»I worked in obscurity«

With only five subversive low-budget productions STEPHANIE ROTHMAN became a legend of American exploitation movies in the 1970s. This year the Viennale is paying her a tribute. By JUDITH FISCHER

During my obsessive occupation with vampire films, Stephanie Rothman’s The Velvet Vampire (1970) was long no more than a phantom of a film. A few stills and plot summaries were in circulation (A Dune Buggy in the Desert, This Place grows on you). And then, at last, I saw The Velvet Vampire, where the female vampire, Diane le Fanu, lives in a modernist house in the desert and allures a young (married) couple to join her, having met them at an opening in the Stoker Gallery. (Neither then nor today will Stephanie Rothmann respond to my question whether she has seen films by people like Jess Franco or Jean Rollin.)

Rothman became known for her exploitation films in the 1970s, low budget productions, behind whose often »primitive« basic ingredients »coded with comedy« (Rothman), a radical, critical subplot can be found, as Robin Wood noted when he invited her to the horror-film series, The American Nightmare at the Toronto Film Festival in 1979. The film scholar Pam Cook was also a loyal supporter of her films: exploitation as counter-cinema. Stephanie Rothman became an American director who was often marginalised but also found a critical and empathetic reception. For herself – partly due to the restructuring of the cinematic landscape at the end of the 1970s – she made different career decisions, becoming a state lobbyist for Californian universities and later the owner of real estate in Los Angeles. »I’ve become a capitalist,« Rothman said in the conversation.

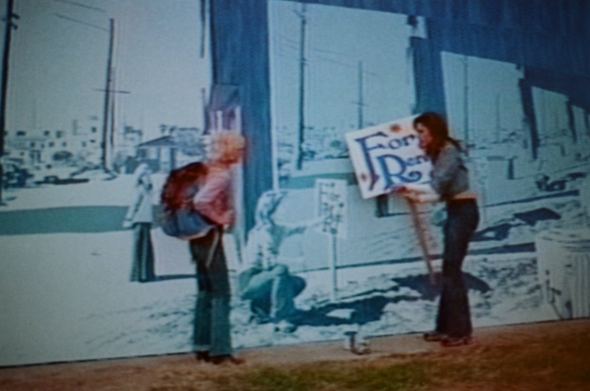

In some of her films Rothman mixes a friendly, harmless softcore world full of the joys of life with an impulsive longing to create new, successful Utopian communes and formal groups with binding rules – as in The Student Nurses (1970): charming, long-haired women with a central parting live together in a four-person apartment, are inexperienced, but willing to learn and totally without any tendency to introspection, wear skirts that are too short, no bras of course, and hop across the meadow gathering flowers, have a date with a vegetarian and spin on bikes through Los Angeles, eat candyfloss and have art prints on their walls, watch the Living Theatre on the theme of Mexican immigrants and fight for »public health« and the right to abortion, paint a male nude model and: run, drive, walk, flit around – nothing ever stands still … Terminal Island (1973), by way of contrast, is a gloomy heterotopy (with a full-bearded and, at that time, unknown Tom Selleck) about a kind of proto-revolutionary change of government on an island, where female convicted murderers are isolated. In The Working Girls (1974), in addition to the need for women to go job-hunting to earn their living, Stephanie Rothman also shows images of women as artists. And, with Rothman seemingly caricaturing herself in a tender and precise way, the painter is commercially employed as a poster painter. When she wants to let her room, she paints the »Room to Let« sign and the real surroundings on a wall of the building. In the film we see the painter finish painting the scene, where (precognition?) the future tenant can already be seen, who later says »I thought it is only a picture«. For Rothman the fine arts in the form of painting and sculpture are an important point of reference, »because it is a matter, just like film, of composition, lighting and texture.«

In looking back on her own films I ask Stephanie Rothman how she sees them now, from the distance of her own passing life. Stephanie Rothman: »That’s a good question. I remember the pleasure or pain a scene gave me. It’s a flood of memories and I am pleasantly surprised. They are not as horrible as I thought. I see that they have significance & relevance and I see their timeliness and their timelessness.«

Translated by Nelson Wattie

JUDITH FISCHER is an author and artist living in Vienna.