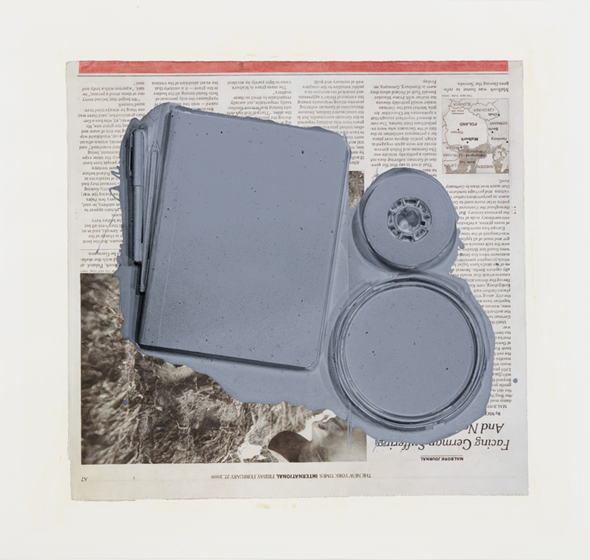

Ink and enamel on paper

A Certain Kind of Realism

PAUL SIETSEMA, an artist whom at least two upcoming generations will title as »the artist of the generation«, we heard someone say. »Sietsema – the best-kept secret of the last decade«, was another remark. It remains to be seen if any of this is true, but for the time being we have a piece by Jonas Žakaitis trying to look at the works and into the mind’s inner workings of this enigmatic American artist.

I

The only time I met him was maybe 30 years ago. It was summer in Lithuania, and we had all gathered in a small resort by the lake for this big national humanities conference. We: young graduates in our midtwenties. Philosophy students, art critics, anthropologists, promising theatre directors yet to stage their first plays; a group of rebellious poets – in general, an inedible broth of sarcasm, postcolonial theory, hope, egomania and uncontrolled erections manifesting itself through long quotes from Heidegger’s Being and Time. We were all drinking heavily, cheapest wine and beer, eating greasy potato pancakes, barely sleeping at all; each emitting at least five words per second on any given subject, William Carlos Williams vs. Ezra Pound, Heidegger and the beginnings of philosophy, the semiotic square, Carl Schmitt, Le Vide. A pulsating wall of sound, pure potential energy.

We had all heard some biographical facts about him, but nothing for sure. Apparently, he was an old Lithuanian émigré who left for the US before the war while still in his teens. Ended up fighting in Japan, getting an American passport, studying philosophy in Chicago and then Freiburg, within two years published a series of articles on phenomenology that made even German academia believe in Husserl’s reincarnation, and then suddenly dropped everything. Went back to the States and spent 40 years teaching in the smallest provincial university nobody had heard about without publishing a single word ever since. When he showed up at that conference for some reason or another, a very old man barely remembering a word in Lithuanian, all of us distinctly saw a blue halo of mysterious genius around his bald head. He looked like Nabokov’s wax sculpture with a permanent half-smile, eyes blurred out under thick rimmed glasses, legs and arms moving in senile staccato but somehow also very lightly.

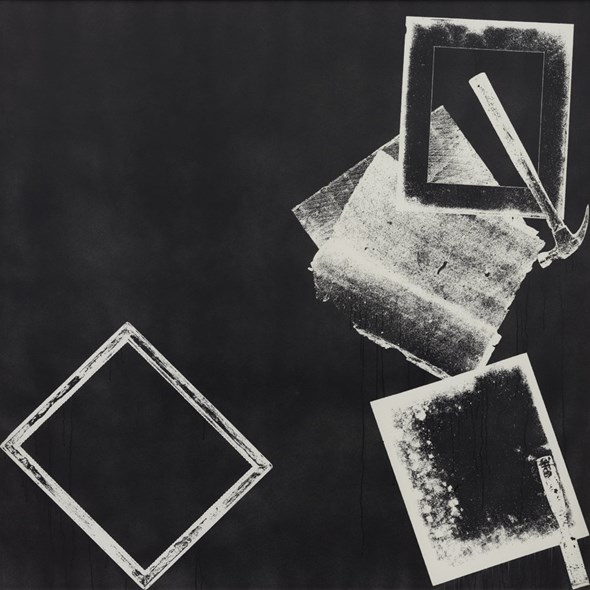

Ink on paper

I remember one night we were all drinking in a narrow corridor of a hotel, squatting on the floor in an orchard of bottles and cigarette butts, and at some point he silently joined us. It was really late, but the old man seemed to be enjoying himself, drinking the cheap wine with us and listening to the endless overlapping monologues. No one dared address him directly, but everyone fought for his attention as if expecting some kind of a verdict. In the end nothing happened. Whenever you think about something he said, whenever you think about something – this is the only thing that he said that night – you are already outside of that thing. And if you think about a thought, you are already outside of that thought.

Some twenty years later I visited his widow in Southern Ohio. I was on my way to another conference, a bigger one this time, more mature and sober, but also hopeless and boring (the conference). The old lady was still living alone in their house. A red brick building wearing three white isosceles triangles as rooftops – one on the garage, one above the entrance door and one on the main house. How do you look after all this space, I asked her. I don’t, she said, I cannot walk up the stairs anymore, I just stay here in the living room and in the kitchen, Amy comes twice a month to clean up for me, she is a nice young woman, lives three blocks away. And your husband’s study, was it upstairs? Yes, his study was that small room on the right, I don’t think I’ve ever been in there since he passed away. His library and manuscripts are still there? I asked. Oh no, she said, he never had any books. I couldn’t believe that. Really, not a single book? She nodded.

I think I spent at least an hour just sitting in that room, drifting away. It was empty. No pictures, no papers, no clothes, nothing. I silently checked all the drawers in the writing table, opened the closet, kneeled to look under the couch, it was all empty. He had nothing. He just sat there thinking, and this hollow room was the only remaining record of his thoughts. Something clicked in my head then.

What if he swallowed the world and expectorated it back exactly as it was before? What if every single particle of matter was now a concept of his? A thought so general that it coincides with the world as it is. A savage thought in which everything coexists without either a sequence or a hierarchy. And being outside of that thought?

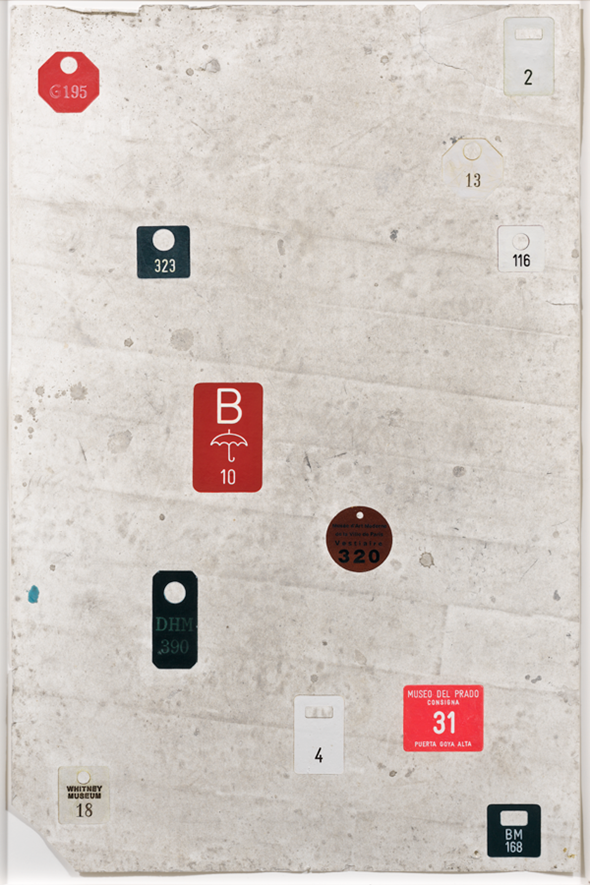

Dust and enamel on paper in artist's frame

This reminds me of Paul Sietsema’s philosophy.

(Sometimes I am not even sure which memory comes first – the bespectacled philosopher’s ghost or Sietsema’s thought textures. They seem to form a perfect palindrome. )

1) All the material structures and all the mental structures are completely interchangeable. This is the first and fundamental principle of Sietsema’s thinking. It is crucial not to reduce this statement to any kind of overreaching materialism or idealism. There are ideas and there are things – but the border between the two is completely fluid. A material object can easily become a real thought, just as an idea might modify and articulate routes, but let’s take one example: a metaphor. If we start thinking of metaphors as real transport (rather than an embellishment of speech) we can see that, for instance, each architectural element of a house (floor, ceiling, door, or window) has developed into a corresponding cluster of figurative, narrative and moral ideas (»debt-ceiling«, »pillars of society«) which give actual shape to perception. Or, to use a fleshier historical example, there is a metaphorical arch that links Harvey’s early 17th century discovery of the cardiovascular system with the development of an abstract idea of a closed circulatory system and then again with the transformation of Western European cities into vast flowing networks of coalescing roads. This leads us to Sietsema’s second principle:

2) Equality. All things and ideas might differ in their intensities and levels of relevance, but there is no essential hierarchy among them. Numbers, for example. All things can be quantified and in this respect arithmetic becomes the general structure of reality, which punctuates and orders the entirety of things. On the other hand, arithmetic itself is a single discipline with a limited set of premises and a particular history: It can itself be reified and reduced to other domains like culture or politics. In general, every single thing can be a general rule, a principle structuring reality, and a particular, limited entity. This not only goes for concepts, but also for material things: a piece of hand-woven rope is a concentrate that embodies a certain economy, social stratification, topography, or imagination. Now this draws us to the next point which can be flagged by a timeless question: What is an object?

3) An object is an aggregate of all the registers it cumulates and embodies. So for instance a ship is: a system of economic exchange, an idea of distance, a musical score, a narrative device, a disease, a way of making pictures, levitation, optics, otherness, innovation, a storm, a feeling, or a way of measuring weight. Furthermore, this list can be thickened as follows: A ship is not within economy, but rather is a body of economy; a ship is not within a story, but rather is the actual architecture of the story. Yes, this is where Sietsema’s thinking gets a bit complicated. Even more complicated because its extreme complexity coincides with its extreme simplicity: a ship is a bare existing thing and at the same time an infinitely complex being that slides out of any particular context, perspective, image or time.

Which brings us back to the empty room.

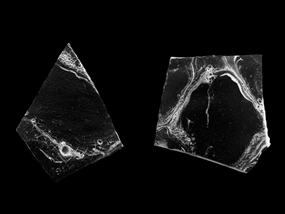

16mm film, silent, approx. 25 min

Installation view Cubitt Gallery, London 2010

II

I’ve only talked to Sietsema once.

It happened in Amsterdam some months ago. Having heard rumours about the obsessive research Sietsema was doing for his film projects (like supposedly digesting all the available anthropological data on the South Pacific tribes and then spending years weaving nets and making pots in his studio only to film and destroy them afterwards), I felt slightly uncomfortable waiting for him in a bar with a glass of beer in hand. I was sure that I would immediately recognise him when he came through the door simply due to his phrenological superiority.

Nothing like that happened of course, Paul appeared to be a laid back guy of average human complexion, a bit like Robert Smithson impersonating the archetype of an LA-artist in West Coast East Coast (1969), but with a richer vocabulary. I remember we ended up talking a lot about David Foster Wallace that night. Paul told me that Wallace was a huge inspiration for him back in the mid-90s when he was just starting out with his work at UCLA. I guess LA has never been a mecca for history-oriented art, but when Paul started getting more and more interested in the ways historical reality is represented and started treating these modes of representation as the medium of his own work, people around him in the art school became more and more certain that he was taking classes in the wrong department. But then reading Wallace put things into perspective. I didn’t really get the Sietsema/Wallace link immediately (especially given that we jumped from beer to vodka in another bar), but now that I think of it, it makes sense.

As a writer David Foster Wallace dissected all the possible protocols, technologies, media and institutions (both mental and brick-built) which channelled language in the world around him. Without trying to he would, for instance, unveil how the mass-media »constructs« the Self, or how a given technology determines what can be communicated through it. Wallace was not about deconstruction either. I think what he was actually trying to do was understand the whole complex picture of what it meant to exist and experience something in a world where every single thing is always already connected with a myriad of representations of itself, where any moment in time is simultaneously experienced through different points of view (oftentimes by the same individual) and where you can remain pretty desperate and clueless about what it all means. And I think to a large extent that is what Sietsema is trying to do as an artist as well, just without the existential anxieties so dear to Wallace.

16mm film, black and white, silent, approx. 25 min

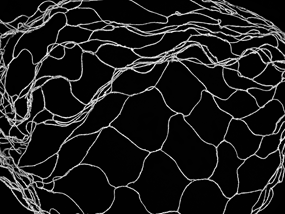

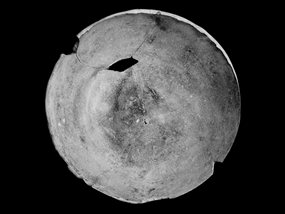

Figure 3 (2008) was the first piece by Sietsema I came across. Structurally the film is pretty straightforward: it’s a looped 16mm projection, B/W, with silent images that steadily change every couple of seconds. If it wasn’t for the projector purring beside you, you’d probably think it was a slideshow. At first glance what’s happening on the screen seems to be a kind of a Rorschach test, the images seem to be zoomed in on something that could equally well be fragments of abstract paintings, debris from a plane crash, or natural formations like rocks or fossils. You can almost feel your cognitive apparatus lassoing in the dark. Then slowly these images start to mingle with clearer ones, you start discerning round shapes that look like ancient plates pieced together from broken fragments, then some pots, details of ropes and nets, then some ancient coins and spoons. As the film progresses, it turns into something like an archaeological presentation of various artefacts excavated from somewhere deep and far. But then again when the camera zooms in, you start seeing amebae, corals, Mirós and planets. This is what glues you to this projection: It’s neither the things you actually see on the screen, nor the things you recognise or imagine, but the weird magnetic field between these two poles. As if some new object would be moulded in real-time by your mind fusing with the images.

16mm film, black and white, silent, approx. 25 min

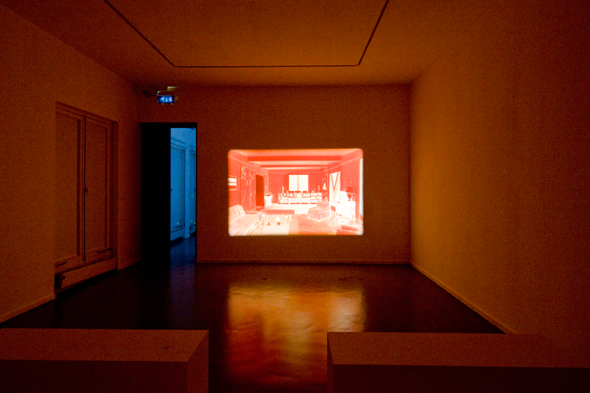

Empire (2002) is Sietsema’s other major film project which I keep watching, even if I still don’t get a large part of the things that happen there. It starts in a similar way: you see some unidentified B/W objects slowly emerging out of the black screen and then suddenly disappearing as soon as you look at them in full brightness, as if you get the after-image first and the thing itself second. Then the camera starts circling around something that could be a surface of a grotto, a detail of a modernist sculpture, or a mountain – it is impossible to determine the scale. These images are followed by hallucinatory rhomboid shapes coming in and out of focus, a couple of seconds later three orange stripes fill the whole screen. As the camera slowly zooms out you realise that these stripes are actually a detail of a large-scale abstract painting that (the camera keeps zooming out) is hanging on a wall in a richly decorated living room. This orange-filtered shot of the canvas appearing within a room is repeated again and again, until you once more start losing a sense of scale. It feels as if the whole room is turning into a painting, nothing but a flat composition of surfaces and colours.

16mm film, black and white, silent, modified projector, approx. 24 min

Installations view at de Appel, Amsterdam

The room in Empire is Clement Greenberg’s living room, or to be more precise, a model of it reconstructed by Sietsema from a photograph. The iconic canvasses wallpapering the living space of this power critic of American avant-garde seem to form a single body (with Barnett Newman at centre). It’s hard to pin it down, but it feels like there is a single line of thought running through the paintings and all the objects in the room – as if there were a mental space in which everything was interchangeable. The space within a painting = the corporeal space = the space of the mind. As in Figure 3, everything becomes so condensed that it’s hard to discern between the act of looking and the things themselves.

But I guess (this article is coming to a very abrupt ending, a train wreck almost) this is what Sietsema engineers: when things are condensed into a single body together with their histories, cultures and representations, you slowly find yourself thinking about them in a new field. Paradoxically, a field without any determined shape or history.

PAUL SIETSEMA, born in 1968 in Los Angeles. Lives in Los Angeles. Recent exhibitions include Anticultural Positions, Midway Contemporary Art (solo); Matthew Marks Gallery, New York (solo); Drawn from Photography, The Drawing Center, New York (2011); The Artist’s Museum, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Anticultural Positions, Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin (solo)(2010); The Museum of Modern Art, New York (solo); Against Interpretation, Studio Voltaire, London (2009); Life on Mars: 55th Carnegie International, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh (2008). Represented by Matthew Marks, New York/Los Angeles

JONAS ŽAKAITIS is co-director of Tulips & Roses gallery, Brussels.

16mm film, black and white, silent, modified projector, approx 24 min