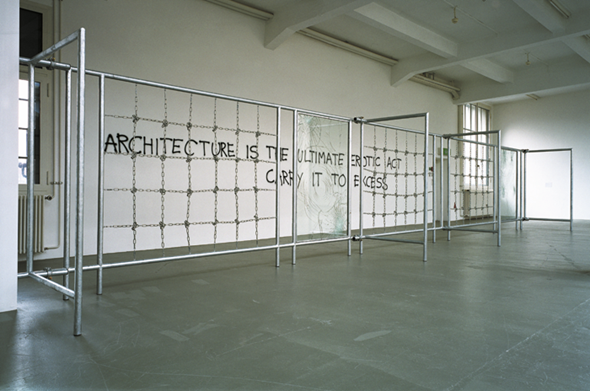

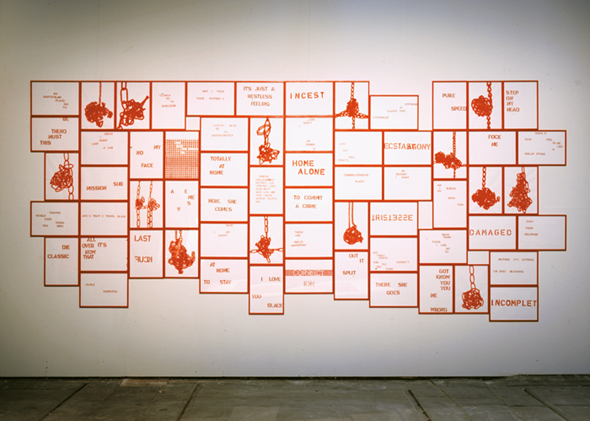

Art as Architectural Critique: MONICA BONVICINI’s installations of chains, metal bars and glass boxes are an attack on the phallocentrism and latent violence of modernist concepts of ordering and planning. In this interview with JENNIFER ALLEN the artist talks about the relationship between architecture and sexuality and dismantles some of the myths surrounding her work.

Jennifer Allen: What is a building for you?

Monica Bonvicini: A building is a container, something that acts as a barrier and stays in your way. Actually, it would be nice not to have any buildings. When I walk down the street at night and look into the apartments with the cosy lights on inside, a feeling of disgust hits me. Of course, one cannot live without buildings. And disgust is a very personal reaction. At the same time, a building stands for a culture, a time, a style – for power … I don’t like buildings in general. Architecture is different. Architecture is more like a theoretical object, a theory with several points of entry.

Sexuality seems to be a point of entry in your approach to architecture, whether one considers the early work Wallfuckin’ (1995/96), where a woman rubs herself against a wall, or Pavilion (2002), which puts an S&M seat into a frame that matches the size of Le Corbusier’s minimum living space.

You seem to adopt a Freudian approach to built space: Does all architecture have to do with sexuality?

Yes and no. Every space has a character that makes each person react in a different way. I am sensitive about the way spaces create these kinds of reactions. Everyone can make the associations they can make … For me, sexuality is a way to express ironically and recklessly what I want to say about issues that I might not be able to talk about in another way. There is something basic, and still very complex, in sexuality that I found in architecture, too.Wallfuckin’ or The Fetishism of Commodities (2002), are installations that deal with sexuality, yet they do so with an ‘I don’t give a fuck’ attitude towards big structures like theory and architecture. With its metal, chains and leather, The Fetishism of Commodities confronts Marx’s ideas about labour with architects’ fetishism for pure materials and an S&M sexuality, which is about power relations. Since you mentioned Freud, everybody has a sexual drive; sexuality is with you all the time, however it is expressed. That said, I don’t want to put buildings on a couch. Along with reading, I analyse a work to decide what is more important and what is not as an art work. But if you deal with sculpture and large-scale installation, then you have to relate to the body first, and sexuality is part of it.

You seem to create a fluid, living architecture where the walls are ‘built’ by the viewer.

Yes and no. I am interested in creating a space or situations that are very precise and determined, to present a philosophical as well as a physical structure where you can act. Normally, people have a lot of respect for art, and, in some ways, I want to demystify the aura that is still around it, despite all the attempts that have been made to break it. At the same time, I think art is there to think, to make connections you wouldn’t have thought of otherwise… ‘What you see is what you see,’ but what do you see? In terms of architecture’s aura, let’s take glass and the connected idea of transparency and, with it, democracy. Broken glass has become a recurrent material in my recent work, although I am the one doing the breaking – and for the record, I don’t shoot at the glass with a gun to make cracks and holes, as has been reported; I smash them with a hammer! Stonewall (2001), was the first piece that incorporated broken glass. I did it shortly after the riots during the G8 summit at Genoa, which was gated off to the public. I was also thinking about Cady Noland’s gates and public architecture with its accessibility and its monumentality as a State-related power symbol. I wanted to show that even if you have a gate in front of you, that doesn’t mean that you can’t do something with it or something to change it. Stairway to Hell (2003), was my work for the last Istanbul biennial: a glass pavilion set at the top of a free standing staircase, which was supported and enclosed by chains. When people walked up the stairs through the chains and saw the glass above, they may have thought about transparency or freedom. But since the glass was broken, viewers couldn’t clearly see the whole space on the upper floor surrounding the staircase, nor the art works hanging there. The whole experience of walking up the stairs was sort of disturbing.

Your resistance to site seems to critique both art and architecture, since architects often design in relation to site. How do the two practices come together for you, especially in light of the last decade, which saw architects and artists exchanging roles?

I find the works of artists doing architecture more interesting than the other way around. There’s constant conflict between the two professions since architects understand themselves as the biggest artists – maybe because they make big things. Artists are not under such financial and political pressure; they can deal with issues that architects don’t have the time nor the frame of mind to address. I have been working with architects, and I was at different symposiums on the relation between architecture and art. But I always have the feeling that even if the two fields are very close, artists and architects still speak two different languages… Architects often quote art works, their aesthetic and form; artists dealing with architecture are more interested in the idea and the possibility of architecture, not in its materiality or size. The good thing about being an artist is that you cannot hurt anybody; if the work is bad, you may add some stupidity to the general pre-existing stupidity (which is already bad enough). But architects, as we all know, can do damage that has a much longer life…

JENNIFER ALLEN is editor of frieze d/e and lives in Berlin.

MONICA BONVICINI born in 1965 in Venice, Italy, lives in Berlin. Since 2003 professorship at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna.