All images: Courtesy Annet Gelink Gallery Amsterdam

With her work, the Israeli video artist YAEL BARTANA succeeds in breaking down the borders between documentation and myth, fact and fiction. Her most recent projects are charged with insightful provocations. By RAIMAR STANGE

Moving: cars travelling on a street in Tel Aviv at night are stoically filmed from above. Brilliant spotlights cast light on what his happening, cars rushing past are the only protagonists and continuous, electronically distorted traffic noise provides the sound –but suddenly sirens wail and the anonymous cars stop in the middle of the street. The car doors open and the previously unseen drivers and passengers get out. The people arrange themselves next to their vehicles, remain standing meaningfully and bow their heads devotedly. Shortly afterwards they get back in and drive on. Trembling Time (2001) by Yael Bartana focuses here on a moment that is repeated annually in Israel: the national minute of silence in memory of the fallen soldiers of Israel breaks into the daily routine of the country and enforces collective patterns of behaviour. Thanks to the use of filmic tricks, such as slow motion, crossfading and repetition, the Israeli artist is able to transform strangely the driving, stopping and standing into a smooth, artificially flowing trance.

As if in a microcosm, in Trembling Time four central aspects of the aesthetics of Bartana’s early work are condensed: material originally shot with documentary objectivity is worked up artistically through cutting and sound; seemingly unspectacular images, of a kind that do not flicker every day across the screens of the mainstream media but are definitely political in nature, are deconstructed to reveal their ideological character; everyday life and convention, politics and ritual confront each other so that individual and collective behaviour gather tension. The artist described this last aspect in thesewords: »I am interested in a state that prescribes a value system and the individual who is its recipient«. The way in which everyday courses of action are internalised in order to protect power from critical queries – that is not the least of what is being negotiated here. This is not just a theme for a state like Israel, which is under external pressure but is also potentially explosive in our own society. For example, the common act of crossing the road against the red light is no longer punished by the authorities, and not only in Germany, simply because the act of breaking the rules makes neoliberal ideology a matter of individual choice inthe truest sense: everyone decides for themselves what is right or wrong.

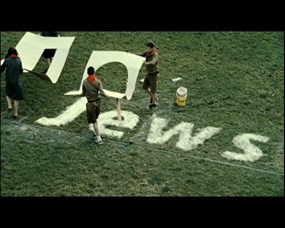

The two videos have in common not only that they take place in Israeli territory but also that the artist has staged none of the action. There is no script, just a composition in cutting and sound. Apart from that, Bartana builds on the semantic power – almost an »everyday myth« in the sense of Roland Barthes – of documentary film material. In later works this changes, for example in Wild Seeds (2005), a double projection with moving pictures and text inserts. The female voice of a reformed cantor sings off-stage about the love of God. The film shows young Israelis simulating a »violent evacuation of the Gilad settlement« in the West Bank itself. It is an almost theatrical re-enactment staged by Bartana and brought to life by young activists, imitating a real confrontation between the highly aggressive Israeli army and Jewish settlers.

This strategy is incidentally one used by recognised scholars, namely in the discipline of »historical econometrics«. In this form of historical research, the insight provoking power of scenarios is used to touch upon deliberately incorrect assumptions. The French cultural critic Michel de Certeau describes historical econometrics as a kind of research that »investigates the possible consequences of contra-factual hypotheses, such as: what would have become of slavery in the USA if the Civil War had never happened?«1 The third part of the Polish Trilogy is the performance We will be strong in our weakness (2010), where, particularly through textual presentations, Bartana’s artproject Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland is explained. We hear, for example, such programmatic sentences as: »You ask why we open up wounds and why we evoke old demons. We answer you thus: this is the only way for us to understand history,the only way for history to come to us.«

1 Michel de Certeau, Theoretische Fiktionen, Vienna 1997

Translated by Nelson Wattie

RAIMAR STANGE is a critic and curator. He lives in Berlin.

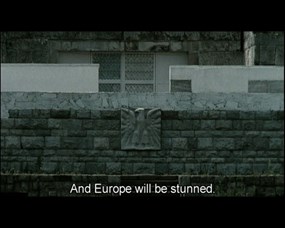

YAEL BARTANA, born in 1970 in Kfar Yehezkel, Israel. Lives in Amsterdam and Tel Aviv. Recent solo exhibitions include Yael Bartana … and Europe will be stunned, Moderna Museet Malmö; If you want, we’ll travel to the moon together!, Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam (2 010); Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw; Contemporary Jewish Museum of San Francisco; JewishMuseum, New York (2009); P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, New York; Center for Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv (2008); ThePower Plant, Toronto (2007). Group shows include Building Memory, Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art, Israel; LesPromesses du passé, Centre Pompidou, Paris; Morality ACT I I, Witte de With, Rotterdam; Early Years, KW Institute forContemporary Art, Berlin (2010); Earth: Art of a Changing World, Royal Academy of Arts, London; History of Violence, HaifaMuseum of Art, Israel (2009); She doesn’t think so but she’s dressed for the h-bomb, Tate Modern, London; Like an AttaliReport, but different, Kadist Art Foundation, Paris (2008); Documenta 12, Kassel (2007).

Represented by Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan; Kerstin Engholm Galerie, Vienna, Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam; Sommer Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv