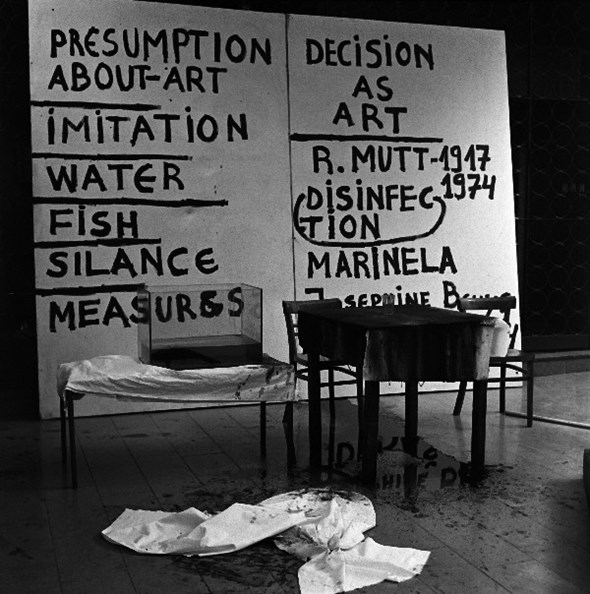

Performance at Students Cultural Centre, Belgrade, 1975

Photo: Marinela Koželj

The Belgrade art scene of the seventies, early performances and short stories on art. HANS ULRICH OBRIST interviews RAŠA TODOSIJEVIĆ

HANS ULRICH OBRIST: Let’s start at the beginning.

OBRIST: Fiction?

TODOSIJEVIĆ: Most of them are fictional because I don’t like the truth. Art is fiction, art is not real stuff.

OBRIST: You have been writing quite regularly, first as a critic and then this fiction. Is it a daily or a sporadic practice?

TODOSIJEVIĆ: Unfortunately it’s a daily practice. Unfortunately. I don’t like to write! (Laughs) I say to myself, »I am a very busy lazy man«. It’s a contradiction! I am a busy, busy, lazy, lazy man. (Laughs) So I spend a lot of time writing short stories. I don’t like to put myself in competition with writers and art critics and curators. I am writing my small stories and I don’t bother anybody.

OBRIST: In the sixties you were part of the group New Art Practice, a group of six artists including Zoran Popovic, Nesa Paripovic, Urkom Gergely, Marina Abramovic and Era Milivojevic. It didn’t last very long and yet it was a very important moment in the Belgrade art scene.

TODOSIJEVIĆ: The group was together about three or four years. We were together in the academy, spitting at our professors; we were so dissatisfied with the situation as young, but bloody smart, artists. Really! Our professors were lazy, fat and stupid people so when we came back after the summer holidays we turned around and said, »All this stuff you are talking about is not true; we saw the actual pictures and you are wrong«. But in relation to authority we were forced to be silent and not openly spit at the professors. Our only strategy was not to work; in our last year in the academy we gave up going to the school every day. Soon after the academy we started going into the Students’ Cultural Centre and we said we were coming to bring new things, we were going to make new art in Belgrade. Really believe me, we wanted to change things – killing the father, which I enjoy. But Freud was not quite correct about that killing. This killing lasted a long time; it didn’t take just a moment. (Laughs) Secondly, we gave up on the regular galleries. The Students’ Cultural Centre gave us a chance to make art as we wished and to make exhibitions as we wished. We thought, next Saturday we want to make a show. OK. No waiting for the show or applying for a time slot. And thirdly we said we have to use our friendships from abroad and bring foreign artists to Belgrade to show that we were not something strange, that we were actually following a regular practice, because when we started people said, »Those kids are idiots, they make such stupid things, such things don’t exist anywhere«. We started to invite foreign artists, who were not well-known at the time; now most of them are mega super stars like Francesco Clemente for example, Jannis Kounellis or Chiari or Gina Pane, Daniel Buren, Joseph Beuys …

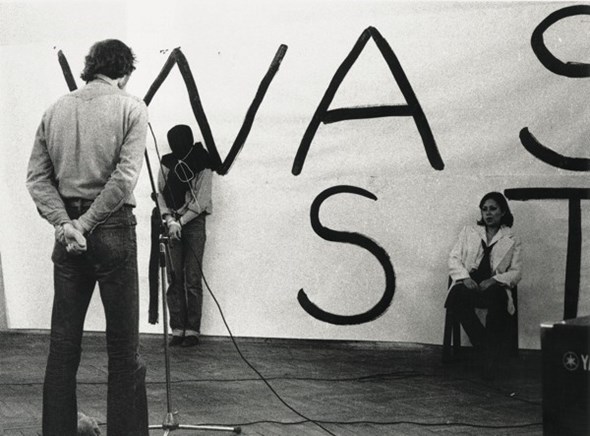

Performance, Students Cultural Centre Belgrad, 1960s

Foto: Marinela Koželj

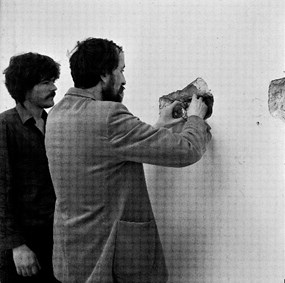

International Performance Festival, Vienna

Photo: Tom Marioni

Performance, SKC Gallery, Belgrade

Photo: Miša Savić

OBRIST: What linked you to Marina Abramovic and her first husband, Nesa Paropovic?

TODOSIJEVIĆ: Friendship.

OBRIST: Not the work?

TODOSIJEVIĆ: No. Generally we shared the intention of bringing something new; the new at the time was a nebulous idea. It was a very productive time; we started to make manifestos, posters, movies, performances, texts, photos, actions, so-called »aleatoric« works, body works and so on.

OBRIST: What is your take on revolution? In the early nineties, the Cuban- American artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres told me, »Revolution is a waste of energy«. Would you agree with that?

TODOSIJEVIĆ: Yes and no. Sometimes artists have to deal with utopia. Sometimes, not every day. The artist’s role is not to anesthetize politics but to politicize aesthetic politics.

OBRIST: Did you publish your manifestos in magazines?

TODOSIJEVIĆ: At that time there were only one or two art magazines in Yugoslavia. So I usually published my stuff in some sort of literary magazine which didn’t care much about art. (Laughs) It was much easier. »Who makes profit on art?«, »Who is for art and why?«, »Who is against art and why?« These were long articles, twenty pages.

OBRIST: It also had a lot to do with the economy.

TODOSIJEVIĆ: Yes, yes. Even though we lived in the West, during the 60s and 70s there was the idea here that there was the basis, the infrastructure and metaphysics. Work is the basis, money the superstructure and art is somewhere higher. I said no, art is the basis, beer is the basis, beans are the basis. Yes, sort of dealing with the economy. Who makes profit on art? I said that all of society is involved in art. That’s the point.

OBRIST: When did you do your first body performance?

TODOSIJEVIĆ: The first real performance was in 1970. We did it together in Edinburgh, there was me, Marina, Zoran Popovic, Urkom Gergel, and Jasmina Kalic.

OBRIST: It was called The Citizen as Art at Melville College. Can you tell me what happened there?

TODOSIJEVIĆ: It was a bloody long time ago … I had a goldfish; I threw the goldfish on the floor and started to paint my body with mud and ran through Melville College waiting for the fish to die. People said, »God, please bring the goldfish back to the aquarium« and they started crying about fish. They eat so many chickens every day, why are they crying about fish? My wife was sitting very, very still in contrast to me.

OBRIST: You’ve worked with memory since the 70s and you did this famous Memoria piece in 1975.

TODOSIJEVIĆ: I said to myself, come and recite all the names of all the artists from the entire history of art you can remember. It was pretty long. But I didn’t make any system. I started to say all the names. It was a long, long and heavy performance of all the names. The name of that performance was Art and Memory. I did this performance without rehearsals. I sat by the table with a microphone and started recalling the names of all the artists I knew. Symbolically I started with Altamira. I instinctively helped myself by following some historical chronology: Sumerians, Assyria, Babylon, Egypt, Crete, Greeks and so on until the Modern age, the 20th century. My art history is only that which I can hold in my mind. My memory is the boundary of my art history.

Pencil on paper, each 100 x 30 cm

Photo: Reljić

Installation view at SKC Gallery, Belgrade

Photo: Marinela Koželj

TODOSIJEVIĆ: Yes. I am now preparing an opera.

OBRIST: Can you tell me more about it?

TODOSIJEVIĆ: I like being in an end of the nineteenth century mood. (Sings). Another sound piece is one with a transistor radio. I turned the radios on to different radio stations, plastered them in paint and they were completely unidentifiable. I called it Invisible Sculpture - Endless Music. I dug three holes in the gallery wall and placed three transistor radios into them. Then I plastered the holes and finished the wall with sandpaper and painted it in regular white paint. The sculpture was invisible and from that time on the music was endless. The radios are still in the wall of the gallery of the Student’s Cultural Center, more than 20 years later. There is another point of this work, one traditional point, which was the idea of sacrificing somebody for the success of the buildings.

OBRIST: Invisibility also plays a role with your works in the white cube, doesn’t it? You did this marvellous one line in a deserted house; one line in a certain house, then ten thousand lines in the gallery.

TODOSIJEVIĆ: I started discussing work and practice and first I jumped at the idea of no day without lines, meaning that progress comes when you work every day. So I said, »OK. I will follow the instruction literally. No days without lines«. It’s also ironic. (Laughs) So I made One line in a deserted house and 200,000 Lines for the Paris Biennale. I was making a joke, analyzing, and I was doing one line over there – you cannot tell how many lines are there. I said 150,000 lines. But then I stopped working with this idea because people instantly connected those activities with the ideology of Minimal art.

OBRIST: Your practice has been considered to be very conceptual and there has been a lot of discussion ever since the 60s about the notion of the nomadic artist, and there has also been a lot written about you being a nomadic artist. Does the nomadic artist create wherever he or she is?

TODOSIJEVIĆ: Nomadism is a metaphor. It’s not really a cowboy who is going from one place to another. It’s a metaphor for the artist’s ability to jump from one topic to another. It’s not really nomadic to go from Belgrade to Kansas City. It’s an idea; it’s the ability to change topic. This is what is nomadic because in previous times they said an artist finds his time; when he finds and catches his style, all his life he produces the same stuff. So the idea of nomadic art is the idea of being free to change topics, to jump from performance to sculpture, from sculpture to painting. I was doing this in the 60s and the beginning of the 70s …

OBRIST: Was IRWIN influenced by you?

TODOSIJEVIĆ: Yes, particularily by the performance Was ist Kunst. The first version of the band Laibach was also influenced. They started using the German language, violence and most of all the retro-principle. The problem was that people were fascinated by the idea of my performance Was ist Kunst? I repeat it in German. Everybody was surprised: »Why are you using German? Everybody uses English?« I said you cannot say Was ist Kunst? so brutally in English. You cannot say it in French.

OBRIST: That was 1976-81, so it was a five year performance cycle. Can you tell me about Was ist Kunst?

TODOSIJEVIC: Yes. Very simple. I started beating my wife. (Laughs) It’s simple. All the people came out dreaming [of beating their wives]. (Laughs) I said it is hard work and then started beating her and asking her »Was ist kunst?«. Then galleries invited me, some in the East, in Slovenia, in a deserted area, an island. It was deserted because the Italians had left the countryside and the area was empty, only old women and young mentally handicapped people lived there. So I said, »What to do? My God it is such a zero culture zone!« There was one Austrian girl, Patricia Hennings, she had an oriental face, she was South American. So I put her face in front of the camera and began shouting, »Was ist kunst? Was ist kunst?« And people said, »Such a simple thing to do. It sounds very good. Why didn’t we think of that?« So later on I started my performance beating my wife, putting a collar on and hitting like someone doing a police interrogation. Was ist Kunst? was a good chance to make an ironic comment on that mentality.

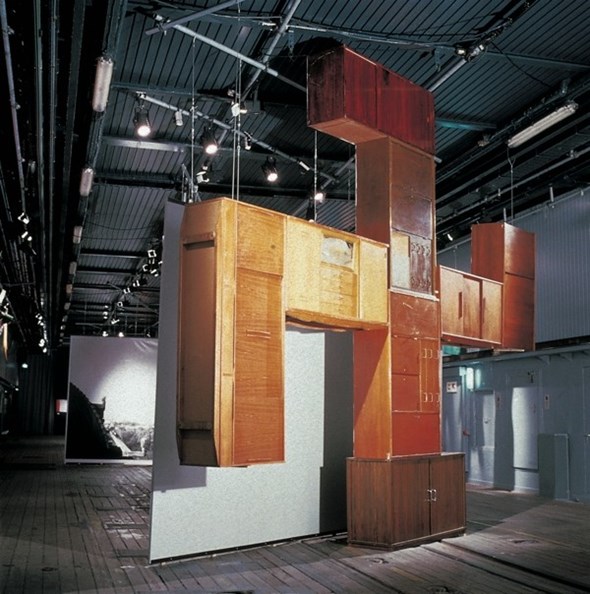

Installation view, Museum of Contemporary Art Belgrade

Photo: Marinela Koželj

OBRIST: I was wondering how you think about the political dimension of your work. Laibach considered themselves to be political so I wondered if they were influenced by you, in the political aspects of your work.

TODOSIJEVIĆ: They always criticized me and said that I was a liar when I said my swastikas were not political. It’s dealing with meaning. The swastika can be found in Indian, Chinese and Japanese traditions, in almost all tribes in pre-Columbian America, in ancient Greece, in Celtic tradition and Eskimo tradition, in Ancient Rome, etc. … After the Second World War and the experience of National Socialism, the swastika has become to be perceived as a symbol of evil. There are no symbols, per se – we give them a meaning. Gustav Courbet painted »The Painter’s Studio« – one of the first pictures that didn’t carry an explicit message with it, but rather let its meaning be formed in the eye of the beholder. Which is only a step away from Duchamp's readymades. Courbet, like Duchamp, belonged to different and not particularly serious, esoteric circles and it is certain that the readymades did not originate from a discourse on art.

OBRIST: Can you tell me about your Condolence Book?

TODOSIJEVIĆ: Many times in history people have proclaimed that art is dead. Every day »art is dying«; morning, noon and night. At the time it was the fashion to talk about the death of art because art is always dead and living art is deception. So I said, »OK if you believe that art is dead I will make a Condolence Book so people can come and express sympathy for the death of art«. It was an ordinary book which people could come write in. I remember the first person who signed it was Achile Bonito Oliva.

OBRIST: Thank you so much for this interview.

RAŠA TODOSIJEVIĆ, born 1945 in Belgrade. Lives in Belgrade. Selected Exhibitions (since 2004). 1st floor gallery, Antwerpen (2006), Centre for graphics and visual research, Belgrad (2006), National Museum of Montenegro (2005). Selected group shows since 2004: »Private space – Public space«, Culture Centre Magazine Nolit, Belgrad (2007), »Conceptual Art 1968 – 2007«, Museum of Contemporary Art, Novi Sad (2007), »Kontakt … aus der Sammlung Erste Bank«, MUMOK Wien, Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrad (2006), »Tranzit«, Frankfurter Kunstverein, Frankfurt (2006), »Reading«, The Society of Independent Artists, San Francisco (2006), Istanbul Biennale (2005), »Parallel Actions«, Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst, Leipzig (2004), »BELGRADE ART INC«, Secession, Wien (2004), »Parallel Action«, Austrian Cultural Forum, New York (2004)

HANS ULRICH OBRIST is Co-director of Exhibitions and Programmes and Director of International Projects at the Serpentine Gallery, London.

Installation view of »Europe Discovered«, Kulturbot, Copenhagen

Photo: Mrdjan Bajić