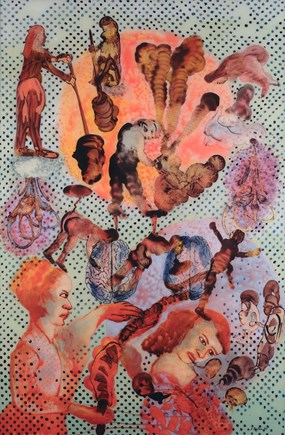

Remembering Toba Tek Singh, 1998

»A fully-grown menstruating Alice is something Lewis Carroll couldn’t have dealt with«

With her paintings and multimedia installations NALINI MALANI is one of the most prominent protagonists of Indian contemporary art. JULIA PEYTON-JONES and HANS ULRICH OBRIST speak with the artist about painting, Bert Brecht and the political in art.

Julia Peyton-Jones Do you take your inspiration from India or from the things you experience when you move outside India?

Nalini Malani Some of the sources are Indian. Kalighat painting is an important source and from literature some of the epics and stories called the Bhagavat Puranas – these are stories about the different incarnations of the Lord Vishnu, which are hilarious. I take a lot from that, especially now when things are moving towards Hindu fundamentalism, then there is all the more reason to come back to the playfulness that exists in Hinduism. The fundamentalists are trying to make edicts and »talibanise« Hinduism, as such. So it is very important to bring back into the whole Hindu epic situation the playfulness that it has had for many, many years. It has been the prerogative of the artist to transform myths, as it has been their prerogative to draw the faces and figures of the gods.

Hans Ulrich Obrist What is Kalighat painting?

NM As you can imagine, during British rule in India many of the patrons of the arts, that is the kings and nawabs etc, were quite impoverished and could not patronise miniature painting in the classical sense, so many of the artists had to find other ways and means to earn a living. One way to do this was to have little spaces around temples and make quick watercolours of the goddess [Kali] for the devotees. These were sold for one sixteenth of a rupee. At that time sixteen annas made a rupee and for one anna you could buy such a painting. As there was a lot of free time in between, the artists tried to capture some of the social aspects of the region, almost in the form of comic strip pictures. I suppose the exigency of the situation really gave rise to a new kind of form. The exigency was, firstly impoverishment, secondly, the need to keenly observe what was around them. And thirdly, the import of watercolours, Winsor and Newton. That made a lot of difference. Watercolour spread more easily than the traditional tempera colours. It lent itself to the quick brush stroke.

HUO And what was it that inspired you with Kalighat?

NM It was several things: the history interested me very much. I think that this was really the cutting edge of modernism in Indian art in the way the figure was drawn or rather painted. The figures had a very shallow shadow, much like Léger, and we always say in India, »I am sure Léger saw Kalighat paintings«. (Laughs)

HUO Can you talk a little bit about India as a multicultural society and about your own cultural background, your childhood and the Partition?

NM A lot of it is from the stories my parents and grandparents told me. I was born in 1946 and we fled in that same year. My parents had to flee with just the clothes on their backs. It’s the same old story. There was always nostalgia for the homeland. Even today my mother speaks about her town, Hyderabad, Sindh, and how it was laid out. If anybody comes from Pakistan she always asks, »Does such a thing exist? Is the bazaar still there? Is that shop there?« So there is a lot of nostalgia and yearning because it was a place where they spoke the Sindhi language, which is my mother tongue.

JP-J Your parents were refugees from Karachi the year you were born so do you feel absolutely Indian?

NM Yes, absolutely Indian, but there are many Indias. We moved from Karachi to Calcutta. There my father joined Air India and my mother started to do a lot of rehabilitation work for the refugees from East Bengal because there as well there was a partition and she seemed to have an affinity to those refugees because that was the only way she could get over her yearning.

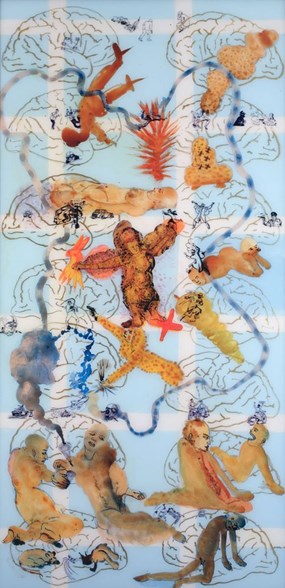

Medea III, 2006

HUO Once we spoke about your heroes you also mentioned Western heroes. I was particularly intrigued to hear about Heiner Müller and Christa Wolf.

NM Christa Wolf, I am just going to start work now on one of her texts. Regarding Heiner Müller, there is a performing artist of Indian origin who lives in London, Alaknanda Samarth. She and I have known each other for several years. I made an installation where the entire gallery had wall drawings titled City of Desires. She walked into it and she started to do things. There was pigment on the floor and other objects. »This invites performance«, she said. »Let’s do something from the start«. And I loved that. And then she gave me the text of Medeamaterial by Heiner Müller and that for me was it – it was terrific! I just loved the melding of classical language with the noise and scratch of graffiti.

JP-J Is all your work in watercolour?

NM No. I also do the old technique of reverse painting on glass. Glass painting is really not a high art, it is on the cusp of high and low. It came to India with the Chinese in the fourteenth century and it came as pornographic images on little pieces of glass, which were sold at the harbour. In the South artists seemed to like the technique very much and they turned the profane into sacred and now you can buy images of gods and goddesses in glass painting embedded with jewellery and stuff like that. In parts of the North and West it’s used as decoration for wardrobes, as insets for cupboards, for headboards and things like that, so it’s not a very high art.

HUO And you also paint directly on the wall?

NM Yes. Those are completely ephemeral, they get whitewashed afterwards. These are works to remember – to recall as in a performance.

HUO Do you draw?

NM Yes. I’ll show you some watercolour drawings … They are about »listening«. My next project with Alaknanda is on the subject of Cassandra, and Cassandra is about listening. These that you see here are from the series titled Living in Alicetime, a take on Lewis Carroll’s Alice. But a fully-grown menstruating Alice is something Lewis Carroll couldn’t have dealt with, I think.

HUO And what about the Transgressions? There are the wall paintings, there are your reverse paintings and there are also the Transgressions where you really do spaces. Can you talk about those?

NM I have done transparent cylinders. It is reverse painting, but I leave it transparent so that with the help of a light it casts seamless moving shadows. I have done lots of shadow plays. It started actually with theatre when I was doing Bertolt Brecht’s The Job, which is an adaptation from a short story. There is a lot of Bertolt Brecht here. Everything is translated, in Bengali especially.

HUO Why, do you think?

NM Somehow it is so good for the sensibility in Bengal where it’s a Communist government and they feel very close to that text. They actually have it as a travelling theatre through the villages. As a Yatra. I have seen Mother Courage and Caucasian Chalk Circle. People love it. They just come in the village square and they perform.

HUO And what have you done regarding Bertolt Brecht’s work?

NM There is a short story from 1923 called, The Job or By the Sweat of Thy Brow Thou shalt fail to Earn thy Bread. It’s about a woman who impersonates her husband, who has died. There was a lack of jobs, of course, in Germany at this time. I can’t quite remember but it seems as if he had read this in a newspaper article and then transformed it into a short story. I worked with a theatre director, Anuradha Kapur, and we made it into a play with one performer. I made these cylinders one metre fifty high, which was the actor’s height. The theatre had a ceiling of about 10 meters. I had five such cylinders going over her, as each went over her she was transformed. I don’t know if you have ever played with paper dolls as a child. It took off from the paper doll concept. When these cylinders came down slowly from the flies that were 10 meters high they started to twirl and cast shadows. The actress played havoc with us as she refused to travel this piece. We were quite distraught. It was then that I thought of making the shadow play. (Laughs)

HUO That’s how you invented it.

NM Yes. (Laughs)

NM Christa Wolf, I am just going to start work now on one of her texts. Regarding Heiner Müller, there is a performing artist of Indian origin who lives in London, Alaknanda Samarth. She and I have known each other for several years. I made an installation where the entire gallery had wall drawings titled City of Desires. She walked into it and she started to do things. There was pigment on the floor and other objects. »This invites performance«, she said. »Let’s do something from the start«. And I loved that. And then she gave me the text of Medeamaterial by Heiner Müller and that for me was it – it was terrific! I just loved the melding of classical language with the noise and scratch of graffiti.

JP-J Is all your work in watercolour?

NM No. I also do the old technique of reverse painting on glass. Glass painting is really not a high art, it is on the cusp of high and low. It came to India with the Chinese in the fourteenth century and it came as pornographic images on little pieces of glass, which were sold at the harbour. In the South artists seemed to like the technique very much and they turned the profane into sacred and now you can buy images of gods and goddesses in glass painting embedded with jewellery and stuff like that. In parts of the North and West it’s used as decoration for wardrobes, as insets for cupboards, for headboards and things like that, so it’s not a very high art.

HUO And you also paint directly on the wall?

NM Yes. Those are completely ephemeral, they get whitewashed afterwards. These are works to remember – to recall as in a performance.

HUO Do you draw?

NM Yes. I’ll show you some watercolour drawings … They are about »listening«. My next project with Alaknanda is on the subject of Cassandra, and Cassandra is about listening. These that you see here are from the series titled Living in Alicetime, a take on Lewis Carroll’s Alice. But a fully-grown menstruating Alice is something Lewis Carroll couldn’t have dealt with, I think.

HUO And what about the Transgressions? There are the wall paintings, there are your reverse paintings and there are also the Transgressions where you really do spaces. Can you talk about those?

NM I have done transparent cylinders. It is reverse painting, but I leave it transparent so that with the help of a light it casts seamless moving shadows. I have done lots of shadow plays. It started actually with theatre when I was doing Bertolt Brecht’s The Job, which is an adaptation from a short story. There is a lot of Bertolt Brecht here. Everything is translated, in Bengali especially.

HUO Why, do you think?

NM Somehow it is so good for the sensibility in Bengal where it’s a Communist government and they feel very close to that text. They actually have it as a travelling theatre through the villages. As a Yatra. I have seen Mother Courage and Caucasian Chalk Circle. People love it. They just come in the village square and they perform.

HUO And what have you done regarding Bertolt Brecht’s work?

NM There is a short story from 1923 called, The Job or By the Sweat of Thy Brow Thou shalt fail to Earn thy Bread. It’s about a woman who impersonates her husband, who has died. There was a lack of jobs, of course, in Germany at this time. I can’t quite remember but it seems as if he had read this in a newspaper article and then transformed it into a short story. I worked with a theatre director, Anuradha Kapur, and we made it into a play with one performer. I made these cylinders one metre fifty high, which was the actor’s height. The theatre had a ceiling of about 10 meters. I had five such cylinders going over her, as each went over her she was transformed. I don’t know if you have ever played with paper dolls as a child. It took off from the paper doll concept. When these cylinders came down slowly from the flies that were 10 meters high they started to twirl and cast shadows. The actress played havoc with us as she refused to travel this piece. We were quite distraught. It was then that I thought of making the shadow play. (Laughs)

HUO That’s how you invented it.

NM Yes. (Laughs)

Medea I, 2006

HUO When did you start to use video?

NM I used video in Medeamaterial in 1993 and then in ’98 I made my first video installation. It was after India tested a nuclear device and was called Remembering Toba Tek Singh, a four-channel work with sound and 12 monitors. This work too had a sense of the theatre. It was based on a short story by an Indo-Pakistani writer, Sa’adat Hasan Manto, a brilliant writer of short stories. It’s a story everyone knows in India as well as in Pakistan. The work was a critique against the nuclear testing that both countries had done, more to show off their so-called power. Such a bad idea. But of course everyone was euphoric about it. National pride was at a high. I showed it at the Prince of Wales Museum – a very popular museum for Indian tourists. Three thousand people came every day. It created quite a debate as people argued and shouted at me. The Museum allowed me to show the work for only 10 days. I was there every day.

HUO So do you consider yourself to be a political artist?

NM Come on, Hans Ulrich! You can’t ask me this question. (Laughs)

HUO I think to some extent this whole idea of the political artist is coming back.

NM Even if you don’t want to do anything with politics it has a lot to do with you, whether you like it or not.

JP-J All art is political. But there are extreme versions of political art, which are perhaps the subject matter and the driving force to make art and that is a slightly different emphasis.

NM Yes. Well, I am not interested in propaganda, nor am I interested in didacticism, nor am I interested in posters, but in my own fashion I like to speak about it. That is the only tool I have.

HUO I was thinking Brecht brings us to politics.

NM Right. Well, you know I’ve been reading Luce Irigaray and you can see already she speaks of the difference in the language of the male and female. It is now time to pay close attention to female subjectivity if anything called progress is to be achieved. That’s my interest. Religious fundamentalism prescribes the subjugation of women. It is women who must wear the accoutrements of religion. It is they who are accused of using their sex to excite the male and hence must be covered from head to foot.

JP-J I want just to return to the idea of Bert Brecht again because it’s such an incredibly vivid idea that these players would literally arrive in the village square and begin to perform. I think of Shakespeare, of course, whereby the story of humankind is common to all and that is really why it has an audience. And that is really, perhaps, why Bert Brecht continues to live in a much stronger way now than it did perhaps a decade ago. In the stories you depict you feel that real link for speaking for the man in the street, speaking to all, so that your audience is a very wide one. It is humankind rather than a particular group. Is the audience important for you?

NM Audience is very important. This is the reason why I actually started to make video; it was really to appeal to a larger audience and be able to show videos in spaces that were not white cube spaces. You must notice if you go into galleries over here, it’s a daunting space for the man in the street. They don’t walk in.

JP-J Difficult, I may say, everywhere.

NM Yes, but here more than anywhere else. Whereas the Prince of Wales Museum is a place for people so people walk in. They come in buses from other parts of the country and they feel this is part of the tourism that is acceptable and allowed. So this is one reason why video is so important

for me.

HUO So what is your vision for the museum of the twenty-first century? It is not necessarily the case that the same museum that is right for Europe is right for India. In China it’s the same. It’s a sort of homogenised standard.

NM I think we are not using radio and television enough. In fact, some of the single channel works that we have been making should really be shown on television. I think that is the way really to reach the public, and the Internet.

HUO So the museum should be television.

NM Television, Internet and streaming on the streets, video graffiti. Shilpa [Gupta] has done some of that. And the city festivals do a lot on the street.

HUO To come back to the museum as a museum, if it is not a white cube, how would the museum work?

NM I am not against museums, to tell you the truth. I think they are great areas of learning. We lack such museums here therefore I feel there is a huge need for museums in our country. We do not have them, they are shut. As you see, the National Gallery is shut, it’s a mausoleum. There have been art movements prior to Independence like the Bengal School and the Shantiniketan Schoolk, which the younger generation don’t even know about, have never even seen in the flesh. I just feel it’s such a pity that they have no background to go to, no reproductions either. So how do you trace your history? That’s why I think the museum is important. But if you are talking about what we are doing now and how we are going to get art to a wider public, I think we need to have something that Singapore has – shopping malls. (Laughs) That’s another way. I’ve seen people imbibing art quite unconsciously through shopping mall culture.

HUO I was wondering if you have ever worked with public art and if you had any kind of unrealised projects.

NM Well yes. When I did wall drawings at the gallery it was in front of people; people could come and go and they could even make comments. It’s like in certain tribal societies over here; you start to make murals on the side of your hut and everybody passes by and says, »This is not quite right«, »That is not right«. »Do it like this«. And you incorporate it all and try to do an interactive thing with the people. And that’s quite nice to do

HUO And what is your utopia? Do you have a dream?

NM Yes. (Laughs) To do a theatre performance out in the open air in an old car park.

JULIA PEYTON-JONES is director at the Serpentine Gallery in London. HANS ULRICH OBRIST is Co-Director for Exhibitions and Programmes and Director of International Projects at the Serpentine Gallery in London.

NALINI MALANI, born in 1946 in Karachi, Pakistan. Lives in Mumbai. Numerous international exhibitions including Sidney Biennial (2008); Irish Museum Of Modern Art, Dublin (2007); Living in Alicetime, Sakshi Gallery, Bombay und Rabindra Bhawan, New Delhi (2006); T1 The Pantagruel Syndrome, Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Torino; Biennale di Venezia (2005), Sharjah Biennial (2005)

Represented by Arario Gallery, New York, Bodhi Art Gallery, Mumbai, New York, Berlin, Singapore

NM I used video in Medeamaterial in 1993 and then in ’98 I made my first video installation. It was after India tested a nuclear device and was called Remembering Toba Tek Singh, a four-channel work with sound and 12 monitors. This work too had a sense of the theatre. It was based on a short story by an Indo-Pakistani writer, Sa’adat Hasan Manto, a brilliant writer of short stories. It’s a story everyone knows in India as well as in Pakistan. The work was a critique against the nuclear testing that both countries had done, more to show off their so-called power. Such a bad idea. But of course everyone was euphoric about it. National pride was at a high. I showed it at the Prince of Wales Museum – a very popular museum for Indian tourists. Three thousand people came every day. It created quite a debate as people argued and shouted at me. The Museum allowed me to show the work for only 10 days. I was there every day.

HUO So do you consider yourself to be a political artist?

NM Come on, Hans Ulrich! You can’t ask me this question. (Laughs)

HUO I think to some extent this whole idea of the political artist is coming back.

NM Even if you don’t want to do anything with politics it has a lot to do with you, whether you like it or not.

JP-J All art is political. But there are extreme versions of political art, which are perhaps the subject matter and the driving force to make art and that is a slightly different emphasis.

NM Yes. Well, I am not interested in propaganda, nor am I interested in didacticism, nor am I interested in posters, but in my own fashion I like to speak about it. That is the only tool I have.

HUO I was thinking Brecht brings us to politics.

NM Right. Well, you know I’ve been reading Luce Irigaray and you can see already she speaks of the difference in the language of the male and female. It is now time to pay close attention to female subjectivity if anything called progress is to be achieved. That’s my interest. Religious fundamentalism prescribes the subjugation of women. It is women who must wear the accoutrements of religion. It is they who are accused of using their sex to excite the male and hence must be covered from head to foot.

JP-J I want just to return to the idea of Bert Brecht again because it’s such an incredibly vivid idea that these players would literally arrive in the village square and begin to perform. I think of Shakespeare, of course, whereby the story of humankind is common to all and that is really why it has an audience. And that is really, perhaps, why Bert Brecht continues to live in a much stronger way now than it did perhaps a decade ago. In the stories you depict you feel that real link for speaking for the man in the street, speaking to all, so that your audience is a very wide one. It is humankind rather than a particular group. Is the audience important for you?

NM Audience is very important. This is the reason why I actually started to make video; it was really to appeal to a larger audience and be able to show videos in spaces that were not white cube spaces. You must notice if you go into galleries over here, it’s a daunting space for the man in the street. They don’t walk in.

JP-J Difficult, I may say, everywhere.

NM Yes, but here more than anywhere else. Whereas the Prince of Wales Museum is a place for people so people walk in. They come in buses from other parts of the country and they feel this is part of the tourism that is acceptable and allowed. So this is one reason why video is so important

for me.

HUO So what is your vision for the museum of the twenty-first century? It is not necessarily the case that the same museum that is right for Europe is right for India. In China it’s the same. It’s a sort of homogenised standard.

NM I think we are not using radio and television enough. In fact, some of the single channel works that we have been making should really be shown on television. I think that is the way really to reach the public, and the Internet.

HUO So the museum should be television.

NM Television, Internet and streaming on the streets, video graffiti. Shilpa [Gupta] has done some of that. And the city festivals do a lot on the street.

HUO To come back to the museum as a museum, if it is not a white cube, how would the museum work?

NM I am not against museums, to tell you the truth. I think they are great areas of learning. We lack such museums here therefore I feel there is a huge need for museums in our country. We do not have them, they are shut. As you see, the National Gallery is shut, it’s a mausoleum. There have been art movements prior to Independence like the Bengal School and the Shantiniketan Schoolk, which the younger generation don’t even know about, have never even seen in the flesh. I just feel it’s such a pity that they have no background to go to, no reproductions either. So how do you trace your history? That’s why I think the museum is important. But if you are talking about what we are doing now and how we are going to get art to a wider public, I think we need to have something that Singapore has – shopping malls. (Laughs) That’s another way. I’ve seen people imbibing art quite unconsciously through shopping mall culture.

HUO I was wondering if you have ever worked with public art and if you had any kind of unrealised projects.

NM Well yes. When I did wall drawings at the gallery it was in front of people; people could come and go and they could even make comments. It’s like in certain tribal societies over here; you start to make murals on the side of your hut and everybody passes by and says, »This is not quite right«, »That is not right«. »Do it like this«. And you incorporate it all and try to do an interactive thing with the people. And that’s quite nice to do

HUO And what is your utopia? Do you have a dream?

NM Yes. (Laughs) To do a theatre performance out in the open air in an old car park.

JULIA PEYTON-JONES is director at the Serpentine Gallery in London. HANS ULRICH OBRIST is Co-Director for Exhibitions and Programmes and Director of International Projects at the Serpentine Gallery in London.

NALINI MALANI, born in 1946 in Karachi, Pakistan. Lives in Mumbai. Numerous international exhibitions including Sidney Biennial (2008); Irish Museum Of Modern Art, Dublin (2007); Living in Alicetime, Sakshi Gallery, Bombay und Rabindra Bhawan, New Delhi (2006); T1 The Pantagruel Syndrome, Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Torino; Biennale di Venezia (2005), Sharjah Biennial (2005)

Represented by Arario Gallery, New York, Bodhi Art Gallery, Mumbai, New York, Berlin, Singapore

Stories Retold: Mapping II, 2007