What does a performance look like without an eye on media friendly, marketable secondary use, or without pathos and self- revelation? Is it possible to translate knowledge into movement and the body? DANIEL BAUMANN on EI ARAKAWA and the anarchistic attempt to create a picture of contemporary life beyond images and representation.

Consider this: around the end of the 70s and the beginning of the 80s a great shift took place in art from thought to object; its effects are still with us today and suffered a slight reverse with the current financial crisis. This shift was the expression and the consequence of an economic up-swing and, running parallel to that, a weakening of the ideologies that determined the post-war order. It had its first climax in the multifaceted discourse and publicity work around postmodernism and the universal availability of history, and in the everyday it took the form of a kind of hedonism borne by the feeling that »anything goes«. Suddenly history seemed to be accessible and negotiable in a new way and the first post-war generation began to claim heuristic and economic power. »Wilde Malerei« (Wild Painting) and Neo Geo drove the market forward; Joseph Beuys, the priest of the other capital, died in 1986 and in October 1987, Wall Street had its first big Crash. On top of this came the criticism from within, the criticism of Concept Art, its dominance and its limits. Even today, in relation to Jeff Wall’s analysis and final reckoning with Concept Art published in 1985, it reads like a crime story. Think of such formulations as, »What is unique about conceptual art is therefore its reinvention of defeatism, of the indifference always implicit in puristic and formalistic art.« His two-part article appeared in the American Real Life Magazine, which accompanied, discussed and documented the Pictures Generation from close quarters.* Their work more than others can be understood as an attempt to set both spheres into an insoluble tension, in other words the world of the concept and dematerialisation with that of the powerful and seductive object.

The only art practice that would have been able to escape the curse of the object would have been performance art: its business has been and is still today the ephemeral translation of thoughts into bodies, time and space. The problem, however, was that it was trapped in the pathos of self-revelation and in the 90s primarily concerned with translating this language into the video medium in order to solidify it and make it marketable. And then surprises occurred. In 2005 I asked Emily Sundblad or rather Reena Spaulings for a contribution to Wednesday Calls the Future, an exhibition in Tbilisi, Georgia. She mailed me the scenario for a performance originally planned to be shown under the title Grand Openings in November on the occasion of the Performa05 festival in New York and which had been developed jointly by Ei Arakawa, Jutta Koether and Emily Sundblad. We produced it as a kind of pre-premiere in Georgia. Everyone took on a role: Mai-Thu Perret was, for example, Jutta Koether, if I remember correctly. Such details seem redundant and anecdotal, but they are not, because they make it clear that Grand Openings broke with the idea of performance as the exposure of an ego or of an ego figure. Grand Openings appeared to be something anyone could do. That was not everything, for what was really surprising was the performance itself, which helped me to see performance art as a medium beyond the boundaries of pathos and embarrassment. The scenario was totally incomprehensible, the individual parts had no connections, it seemed to be a senseless sequence of moments and any production of sense was passed over to the audience, with not an ego to be seen. There was only presentation, but no representation, as the Georgian art historian Nana Kipiani remarked in passing.

Ei Arakawa, a Japanese artist living in New York, is often associated with the Grand Openings project. But in his work it is an exceptional product, because it is developed by a fixed crew while dispensing with a common starting point or a defined goal. All of Arakawa’s other performance projects begin with an interest in something that triggers a moment of identification. This draws a process of greater depth behind it as well as the attempt to translate the appropriated material, bringing it closer to body and movement, in order to give it a physicality of its own.

Three examples: Don’t Think About Me, I’m Alright took place in 2004 in Greene Naftali Gallery, New York, jointly with Patricia Cazorla, Kimiko Fukuoka, Michiko Hoshi, Miki Ikeda, Mari Mukai, Etsuko Noda, Hisayasu Takashio and Maki Waza. At the beginning of the project stood an interest in the identity of the Japanese artist On Kawara and his work with Esperanto: »I was fascinated to know where he comes from and his knowledge of Esperanto, and then I tried to make a performance out of it without illustrating it, but making it physically present. I saw On Kawara as a product of Japanese post-war education, which changed very fast from extreme nationalism to liberalism. On Kawara participated in an Esperanto group too. I wrote an essay about it and made a 13 minute video piece out of. In the film, the text of my essay runs as English subtitles and at the same time you could hear a voice in Chinese pronounced by an American. The video itself was mostly a slideshow documenting various performances I did but it also shows pictures of me painting a fake On Kawara painting while sitting in an airplane. The painting says Duty Free in Esperanto (although I misspelled it) and you hear the noise of the airplane and the flight attendant saying ›Duty Free, Duty Free‹. Because On Kawara is a Duty Free artist to me. This video was made for a conference of art historians and played during the break.«

An earlier version of this was shown during the nine-hour performance at Greene Naftali. At this time Arakawa was attending an old fashioned art school in New York to get a visa for the USA. For the performance he invited eight of his fellow students to fake On Kawara’s pictures, destroy them and screw them together into a kind of constructivist structure. In addition, a copy machine in the gallery printed out interviews that Arakawa had made earlier with the students and which provided very personal information about their lives. The performance was structured according to these interviews, while the copied pages were bound together into booklets and distributed among the visitors.

In 2005, as a student at Bard College, Arakawa organised the project Riot the Bar. It was an eight-day performance that started with a visit to Stonewall, the gay bar in New York where in 1969 an uprising began against a homophobic police raid, which is commemorated by Christopher Street Day. Today Stonewall is, as Arakawa puts it, »a touristy place for the official gay scene and they opened a new space, Stonewall Bistro.« This change was documented by Arakawa for Riot the Bar in a brochure, which also included the program for the eight days. He threw a bar together with simple materials, where a lecture was held every evening. DJs performed and drinks like Buttery Nipple, Sour Apple Martini or Blow Job were served. On the first evening the artist Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, who had been an active participant in 1969, spoke about his experiences. In the outdoor area of Bard College Arakawa installed portraits of Felix Gonzalez-Torres, David Wojnarowicz and Ana Mendieta, who represented the three known identity-politics artists for him and for the project. Every evening he made a list of his takings, and if the sum was larger than on the previous evening he added new portraits of the three artists, so that in the end a whole field was covered with their faces. At the end of the performance the bar was sold by auction for $150 or $200, but it broke into pieces during transport. Two years later Arakawa produced Riot the Barfor a second time in the Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst (NGBK) in Berlin, under the title Riot the 8 Bar, for which he invited, among others, Bill Dietz, Sebastian Biskup, Andrew Smith, Nick Mauss, Ken Okiishi, Nora Schultz and Josef Strau. »In Berlin we destroyed the bar every night. It was made out of a lot of material and pedestals around to be used. The next day, we moved the bar to the next room and installed it again, or even outside, when the Kreuzberg gay parade was happening. We didn’t have the portraits like at Bard College, but again, I informed the people about the profit I was making.«

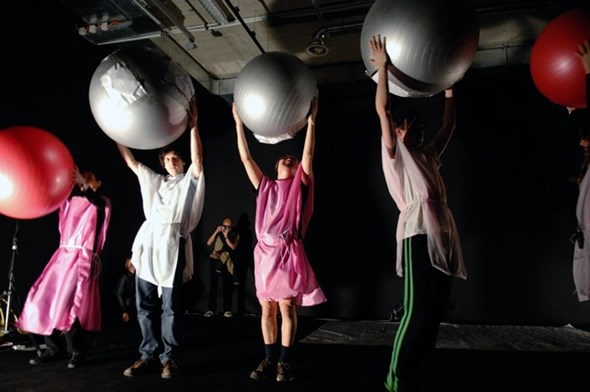

The starting point for M.A.V.O.E. (killer COMMERCIAL), the performance which took place in the exhibition space New Jerseyy in Basel in September 2009 is partly the Japanese performance group Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop), which is little known in the West, and partly Mavo, an avant-garde group around Murayama Tomoyoshi (1901–1977), who was active from 1923 to 1925. Jikken Kobo began with its actions in 1951, three years before the Gutai Group, which is believed in the West to be the founder of Japanese performance art.** From its very beginnings the collective aimed at a cross-media art practice outside all artistic and social classifications, a kind of art that went beyond art, which took place outside the museum space, was socially relevant and developed close to everyday life. The collective refused to construct a clear identity. Since it wrote no manifesto, was not anchored to any place and left no work behind, and because its actions were hardly ever documented, Jikken Kobo sank into oblivion. Like Jikken Kobo, Mavo rejected the firmly established art system in the Western style (»gadan«). Mavo developed what was called Conscious Constructivism with the aim of creating an image of modern life beyond depiction and representation, but in close contact with the everyday. For two years the Mavoists celebrated a comprehensive anarchistic aesthetic, with stage sets, plays, acrobatic performances, architectural models, exhibitions, dance, books, magazines, wall decorations, sculptures and structures. After its dissolution, Murayama became more radical, becoming a member of the Japanese Communist Party, and fighting against censorship where he was arrested again and again. He continued to pursue his ideas of a different kind of theatre and designed, for example, the covers for the Japanese theatre magazine La Teatro, which is still published today.

The story of Jikken Kobo and Mavo reads something like a portrait of Arakawa’s work. This is characterised, in the first place, by being confusing and apparently formless, constantly resulting in rejection and evoking an impression of boredom. In a different context it is part of the developments and experiments that many other artists are working on: the attempt to achieve a different kind of historiography and self-positioning with the means of art. In the process an interest in history and subjective experience is shaped in ever changing constellations into artworks that simultaneously present autonomy, historical consciousness and a commitment to their contingency. As a recipient one often faces the problem that the involvement with history is often at a modest level and that this constriction is supposed to be compensated with virtuoso design. The extension of the art market has made a lot of room for big quantities of this kind of art object, which all seem convinced of their momentousness and, in their most detached and boring variants, celebrate nothing but their own emptiness. And so today we stand in front of the objects we have called for, because we have had enough of thoughts and their illusions. And now we ask ourselves where thoughts have gone and how they can be manifested on the far side of concept art, the esoteric, idealism and market cynicism. For this reason Arakawa’s procedure interests me, even though I by no means understand it all and am not at all sure whether the translation of knowledge into physicality and movement actually works. But I do want to go along with the idea, the assertion and the experiment, for beyond success or failure these performances stand for independence from the terror of the object, for freedom and, I hope, for anarchy.

* Jeff Wall, »Dan Graham’s Kammerspiel. Part I / Part II«, Real Life Magazine, 1985, reprint in Real Life Magazine. Selected Writings and Projects 1979–1994, Primary Information, New York 2006.

** See the detailed study by Miwako Tezuka, Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop): Avant-Garde Experiments in Japanese Art of the 1950s, Columbia University, 2005.

Translated by Nelson Wattie

DANIEL BAUMANN is a freelance critic and curator. He lives in Basel, where, together with Tobias Madison, Emanuel Rossetti and Dan Solbach he runs the exhibition space New Jerseyy.

EI ARAKAWA, born in Fukushima, Japan in 1977. Lives in New York. Most recent projects, among others, Non-solo show, Non-group show (with Nikolas Gambaroff, Nick Maus and Nora Schultz ), Kunsthalle Zurich; Künstlerhaus Stuttgart; Sculpture Center, (Grand Openings), NY; New Jerseyy, Basel; Liaison, a Naïve Pacifist, Taka Ishii Gallery, Kyoto (2009); Non-solo show, Non-group show (with Henning Bohl and Nora Schultz), Franco Soffiantino Arte Contemporanea, Turin (2008). Exhibition participation include: Autocenter (with Nora Schultz), Berlin; Bulletinboard Blvd., Pro Choice (with Patrick Price), Vienna (2009); TBI LI SI 5. Wednesday was Thursday (with Sergei Tcherepnin, Gela Patashuri, and Daniel Baumann), Tbilisi, Georgia; Yokohama Triennale 2008, Kanagawa, Japan; The Altoids Award 2008, New Museum, NY; Front Room at Contemporary Art Museum, St. Louis, USA; Nichts I ST AUFREGEND. Nichts I ST S EXY. Nichts I ST NI CHT P EI NLI CH, MUMOK, (Grand Openings), Vienna (2008); Performa07, NY; Syntropia, NGBK Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst, Berlin (2007).

Represented by REENA SPAULINGS FINE ART, New York; TAKA ISHII GALLERY, Tokyo, Kyoto