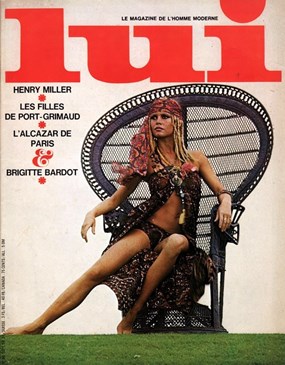

lui, cover, September 1969

One’s own thing

What contribution do niche magazines make to cultural life? JOACHIM BESSING takes a look at some fashionable magazines and finds both a potential to resist and a degree of mannerism.

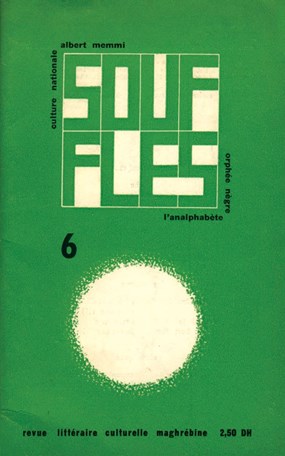

The casual comment of the bulk publisher Axel Cäsar Springer, to the effect that »Yesterday’s newspaper is the paper the fish is wrapped in tomorrow«, was always only relatively true of the journals and magazines related to newspapers. Those interested in fashion are searching intensely for the now scattered copies of Die Dame, the journal that appeared in Germany around the turn of the century; bachelors with taste are decorating their coffee tables with issues of the French men’s magazine Lui (but only those from the years 1971-78). In artistic circles, issues from this period of the North African fanzine Souffles are being hunted down, and anyone lucky enough to have saved all eight issues of Aspen Magazine can now comfortably demand ten thousand euros just for this really slim collection of journals (the subscription price in the late 1960s was 16 dollars per issue) – this sum being no less comfortably counted out by a collector who thinks he is even luckier. This journal, put out by the former editor of Women’s Wear Daily, Phyllis Johnson, between 1965 and 1971, was really something special: each issue was in a prettily designed box while the contributions consisted of loose insertions in various formats (including vinyl disks), according to the curatorial principle each issue was put together by a new editor in chief, and the advertisements were discreetly concealed on the bottom of the box (while the last issues managed without any at all).

Aspen Magazine became so highly valued because a large number of today’s so-called niche magazines see their origins in its editorial and conceptual principle: the curatorial approach in fact, the holistic claim, no less, with regard to the integration of all possible media formats and contributors, and finally, with a principled border-crossing in the form itself – medium or multiple? It is and it isn’t, actually: it’s both, and fundamentally with a strong urge towards the unique.

An editorial counter-position to Axel Cäsar Springer, and to William Randolph Hearst, Joseph Pulitzer, Rupert Murdoch or Condé Montrose Nast couldn’t be formulated more crudely; at times it seems that only a few makers of so-called niche titles are interested in finding a broad readership with their medium, becoming a new Vogue, or a new Artforum– in street jargon, making a profit. The magazines Editor & Art Director from the United States, Kasino A4 from Finland, Nico from Luxemburg, Nuke from France or This is a Magazine / This is not a Magazine from Italy make it clear even in their choice of title: no paper for the kiosk next door (where Vanity Fair, Vogue and the news magazines are on display), our magazine belongs in the concept store. As an alternative, it is sold in the gallery we trust or is only available at the airport (because our readers make their purchases nowhere else).

Considering the loving way they are made, regarding both their graphic design and their production values in such matters as grades of paper, printing processes, binding methods etc., in any case one gets the impression that these are intended to be book objects rather than mere wrapping paper for tomorrow’s fish.

Souffles, cover 1967

The concept of a »playing field« forces its way up in all its ugliness. After all, »unprofessional« has advanced to become the coup-de-grace argument of the twenty-first century, and being professional is a straightforward matter of profitable work. For the production of niche magazines, financial incisions are to be borne partly because of their inherent deficiencies regarding circulation and the related page prices on the advertising market, and these make publishers of this kind look like true believers rather than serious competitors in the media industry. »A nice hobby«, is the expert judgement of tax officials, bank managers and bulk publishers. Of course, anyone working for a publication of this kind earns almost no money from it, and whoever cooperates with such a medium as a photographer or writer usually earns nothing at all (that will have been no different in the case of Aspen Magazine, if one just considers the price of copy at that time). And yet, all the same, the e-mail in-boxes of the editors of these niche journals – whether for texts or images – overflow with requests for printing commissions, for there you can still do what doesn’t work anywhere else.

The pressure of advertising customers on editorial teams who run a normal business is enormous. Anyone who wants to earn a living as a professional journalist, a professional photographer, a stylist etc. mostly has to do jobs that can hardly add a shine to their portfolio. Right at the top, in the reality of five-figure daily fees (for photographers) and four-figure printout fees (for texts) the air has grown no thinner; there is as much room there now for as many good people as there was in the 1970s and 1980s. However, the number of journals has grown by a factor of at least ten, and the market is globally organised, which means that one not only has to prove oneself in the local shark pool but also has to survive in front of the international crème de la crème.

The revolutionary impulse, which also played a decisive role in the case of Aspen Magazine, seems to grow directly out of the above mentioned conditions of today’s journalistic marketplace; no longer wanting to play the game, being able to make something »of one’s own«, making up the rules oneself to a large extent, that seems important enough to take on the enormous work of a financially fruitless publishing activity. Wanting to a make a contribution? To culture perhaps? No doubt. That also has a role to play, for sure. But one thing should be clear already – the term »niche magazine« is misleading in most cases. It is in fact seldom a matter of a magazine produced for a niche, in other words offering subject matter that has been either undervalued or overlooked by »the big ones« because of a lack of »underground competence« or the good old distinguishing criterion of »good taste«.

No, niche journals are called that by professional journalists because they have settled down comfortably in their niche. And the revolutionary impetus is such that it can all too quickly mature into mannerism. And so, for example, when the editor-in-chief of a German niche journal recently asked an English adviser about a recommended guideline for his next issues, the Englishman answered at once: »Make it strange. Make it less – understandable.«

Translated by Nelson Wattie

JOACHIM BESSING is a writer and teaches fashion journalism at the Akademie für Mode und Design in Berlin.

The pressure of advertising customers on editorial teams who run a normal business is enormous. Anyone who wants to earn a living as a professional journalist, a professional photographer, a stylist etc. mostly has to do jobs that can hardly add a shine to their portfolio. Right at the top, in the reality of five-figure daily fees (for photographers) and four-figure printout fees (for texts) the air has grown no thinner; there is as much room there now for as many good people as there was in the 1970s and 1980s. However, the number of journals has grown by a factor of at least ten, and the market is globally organised, which means that one not only has to prove oneself in the local shark pool but also has to survive in front of the international crème de la crème.

The revolutionary impulse, which also played a decisive role in the case of Aspen Magazine, seems to grow directly out of the above mentioned conditions of today’s journalistic marketplace; no longer wanting to play the game, being able to make something »of one’s own«, making up the rules oneself to a large extent, that seems important enough to take on the enormous work of a financially fruitless publishing activity. Wanting to a make a contribution? To culture perhaps? No doubt. That also has a role to play, for sure. But one thing should be clear already – the term »niche magazine« is misleading in most cases. It is in fact seldom a matter of a magazine produced for a niche, in other words offering subject matter that has been either undervalued or overlooked by »the big ones« because of a lack of »underground competence« or the good old distinguishing criterion of »good taste«.

No, niche journals are called that by professional journalists because they have settled down comfortably in their niche. And the revolutionary impetus is such that it can all too quickly mature into mannerism. And so, for example, when the editor-in-chief of a German niche journal recently asked an English adviser about a recommended guideline for his next issues, the Englishman answered at once: »Make it strange. Make it less – understandable.«

Translated by Nelson Wattie

JOACHIM BESSING is a writer and teaches fashion journalism at the Akademie für Mode und Design in Berlin.