House of Gaga, Mexico City, 30.3.–11.5.2012

Ephemera

Antek Walczak’s 2010 exhibition Empire State of Machine Mind at Real Fine Arts in New York featured four large paintings, or diagrams painted on canvas, depicting fragments of Jay-Z’s obnoxiously aspirational song broken down into Lempel-Ziv- Welch data compression code. Based upon pattern recognition, the Lempel-Ziv-Welch code speeds up the electronic transmission of language by parsing segments of text and then mapping these segments’ recurrence. A literal manifestation of the »machine mind«, Empire was an ingenious conceit. Composed of legible words like »New York« interspersed with circles and arrows, the four panels appeared as bitter one-liner jokes: the coded sentiment of the song reduced to its most elementally processed form.

Walczak’s recent exhibition at House of Gaga, The Lead Years, extends the artist’s fascination with the electro-mechanics of economic and libidinal control into something as mysterious as it is troubling. Realizing that emailed spam can be read as an anonymized mirror or a mechanical chorus of the culture’s concerns, Walczak went back to his junk mail archive from 2007, at the dawn of the economic collapse. He selected eight spams – market alerts, penny stock sales, currency future reports and loan solicitations – and had their texts screen-printed onto thin panels of lead.

The panels are heavy. They were purchased from a Mexico City metal supplier, who cut them to size. Though less than one millimeter thick, they require two people to lift them. Composed in international English for the purpose of phishing credit card information, the spammed texts themselves are non-sequiturs – strange combinations of exhortation, solicitation, stray reportage and alarm: »The system is also a good example of using busybox in an embedded system. To dissemble your feelings, to control your time, to do what everyone else was doing, was an instinctive reaction.« (Brotherhood, 2012); »Good credit or no, we are ready to give you a $ 378,000 loan.« (

As Walczak explained to me, »The purpose of spam is not to convey information … I don’t know how it is written. The literary idea of it is less interesting to me than how it circulates and mirrors the greater economy.« Installed in the gallery, the lead panels cast a dull, burnished glow; a toxic beauty. As Walczak writes in a preface to the exhibition, »The works draw on numerous associations with lead … chief among them being toxicity, in the scientific sense … and referring to certain financial assets, mortgage products, and even psychological-emotional moods. Coupled with spam, toxicity gains the capability of contagion, as thousands of emails flood peoples’ inboxes with simulated personal messages carrying payloads of scams, cons and viruses.« As toxic as lead itself, these messages circled the earth in the years leading up to the Global Financial Crisis, an era still referred to within certain markets as the Golden Years.

A member of the Bernadette Corporation since 1993, Walczak is a trenchant writer on aesthetics, economics and art. He is, in a sense, primarily a philosopher. Yet the eight Lead Years works enact a dazzling montage in which concept is, unexpectedly, perfectly joined to material and ephemera is memorialized. Lead, the »base metal« of alchemy, is transmuted here into something richer than gold.

CHRIS KRAUS

Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw, 18.5.–30.6.2012

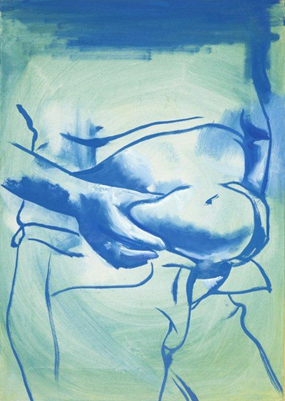

Oil on canvas

70 x 50 cm

Painter as Father

The small and intimate painting, hung separate from the others, marks the crux of the show. Two children are asleep on a bed – Kacper, around ten years old, lying on his stomach; and Rita, a toddler in a dark-blue playsuit, reclining on the pillow. The angular creases of the bed sheet resemble the expressive coats of medieval carved wooden figures of saints. There is an aura of the old masters discernible in this canvas, but the painting is nothing more than a scene of everyday family life – a cosy, informal moment frozen by a camera and then translated as a painting. It is mesmerizing.

The father of Kacper and Rita is Wilhelm Sasnal, the painter. The Father is also the title of his solo show in Foksal Gallery Foundation in Warsaw. Sasnal’s family has always been an inspiration for his work. The pregnancy of his wife Anka and the birth of Kacper constituted the plot of his early comic book The Everyday Life in Poland 1999–2001. It is the story of a recent alumnus of the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow – starting a family, struggling with his fledgling career, escaping reality in the seclusion of his studio and the music of his favourite bands. A decade later, he is on top, almost unanimously called »the best Polish painter«. Still, bearing the burden of this label, a recent Phaidon publication devoted to him, and undeniable success, Sasnal sustains a certain level of candidness and freshness, unashamed of the risk taking inscribed into his workaday style of painting. As painting for him is not a passing fad, he treats his turf seriously. Its sense of intimacy, however, does not result from any kind of exhibitionism. On the contrary, the process of painting, transforming the image onto canvas, conceals Sasnal’s privacy; it makes the photos on which his works are based blurry, irreversibly lost.

This exhibition, consisting of ten newly executed paintings, runs the whole gamut of genres: still life, large-scale landscapes, portraits and new pictorial allegories. There is something visceral in the whole selection. The scheme of a vestigial digestive system turns into abstract, baggy shapes, a formless thing. The flabby, porcine stomach, the souvenir of years of being a coach potato, is now grabbed and weighed in the character’s hands, his trousers unzipped. The moment the father figure spells »naff« – quite a dispiriting view, but not devoid of flippancy. The joy of parenthood melts with the fear of aging and deflating. What to do with that burden?

The uncanny leftover of watermelon is painted the way students used to paint at the academy – Sasnal stretched several layers of net curtain on the wooden frame; the surface is uneven, corrugated. Another canvas depicts a male figure sitting on a chair. A huge, beige-and-white blot replaced the child on his knee and covered his face. On the corresponding painting, the headless statue in the park had also lost its left calf, left arm, and right forearm – as if half-eaten, like the fruit on the opposite wall. The voids of a body are juxtaposed with its surpluses. The tension lies in disequilibrium.

Saying all that, slumbering children turn out to be as important in terms of subject matter as the sky, darkness, a chunk of watermelon or a pigsty. Sasnal paints shamelessly. A nocturnal view of a crossroad is poured by black paint, which left a net of narrow dribbles, like dark rain on a windowpane. When inspected closely, the rural landscape dissipates into abstract, colourful blots, dripped on the canvas in a way like Jackson Pollock.

Sasnal gets bogged down in a stalemate between what is revealed and what is hidden. His works exude confidence and the power of image-making. But, paradoxically, the steadfastness of his attitude makes him attractively vulnerable. Finally, one question poisoned my mind: What does it mean to have a painter as a father?

KAROL SIENKIEWICZ