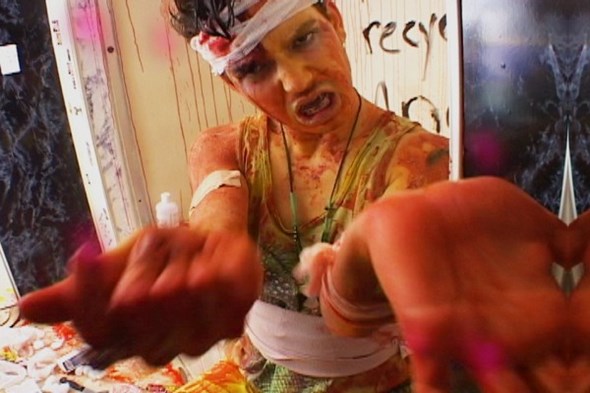

Still from »A Family Finds Entertainment«, 2004

The Now Voyager

Gender bending, skin paintings, wigs, bodies, souls, ids, and kids – welcome to the world of the young American video artist RYAN TRECARTIN. A portrait by JENNIFER KRASINSKI

Description may be an inescapable enterprise for a writer, but when the subject at hand has been made freely and pointedly available for all who are interested, any interpretation, or attempt at translation, enacts a very real betrayal. So before I begin, if you’ve not yet seen the video works of American artist Ryan Trecartin put down these pages and get to Googling. Although the artist publicly exhibits his work in galleries and museums, sometimes within installations made from pieces of his sets, other times alongside his sculptures and non-digital artwork, Trecartin has also uploaded nearly all of his videos online. No need to elbow the in-crowd for a seat, or wait years for a dusty but dutiful retrospective. A few clicks from now, you could be sitting face-to-interface with any one of his titles, from his earliest experiments to his most recent epics, and enjoying an unusually intimate and immediate access to a contemporary artist’s work, a rare pleasure that no ink, no matter how considerately spilled, could ever faithfully recreate or describe.

I absorb, and then I translate, and then I create. (Ryan Trecartin)

Ryan Trecartin is widely considered to be both the progeny and prodigy of »This Very Moment« in the unrelenting Digital Age. In fact, when he first appeared on the scene in 2005, some talked about his presence as though he had materialized from the ether, crawled through networks of high-speed cables and hyperlinks to blow up all over our home computer screens with his spellbindingly anarchic videos. People commiserated about the close encounters they’d had with Trecartin’s hardwired, hyper-color characters, exotic creatures who yammer in nu-slang and quick-pose through genre mash-ups with eye-blistering velocity. Although his world appeared alien, his predilections for suburban »objets«, thrift store wardrobes, craft store materials, and pre-packaged special effects were the proof that he was indeed of this planet. Striking too was the unabashed queerness of Trecartin’s citizens – Boys? Girls? Whatevs. – inspiring others to pronounce him the test tube child of experimental ferocities like Jack Smith, John Waters, and Leigh Bowery, though his face, when cleaned of paint and smiling for a press picture, bears a closer resemblance to a young Jeff Koons.

I absorb, and then I translate, and then I create. (Ryan Trecartin)

Ryan Trecartin is widely considered to be both the progeny and prodigy of »This Very Moment« in the unrelenting Digital Age. In fact, when he first appeared on the scene in 2005, some talked about his presence as though he had materialized from the ether, crawled through networks of high-speed cables and hyperlinks to blow up all over our home computer screens with his spellbindingly anarchic videos. People commiserated about the close encounters they’d had with Trecartin’s hardwired, hyper-color characters, exotic creatures who yammer in nu-slang and quick-pose through genre mash-ups with eye-blistering velocity. Although his world appeared alien, his predilections for suburban »objets«, thrift store wardrobes, craft store materials, and pre-packaged special effects were the proof that he was indeed of this planet. Striking too was the unabashed queerness of Trecartin’s citizens – Boys? Girls? Whatevs. – inspiring others to pronounce him the test tube child of experimental ferocities like Jack Smith, John Waters, and Leigh Bowery, though his face, when cleaned of paint and smiling for a press picture, bears a closer resemblance to a young Jeff Koons.

But in truth, Ryan Trecartin was born in 1981 of actual parents, and grew up in both Texas and rural Ohio (alien nations of a kind, I suppose), and when telling his own story, he professes that his earliest obsessions were music and dance. (He also claims the film Dirty Dancing as a strong influence). He, like others of his generation, has had a brimming bank of media memories burned into his brain by first the cathode ray, then the computer screen. He remembers watching his babysitters watch MTV, its deep hold on them made obvious by the way they dressed and talked and aspired. In his last year of high school, he got his first video camera. The following fall, he enrolled at the Rhode Island School of Design where he made his initial forays into video art with shorts like Kitchen Girl (2001) and Valentine’s Day Girl (2001), both quick and freaky takes on frustrated femininities (The Mother, The Single Girl), and both starring fellow student (and one of Trecartin’s closest collaborators), Lizzie Fitch.

Thereafter came Yo A Romantic Comedy (2002) which featured a twisted pair of wannabes arguing in a mutant strain of tabloid talk about whether or not to have a baby (»I am a maternity bitch.«); Wayne’s World (2003), a sweet send-up of music videos starring both Lizzie and Ryan; and What’s The Love Making Babies For (2003) a comedic meditation on the nature (and questionable naturalness) of gender, sexuality, and reproduction. In one sequence, Trecartin looks into the camera as he tucks himself, stuffs himself, suits up and mustachios to become Father God – a man in male drag – as the word »Comercial« [sic] written in hot pink cursive appears over his image. »No one’s perfect,« he tells his target audience, »I enjoy an entertaining lifestyle. So entertain me.« Here, God – though a smarmy huckster – may be all loving and all-forgiving, but still needs something interesting to watch once in awhile.

Thereafter came Yo A Romantic Comedy (2002) which featured a twisted pair of wannabes arguing in a mutant strain of tabloid talk about whether or not to have a baby (»I am a maternity bitch.«); Wayne’s World (2003), a sweet send-up of music videos starring both Lizzie and Ryan; and What’s The Love Making Babies For (2003) a comedic meditation on the nature (and questionable naturalness) of gender, sexuality, and reproduction. In one sequence, Trecartin looks into the camera as he tucks himself, stuffs himself, suits up and mustachios to become Father God – a man in male drag – as the word »Comercial« [sic] written in hot pink cursive appears over his image. »No one’s perfect,« he tells his target audience, »I enjoy an entertaining lifestyle. So entertain me.« Here, God – though a smarmy huckster – may be all loving and all-forgiving, but still needs something interesting to watch once in awhile.

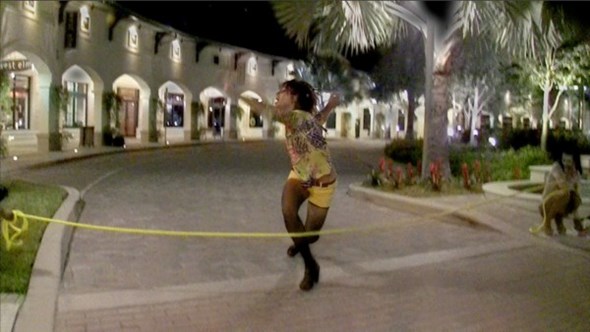

Stills from »A Family Finds Entertainment«, 2004

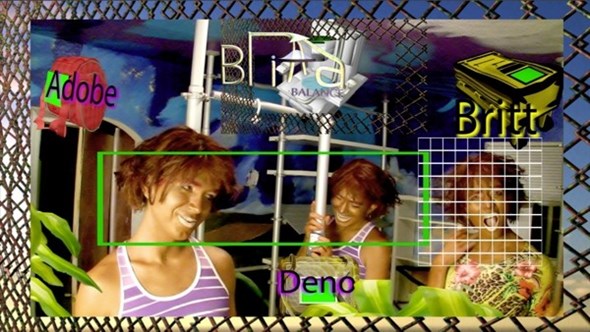

I-Be Area (Installation views Elizabeth Dee Gallery, New York), 2007

It was his senior BFA project, A Family Finds Entertainment (2004), which not only commanded the attention of the art world, it was included in the 2006 Whitney Biennial, but also crystallized the coordinates on which »Trecartinesia« (to borrow from writer Wayne Koestenbaum) would map itself: gender bending, camera addressing, grammar humping, skin painting, seam ripping, wigs, bodies, souls, ids, and kids are the strategies and subjects that continue to appear and reappear throughout his work. A too-brief synopsis (for his narratives are dense, feral): A Family Finds Entertainment self-stars Trecartin as Skippy, a maniacal young man who skips his own party to writhe and blurt and cut himself in the bathroom mirror before running outside to be killed by a passing car. Elsewhere (though where exactly is a always question), other delinquents clown for the camera, and await a documentary filmmaker who may (or may not) be shooting them today. Shattered by his masterful use of home-spun digital effects – superimposed images, kaleidoscopic frames within frames, all edited with a rhythm, precision and attention to gesture that would even impress Bob Fosse – the effect is disorienting, disillusioning. Adding torque to the vortex in which the viewer finds him or herself, Trecartin’s characters address the camera directly (most of the time), whether having a conversation with another character, or just talking to themselves. It doesn’t seem to be the usual desperation for attention that marks Population T’s relationship with the camera – it’s far too comfortable, too business-as-usual (though as a viewer, one certainly feels stared at, challenged and invaded).One might say that Trecartin’s people are just barely able to contain themselves – literally. But is this simply the Narcissism of the young-and-online? And is Narcissism the fair and accurate description? Doesn’t pathology unleashed as common practice relegate this kind of damning diagnosis to a pastime for the old-and-out-of-it?

Trecartin’s next major work, I-Be Area (2007), was also his first feature-length movie. This time, identity and its many mutations seem to be Trecartin’s subjects. Originals argue with avatars and other alt-versions of themselves; lives are available for sale or trade and can be passed around all neat and complete in convenient carrying cases; online adoptions are prompted by the need for new talent in the family; and names sound like multi-culti branding attempts: Progressica, Amerisha, Ramada Omar. What sifts upward from the chaos is that these characters have no need for history; it just clutters your hard drive. Empty the trashcan, man. Lineage is a thing of the past. »Why do I have a belly button?« drawls I-Be (played by Trecartin) as he shows his friends the homemade putty patch on his navel. »It don’t relate to my life. So I filled it in.«

One of the many delights of I-Be Area is watching Trecartin’s growing gaggle of friends and collaborators appear and reappear both on and off screen (in addition to Fitch, watch for Rhett LaRue, Veronica Gelbaum, Allison Powell, Raul DeNieves, and assorted other dazzlers). Unlike other contemporary artists who invest in celebrity cameos, Trecartin rounds up his troupe from assorted college friends, colleagues and other freaky people he finds. Like Warhol before him, he seems to use his stable as muse and medium; unlike Warhol, the artist and his performers are often painted and costumed to the point of being almost unrecognizable, his close-ups having little to no reverence for the supremacy of the face. But isn’t anonymity where it’s at? And – isn’t celebrity so 20th century anyhow?

I don’t want a body anymore. Fuck the body. I want a soul. And I’m gonna make my own soul. ‘Cause I’m not gonna wait and find out if I have one or not. (from Sibling Topics)

Last year, Trecartin premiered three new videos under the title Trill-ogy Comp, which belong to the eight-part epic Any Ever: K-Corea INC. K (Section A), Sibling Topics (Section A) and P.opular S.ky (section ish), all 2009. Consumerism and the failing economy are two of his targets this time, his guiding principle, the trill (in music, the quick alternation between two notes). His homophonies vibrate at an incredible rate, creating one of his densest and most challenging videos yet. Talking about these pieces in an address to the students at The Tyler School of Art on the occasion of his being the winner of the first annual Jack Wolgin International Competition in the Fine Arts, Trecartin described a software he would like to design that would allow his audiences to type in character names or other words of interest in order to follow certain narrative threads, creating what he called »sequential events of your choice«. The proposition of this kind of open source art isn’t new, but in a market founded on originals and editions, Trecartin would be offering an army of avatars for a single work of art, one that could have as many versions as there are viewers. And there we would sit – artist as content provider, audience members as editors, each of us creating our own desktop version of a Ryan Trecartin – all of us now artists at work.

Trecartin’s next major work, I-Be Area (2007), was also his first feature-length movie. This time, identity and its many mutations seem to be Trecartin’s subjects. Originals argue with avatars and other alt-versions of themselves; lives are available for sale or trade and can be passed around all neat and complete in convenient carrying cases; online adoptions are prompted by the need for new talent in the family; and names sound like multi-culti branding attempts: Progressica, Amerisha, Ramada Omar. What sifts upward from the chaos is that these characters have no need for history; it just clutters your hard drive. Empty the trashcan, man. Lineage is a thing of the past. »Why do I have a belly button?« drawls I-Be (played by Trecartin) as he shows his friends the homemade putty patch on his navel. »It don’t relate to my life. So I filled it in.«

One of the many delights of I-Be Area is watching Trecartin’s growing gaggle of friends and collaborators appear and reappear both on and off screen (in addition to Fitch, watch for Rhett LaRue, Veronica Gelbaum, Allison Powell, Raul DeNieves, and assorted other dazzlers). Unlike other contemporary artists who invest in celebrity cameos, Trecartin rounds up his troupe from assorted college friends, colleagues and other freaky people he finds. Like Warhol before him, he seems to use his stable as muse and medium; unlike Warhol, the artist and his performers are often painted and costumed to the point of being almost unrecognizable, his close-ups having little to no reverence for the supremacy of the face. But isn’t anonymity where it’s at? And – isn’t celebrity so 20th century anyhow?

I don’t want a body anymore. Fuck the body. I want a soul. And I’m gonna make my own soul. ‘Cause I’m not gonna wait and find out if I have one or not. (from Sibling Topics)

Last year, Trecartin premiered three new videos under the title Trill-ogy Comp, which belong to the eight-part epic Any Ever: K-Corea INC. K (Section A), Sibling Topics (Section A) and P.opular S.ky (section ish), all 2009. Consumerism and the failing economy are two of his targets this time, his guiding principle, the trill (in music, the quick alternation between two notes). His homophonies vibrate at an incredible rate, creating one of his densest and most challenging videos yet. Talking about these pieces in an address to the students at The Tyler School of Art on the occasion of his being the winner of the first annual Jack Wolgin International Competition in the Fine Arts, Trecartin described a software he would like to design that would allow his audiences to type in character names or other words of interest in order to follow certain narrative threads, creating what he called »sequential events of your choice«. The proposition of this kind of open source art isn’t new, but in a market founded on originals and editions, Trecartin would be offering an army of avatars for a single work of art, one that could have as many versions as there are viewers. And there we would sit – artist as content provider, audience members as editors, each of us creating our own desktop version of a Ryan Trecartin – all of us now artists at work.

Stills from »Siblings Topic (Section A)«, 2009

JENNIFER KRASINSKI is a writer who lives in Los Angeles.

RYAN TRECARTIN, born in 1981 in Webster, Texas. Lives in Philadelphia. Recent solo exhibitions include a. o. The Power Plant, Toronto (2010); Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2008); I-BeArea, Elizabeth Dee Gallery, NewYork (2007); I Smell Pregnant, QED, Los Angeles (2006). Exhibition participations include Virtuoso Illusion: Cross Dressing and the New Media Avant-Garde, MIT/List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge (2010); 100 Years (version #1), Number Three: Here and Now, Julia Stoschek Foundation, Dusseldorf; 100Years (version #2), P.S.1,NewYork; The Generational: Younger than Jesus, The New Museum, New York; Installations II: Video from the Guggenheim Collections, Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao (2009); Busan Biennale, South Korea; (2008); Between Two Deaths, ZKM Karlsruhe (2007);Whitney Biennial, Day for Night, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2006).

Represented by ELIZABETH DEE, New York; ANGSTROM GALLERY, Los Angeles /Dallas

RYAN TRECARTIN, born in 1981 in Webster, Texas. Lives in Philadelphia. Recent solo exhibitions include a. o. The Power Plant, Toronto (2010); Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2008); I-BeArea, Elizabeth Dee Gallery, NewYork (2007); I Smell Pregnant, QED, Los Angeles (2006). Exhibition participations include Virtuoso Illusion: Cross Dressing and the New Media Avant-Garde, MIT/List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge (2010); 100 Years (version #1), Number Three: Here and Now, Julia Stoschek Foundation, Dusseldorf; 100Years (version #2), P.S.1,NewYork; The Generational: Younger than Jesus, The New Museum, New York; Installations II: Video from the Guggenheim Collections, Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao (2009); Busan Biennale, South Korea; (2008); Between Two Deaths, ZKM Karlsruhe (2007);Whitney Biennial, Day for Night, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2006).

Represented by ELIZABETH DEE, New York; ANGSTROM GALLERY, Los Angeles /Dallas