (whether by an individual or a group) went into conceiving and generating the contents. Regardless of whether the novel is a good read, or a compelling life story, there’s plenty of life in it, and there’s something to that.

JOHN BEESON

Photo: Daniel Pérez

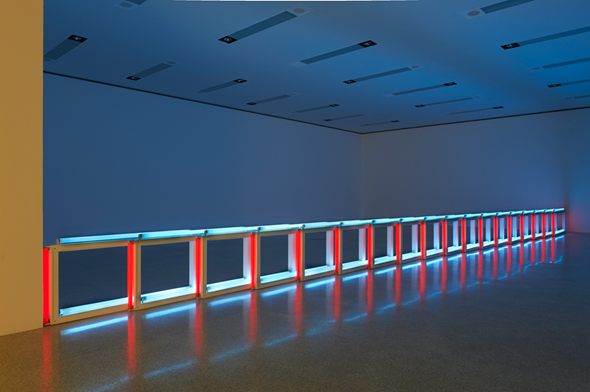

Dan Flavin »Lights«

Mumok, Vienna, 13.10.2012–3.2.2013

Illusion machine

Photos: mumok © Stephen Flavin/VBK Vienna

Michaela Eichwald »Der Meteorit soll kommen«

Mathew, Berlin, 1.11.–8.12.2012

Skein-deep

More than mere surface, Michaela Eichwald’s paintings have body, thin as it may be. Five of the six fleshy, chaotic, abstract paintings in her first solo show at Mathew in Berlin were made in the ten or so days before the exhibition – and with gallery dimensions in mind; the one which was not, Gerichtstraße (2011–2012), is hung, accordingly, at about a twenty-degree counterclockwise tilt. The visual effect of this is maddening in the best way possible, lending an unresolved concrete tension to an otherwise wholly abstract work.

As for that body, Nick Mauss and Ken Okiishi’s co-authored text for the exhibition designates a context for it that coincides cleanly with the discourse fostered both in the tradition of 80s and 90s Cologne – where and at which time Eichwald (*1967 in Cologne) was an active participant, collaborating with Jutta Koether and Kai Althoff, among others – and in the programmatic focus of Eichwald’s New York gallery, Reena Spaulings. Picking up on the second half of the title of one painting in this show, Memory-Klinik-Notluke-Persönlichkeitsschale (2012), translated as »escape-hatch personality shell«, these two young artists invoke the contemporary, neoliberal conditions of subject formation as it relates to the production and circulation of art works through social networks. Eichwald’s paintings, they suggest, refuse to locate their primary message within these networks, as indicated by the exchange between the artist’s body and her support surface during production and, after the fact, in the way that her rigorous abstractions resist tabulation into »readily exploitable data points to become »friends« with«.

This is one framework in which to locate the paintings, though perhaps not the single best one. For it proposes to calcify Eichwald’s intention into the creation of slippery impenetrability, whereas there are real points of reference in her work for viewers to relate to and find meaning in; this framework simultaneously reduces all approaches to the paintings – and paintings such as these – as a mirror of the process by which subjects are submitted to the structured social demands of selfidentifying, performing, and being creative.

Scrolling through recent posts on Eichwald’s assiduously updated blog uhutrust.com, one comes across a post (from October 21, 2012) with a reproduction of a page from a 19th-century book depicting a drawing of a meteorite’s fall to Earth; the lightning bolt-shaped trajectories drawn coming out of the atmosphere are apparently mimicked in Der Meteorit soll kommen (2012), one of the paintings on view and the namesake of the exhibition. That the access to these points of reference is mediated through Eichwald’s online presence is perhaps more indicative of today’s rampant access to self-publishing than it is of the work’s intention. Even before searching the Internet for more information about the artist and her work, in the gallery itself, in front of the paintings, sparks fly when connecting the exhibition title and the fabric serving as the support used in two of the works, which is patterned with stylized firework explosions. In fact, one need look no further than the skin of the paintings, where Eichwald has produced captivating, elaborate skeins of both gestures and washes in oil and acrylic paints, crayon and lacquer, prints from the bottom of her shoes and delicate folds in the substrate. These paintings are their own justification that viewers attend to them and not the heavy, if hollow, shell that may engulf both »friends« and »family« (Kippenberger’s word) in an exchange lacking substance.

JOHN BEESON

»Artist as Curator«

Symposium, Central Saint Martins, London, 10.11.2012

A short history of the curator

Three points of consensus emerged during Afterall Journal’s day-long symposium, an event which set out to explore the sometimes trickily-defined relationship between artists and curators: artists have historically been »allowed« greater liberties to experiment with exhibition-making than curators; there is a growing suspicion about the effect the globetrotting, »star« curator is having on exhibition making (notwithstanding the credentials of some of those speaking); and that it is hard to draw any firm conclusions differentiating the roles of artist and curator, due to the relative short history of the latter.

Elena Filipovic, curator at Wiels, Brussels, who co-curated the 5th Berlin Biennale with Adam Szymczyk in 2008, was the chief proponent of the first point. In a persuasively argued potted history, Filipovic compared historic landmark »curator-led« exhibitions – such as the 1913 Armory Show, Pictures at Artists Space, New York in 1977 and Magiciens de la Terre at the Pompidou in 1989 – to shows put together by artists. The comparison seemed to reveal the artist’s tendency to deconstruct and usurp the standard exhibition format: Duchamp’s 1917 alphabetically hung group exhibition, Yves Klein’s 1958 empty gallery, David Hammons’s 1995 unadvertised exhibition amongst the stock of a New York ethnographic antiques shop, and even the dematerialized display of post-Internet practice in recent years. It’s a seductive claim, and broadly speaking, given the social conditioning of the artist-as-genius cliché it probably holds water: to an artist, having another artist radically play with the presentation of their work is potentially more acceptable than letting someone from outside their discipline do so. Another speaker, Willem de Rooij, provided a case in point by having variously used works by Isa Genzken, Keren Cytter and Dutch designer Fong-Leng within his own installations. Yet Filipovic’s historical sketch is problematic: the early twentieth century exhibitions that weren’t organized by artists, weren’t in the hands of someone bearing the job title of »curator «, by our contemporary understanding of the term as a figure who provides theoretical or spatial contextualization to a set of art objects.

In their papers, Ekaterina Degot and David Teh similarly pointed out the historical non-existence of the »curator«, though specifically in relation to their respective geographic localities. Degot, a Moscow-based art historian, noted that in Soviet Russia, all art was presented through and by the artist unions. For his part, Teh expanded that exhibitions in southeast Asia have also always been staged by artists themselves. The nearest thing to what one might identify as non-artist curators operating in that area – historically at least – were either government bureaucrats, or alternatively, commercial gallerists. (Arguably, though, this remains broadly the status quo – Teh, an academic with a tendency for dense theoretical vocabulary, stated he could only maintain a career in Singapore by running a commercial gallery.) Answerable to either the state or the market, neither unproblematically fulfills the contemporary curatorial role.

De Rooij, the only artist to speak at the event, ran through some of the attributes one might ascribe to the curator title. »Choosing, displaying, contextualizing«, he began, before throwing a curveball by adding, »but these are really tasks I place within the job description of the artist. They are what I do when I make an object«. The contemporary curator must therefore stretch the topology they operate within far beyond these parameters. The pangeographical and durational nature of Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s documenta 13 – fluid and elastic in its endeavors, enveloping other disciplines, exercising itself beyond the exhibition spaces of Kassel into books and conferences and to farflung locations – is perhaps is a harbinger of this. The success of Christov-Bakargiev’s curation was not in creating just another show within a wider ecosystem, but in building her own ecosystem, spearheading a radical reconfiguring of the environment in which an art object operates.

OLIVER BASCIANO

Willem de Rooij spricht discussing his exhibition »Intolerance«, 2010

Photo: Line Ellegaard