Ciprian Mureşan & Adrian Ghenie, Ceauşescu’s Portrait, 2008

Communist? Me too!

Marxism is still the most thoroughgoing, salient and trenchant critique of capitalism, a system which – more than ever – needs critics and rivals. NICK CURRIE looks at artistic projects bringing communist themes into play.

Art can be »political«, but the moment it actually becomes politics it finds its wings clipped: the endless symbolic freedom which is art’s most »political« strength ends as soon as it gets mired in the practical logistical problems of real world politics. The condition of art’s symbolic power is, paradoxically, a certain pragmatic impotence. Joseph Beuys is not remembered for representing the Green Party in Parliament, but for filling rooms with felt and fat and coyotes and hares. His most important work was »political«, but not politics.

But artists are fascinated with politics, and particularly the politics that most resembles their own activity – the politics of utopias, of the possible, of the alternative, and of world-transformation. Currently, communism is outside the so-called »Overton Window« of acceptable social democratic politics in the West (the rhetorical device by which politicians try to portray their rivals as »dangerous extremists«, frightening the public into acceptance of a bland and limited centrism). As a result, communism is a repressed, fascinating spectre that stalks the Western art world.

There’s currently a rash of exhibitions, conferences, initiatives and events in Europe themed around communism. At Nottingham Contemporary in England in March I saw Star City: The Future Under Communism, a show which looked at communist projections into the Modernist future, the symbolism of cosmonauts, propaganda, and so on. The exhibition mixed future-themed historical records from Communist nations with contemporary art by, for instance, Pawel Althamer, whoseCommon Task project explores unrealised utopian communitarianism.

Searching for the Post-Capitalist Self is the title of the summer edition of art journal E-Flux, guest-edited by artist and curator Marion von Osten, and tied into the 6th Berlin Biennale. It appears in June. That same month, the Berlin Volksbühne hosts an interdisciplinary congress calledThe Idea of Communism: Philosophy and Art. I will personally haunt this event – initiated by Alain Badiou and Slavoj Zizek – as an unreliable tour guide. Meanwhile, artists and critics will investigate – in performances, panels, installations, films and concerts – communism as an idea, its »actually-existing« history, and its potential for the future.

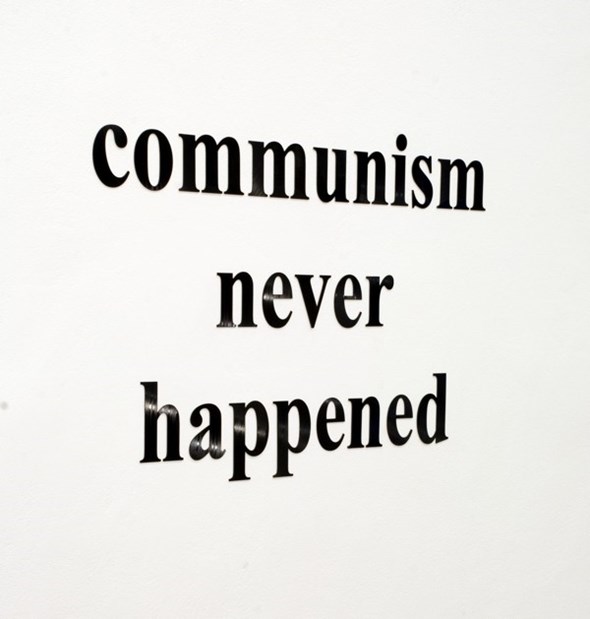

Ciprian Mureşan, Communism Never Happened, 2006

One reason all this is happening now is that we’re at »the curatorial distance« (the length of time it takes curators to organise shows and events) from the great financial crisis of 2008, which shook everyone’s confidence in the basic soundness of the free market model and the inherent rational efficiency of Adam Smith’s »hidden hand«. A bigger reason is that there’s a general sense in culture as a whole that we’ve come to the end of a distinct thirty-year period dominated by the neo-liberal idea that everything can be resolved by unfettered markets and freedom of individual choice. Tony Judt’s new book Ill Fares the Land (Penguin, 2010) shows that thirty years of Anglo-Saxon pro-market reforms have resulted in rising inequality, stunted social mobility, poorer health and life expectancy, higher crime and more mental illness than are found in comparably advanced societies in which firm state control is the norm.

As society at large turns the page on the neo-liberal project, the art world too shifts: 2009 saw Nicolas Bourriaud launch a Tate Triennial which boldly proposed the era of postmodernism over, and suggested that a new cultural era had arrived. He called it the »altermodern«. For Bourriaud, the term – still vague, as it should be – is something to do with discovering alternative modernist ideals in translation and the multi-polar model of a horizontal, post-colonial globalisation.

Bourriaud doesn’t spell out the charge that the postmodernism his altermodernism seeks to replace was complicit, hand in glove, with the neoliberal project, but it’s a conclusion hard to avoid. Watch Sandy Nairne’s 1987 television series State of the Art, for instance, and you’re struck by the extent to which art in the 80s had become a field in which identity politics played out symbolic reparations for real injuries to real people: natives dispossessed by colonial adventures, women oppressed by patriarchy, blacks up against apartheid, gays besieged by AIDS. The resulting micro-politics of identity fail to phase the 80s politicians, seen in State of the Art opening 80s biennials sponsored by 80s banks. At the end of his 2002 essay A Singular Modernity Frederic Jameson writes: »Radical alternatives, systemic transformations, cannot be theorized or even imagined within the conceptual field governed by the word ›modern‹.« We need another context, because terms like »modern« and »postmodern« are all too easily made synonymous with the capitalism that produced them, if we follow the classic Marxist idea that art and culture are circumscribed by pre-existing economic conditions. Instead, says Jameson, »what we really need is a wholesale displacement of the thematics of modernity by the desire called Utopia.«

So will things be different this time around? Will the artists of the new altermodernity be able to reload communist themes in ways that go beyond identity politics and symbolic reparation? Will superstructure somehow transcend base? Can the future be produced by the present? Will a common front emerge? Or will this just turn out to be an intellectual fashion, the kind of radical chic Dali nailed when he quipped: »Picasso is a Communist, me neither«?

Or perhaps escape from economic determinism, and therefore from history’s dialectic, is not the point. As Jameson says in his book Valences of the Dialectic, it is precisely the worldwide triumph of capitalism that »secures the priority of Marxism as the ultimate horizon of thought in our time«.

NICK CURRIE is a musician and artist. He lives in Berlin.

Images contributed by CIPRIAN MURESAN

As society at large turns the page on the neo-liberal project, the art world too shifts: 2009 saw Nicolas Bourriaud launch a Tate Triennial which boldly proposed the era of postmodernism over, and suggested that a new cultural era had arrived. He called it the »altermodern«. For Bourriaud, the term – still vague, as it should be – is something to do with discovering alternative modernist ideals in translation and the multi-polar model of a horizontal, post-colonial globalisation.

Bourriaud doesn’t spell out the charge that the postmodernism his altermodernism seeks to replace was complicit, hand in glove, with the neoliberal project, but it’s a conclusion hard to avoid. Watch Sandy Nairne’s 1987 television series State of the Art, for instance, and you’re struck by the extent to which art in the 80s had become a field in which identity politics played out symbolic reparations for real injuries to real people: natives dispossessed by colonial adventures, women oppressed by patriarchy, blacks up against apartheid, gays besieged by AIDS. The resulting micro-politics of identity fail to phase the 80s politicians, seen in State of the Art opening 80s biennials sponsored by 80s banks. At the end of his 2002 essay A Singular Modernity Frederic Jameson writes: »Radical alternatives, systemic transformations, cannot be theorized or even imagined within the conceptual field governed by the word ›modern‹.« We need another context, because terms like »modern« and »postmodern« are all too easily made synonymous with the capitalism that produced them, if we follow the classic Marxist idea that art and culture are circumscribed by pre-existing economic conditions. Instead, says Jameson, »what we really need is a wholesale displacement of the thematics of modernity by the desire called Utopia.«

So will things be different this time around? Will the artists of the new altermodernity be able to reload communist themes in ways that go beyond identity politics and symbolic reparation? Will superstructure somehow transcend base? Can the future be produced by the present? Will a common front emerge? Or will this just turn out to be an intellectual fashion, the kind of radical chic Dali nailed when he quipped: »Picasso is a Communist, me neither«?

Or perhaps escape from economic determinism, and therefore from history’s dialectic, is not the point. As Jameson says in his book Valences of the Dialectic, it is precisely the worldwide triumph of capitalism that »secures the priority of Marxism as the ultimate horizon of thought in our time«.

NICK CURRIE is a musician and artist. He lives in Berlin.

Images contributed by CIPRIAN MURESAN

Ciprian Mureşan, Leap into the void, after 3 seconds, 2004