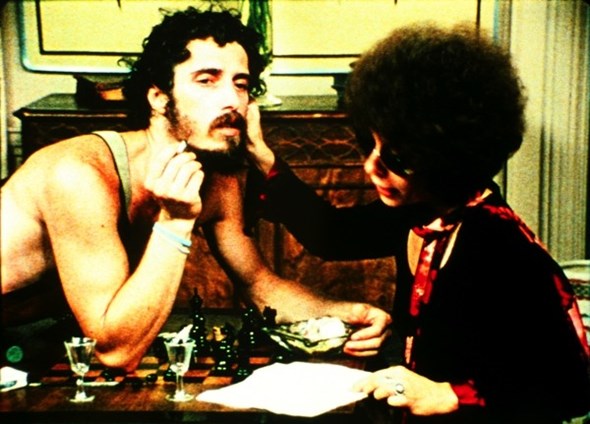

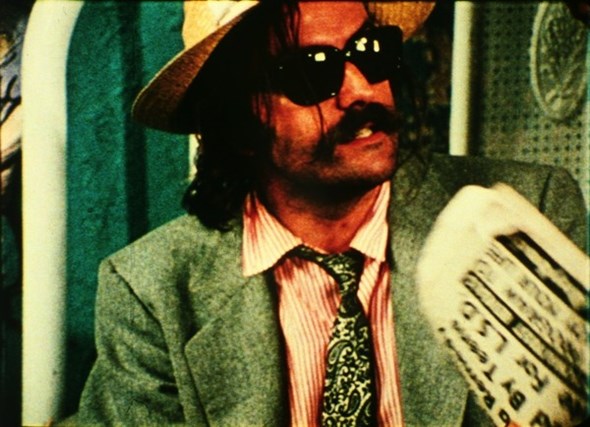

Courtesy Anthology Film Archives, New York

JAY SANDERS, Co-Curator of the 2012 Whitney Biennial, on the film trilogy Dr. Chicago (1968–1971) by George Manupellis

Horrors of Malformed Men, a 1969 cult horror film by Japanese director Teruo Ishii, provides an unlikely but essential document from maverick artist-choreographer Tatsumi Hijikata. The originator of Butoh, Hijikata had for years performed his dance-theater spectacles throughout Japan, but was reticent to fully document them, wary of their relocation to more stable media. While early film fragments exist, shrouded in shadows and jittery from handheld 8mm camerawork, Ishii’s extravagant full-color movie features extended scenes of Hijikata’s wild visionary dancing on an appropriately tumultuous rocky beach, dispatching key Butoh choreography from the era. However, few film viewers would have recognized it as such, instead seeing these gesticulations as his character’s clearly unstable inner-psyche – Hijikata stars as a mad-scientist living on a remote island where he conducts crude and grotesque biological experiments aimed at deforming society.

This rare hybrid of avant-garde activity folded into feature-film genre narrative finds an unexpected extreme in the recently restored Dr. Chicago trilogy. American artist/director George Manupelli drew on the extended community circling the infamous ONCE Festival, a vanguard new music and multi-media event held in Ann Arbor, Michigan during the 60s. Experimental music composer Alvin Lucier became his unlikely star, as Dr. Alvin Chicago, an unsavory but endearing sex-change doctor on the run from the police with a cast of hangers-on. What sets the film’s tone and pacing is Lucier’s pronounced stutter – a chronic real-life affliction that is magnified exponentially as the film is comprised primarily of the rambling half-improvised soliloquies. With diagnoses such as »we’ll have to make some minor adjustments in your body-y-y, your b-body t-t-t-t-emperature, perhaps bring it up a few degrees,« Lucier resolutely chatters through all three films – Dr. Chicago (1968), Ride Dr. Chicago Ride (1970), and Cry Dr. Chicago (1971).

Other luminaries populate Dr. Chicago’s cast and crew. Composer Robert Ashley provides the soundtrack, and his wife at the time, performance artist Mary Ashley, plays Chicago’s wife. Composer Pauline Oliveros, future food critic Ruth Reichl and mime Claude Kipnis also participate on-screen. But the primary counterweight to Dr. Chicago’s incessant monologue is the haunting presence of dancer Steve Paxton as »Steve«, an unexplained mute sidekick who dies at the end of each film, only to reappear in the next. A founding member of Judson Dance Theater and Grand Union, Paxton performs some of the most raggedly beautiful, spaced-out choreography ever committed to film – aiding a sick girl by plastering her with soggy oak leaves, performing a string and scissor magic trick so slowly that the suspense is lost, joining in as a character convulses from a seizure in an impromptu contact-dance, and wrapping Dr. Chicago up in gauze as he puffs away on a cigar. As with Hijikata’s film foray, Paxton’s astoundingly beautiful and specific dance inclusions are redefined by a landscape – whether desert trails, a log cabin hideout, or an elegantly furnished villa.

Courtesy Anthology Film Archives, New York