Dignity

Exposure

Control

A refusal to compromise is not just common sense, and especially not when it is a matter of showing sick or mutilated people. Empathy, sensitivity, concern for the underdog, always coupled with an idea of comfort – that is our usual picture morality. But ARTUR ZMIJEWSKI has long crossed the border to the unbearable. By DANIEL BAUMANN

Karolina (2002) is an eight-minute film about 18-year-old Karolina: she is lying in bed, her bones have multiple fractures; they are fragmenting and will not grow together again. Any movement, even the tiniest, causes terrible pain. It is clear that Karolina is slowly dying. She is dependent on morphine, having decided that she needs it to quieten the unbearable pain. If it is to work, the dose has to be raised continually, which not only causes addiction but also means that her brain receives too little oxygen and the brain-cells are destroyed. The fight against pain will bring about her death.

She met the Polish artist Artur Zmijewski in response to an advertisement. Zmijewski had inserted a little notice in a Polish newspaper, looking for a person willing to share his or her pain with others. Karolina, suffering from advanced osteoporosis, rang him up. Zmijewski drove over to see her and filmed her. Karolina is an unbearable film, because there is no hope of any future. In the catalogue If it happened only once it’s as if it never happened, which accompanies both Zmijewskis current exhibition at the Kunsthalle Basel and his appearance in the Polish pavilion at this year’s Biennale, the artist is quoted as follows:

“I asked her about what happens after you die. She said nothing happens any more. I also asked her about boredom – she had been bedridden for months, lying alone in a dim room, in a flat stuffed with old furniture. She said she did not feel any boredom because pain filled her time. There was only one question I wanted to ask her, but didn’t – about sex. Is her body a source of only pain for her? Or also, at least sometimes, of pleasure?” (If it happened only once it’s as if it never happened, p. 117)

Artur Zmijewski, born in Warsaw in 1966, was a student in the atelier of Grzegorz Kowalski, where in the 1990s important Polish artists met, such as Katarzyna Kozyra, Jacek Markiewicz and Pawel Althamer. Grzegorz Kowalski challenged his students to face the world with curiosity and pleasure and to study it, like an anthropologist, on the far side of morals and ethics. Zmijewski became well known for Eye for an Eye, a series of photos from 1998, showing naked people, some of them without legs or arms. The missing body parts were “replaced” by uninjured people “lending” their limbs. The arrangements have something comic and desperate about them, for the experiment is absurd: the missing part is not replaced but its lack is made all the more apparent. One looks again and again and discovers, for example, a man standing without legs, unembarrassed by the presence of an intact man or woman. The films Singing Lesson 1 (14’, 2001) and Singing Lesson 2 (16’30’’, 2003) work in a similar way. Deaf young people have studied the “Kyrie” from the Polish Mass by Jan Maklakiewicz or cantatas by Johann Sebastian Bach and are now singing them. The performance becomes sheer cacophony. When journalists asked “Is the point to show failure?” Zmijewski answered: “The failure of healthy people’s efforts to cause the disabled to become like them.” (If it happened only once it’s as if it never happened, p. 80)

One asks oneself why Zmijewskis documentary films are shown in the context of art. Obviously art is still a place where uncompromising presentations are possible, where they find an audience and some admiration. The documentary film, in all the variants we see on television, has not focussed on the world for a long time now, but on its viewers. It acts as if it wants to do justice to some topic, but in fact its main purpose is not to lose viewers, not to draw complaints and not to shock the advertisers’ customers. It is barely thinkable that Karolina would be broadcast – unless, perhaps, on the Arte channel. Any semi-rational television manager would ask for a balanced report: an interview with the mother, a panning shot to show the family story, a discussion with friends, a swing through the apartment and the surroundings, expert medical opinion etc. Balance as a subtle way to water opinions down. Karolina is so unbearable because Zmijewski avoids any kind of distraction and provides no image of comfort. All you get to see is Karolina; he gives her a voice, and it is the voice of endless suffering and deepest loneliness. In fact it is good that he doesn’t ask the question about sex, which doesn’t come from a real interest in the teenager but from his hope of finding a patch of light, of creating a bit of relief for himself. At the end, the last straw to cling to is the final credits – but there are none. Not a word in the style of “Karolina died xy months after filming was completed”. Even this gesture of “reconciliation” is left out by Zmijewski, because it has nothing to do with Karolina but with our need for some relief. Karolina shows us a living person, not a dead one.

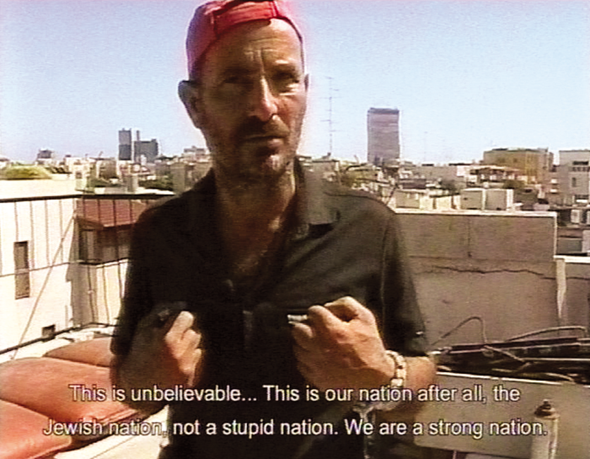

Lisa (11’, 2003) and Itzik (5’05’’, 2003) also focus on individuals, whom Zmijewski encounters with respect, calmness and inexorability. In Lisa a young German woman says that she had an illumination telling her that in an earlier life, as a twelve-year-old Jewish boy, she was killed by Nazis with a shot in the back of the head, and that God told her she must travel to Israel. Now she is living in Tel Aviv, working as a nurse, lonely and without any friends among the Jews, who find her story absurd. Itzik, whose son is serving in the Israeli army, is full of anger, and in front of the camera he makes a furious generalised attack on Arabs. His views, a mixture of historical information, Bible stories and old Jewish legends, culminate in the assertion that the holocaust gives Jews the right to kill Arabs. Lisa and Itzik are films where the viewer feels compelled to stay sitting, astonished at how incredible people can be and what prisons they build for themselves.

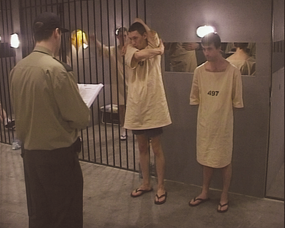

Without prejudice, without morality or shame, Zmijewski films an event that finds its first and dubious climax in 80064 (11’05’’, 2004): the artist decides to persuade a former concentration camp prisoner to have his camp number re-tattooed. Jósef Tarnawa, now a 92-year-old man and a former prisoner in Auschwitz, agrees. We see him with Zmijewski and the tattoo artist in the latter’s studio. When they want to begin the tattoo, the old man resists. Zmijewski begins to assert pressure, reminding him that he has already agreed and saying that he cannot change his mind now etc. In the end Tarnawa accepts the situation, and the number is re-tattooed in black. During the film the former prisoner explains that he survived the concentration camp because he adapted fully and submitted to circumstances, which is what is now being repeated in front of the camera. The man in front of us is no hero, and yet he is a hero for all that. As 80064 runs on, our attention shifts from Tarnawa’s story to the question of whether the other two will really dare to refresh the camp number. In this way the viewer takes the leading role, becoming an accomplice to the film and Tarnawa himself becomes an extra – this is the way conventional documentary films work.

In his cooperation with the actor Wojciech Królikiewicz, Zmijewski achieves a beautiful tight-rope act between exposure and dignity, performance and life, control and freedom. Królikiewicz suffers from Huntington’s disease, he is able to coordinate his muscles only with the greatest effort, so that the simplest everyday activities become a huge challenge and end in loss of breath. Rendezvous (8’, 2004) shows Królikiewicz getting up and dressing himself, while his grotesque movements resemble a dance. A bit later he meets Danuta Witkowska, who also suffers from Huntington’s disease. Together they eat a pizza in a restaurant, go for a walk in the park, their twisted movements making it seem as if they are imitating disabled people. As in Eye for an Eye, Karolina and Singing Lesson 1 or Singing Lesson 2 people expose themselves naturally and with dignity. They show that the forces of society, history and even democracy, in trying to establish standards and insist on conventions, are a constant threat to freedom. And that their bodies are always a battleground.

In the installation William Shakespeare, Sonnets Wojciech Królikiewicz reads a selection of Shakespeare’s sonnets and in every word one can hear the effort it costs him. On a monitor one can see how, with his jerking limbs, he tears up the books he is reading from. They lie as remains in a glass case next to him and the laconic comment comes down on us like a hammer: in comparison to life, art is ridiculous, and yet it lives longer than we and – at least for moments – fulfils us.

Translated by Nelson Wattie

DANIEL BAUMANN lives in Basel and is Conservator of the Adolf-Wölfli-Stiftung in the Bern Art Museum as well as project manager of Nordtangente-Kunsttangente [North Tangents Art Tangents] in Basel.

ARTUR ZMIJEWSKI, born 1966 in Warsaw, 1990–95 studies sculpture at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, 1995 graduates in the studio of professor Grzegorz Kowalski, 1999 Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam. Lives in Warsaw.

Represented by FOKSAL GALLERY FOUNDATION, Warsaw; GALERIE PETER KILCHMANN, Zurich