MAI-THU PERRET

Klaus Theweleit: Male Fantasies

Christian Egger: One really simple question to start with: when did you first become aware of Klaus Theweleit’s "Male Fantasies", and what impression did you get from them?

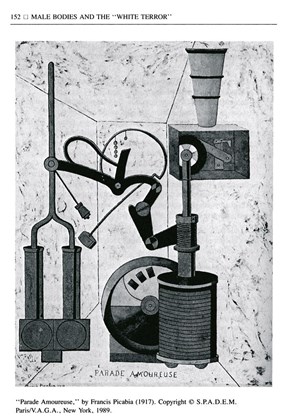

Mai-Thu Perret: A couple of years ago, my friend Carissa Rodriguez was visiting Berlin and told me about the book. It sounded really interesting, and the fact that I was living in Germany at the time was also an incentive. Since my German is so bad I ordered the English translation via internet. The first thing I noticed was the very unusual style, the mixture of a very personal, very passionate voice, with the close reading of textual sources. The other was the highly original use of images in the book. There is a kind of parallel narrative within the book established by Theweleit’s very cultivated and humorous choice of visuals. They are very rarely just "illustrations" in the traditional sense of the words: very often the pictures are not from the period at all but rather the product of a kind of free associative mind looking for pictures that act as a counterpoint to the text in a very idiosyncratic manner. It’s clever to use a Picabia drawing of a woman’s naked body seen from the rear surrounded with the word "literature", floating around her like water, or a Robert Crumb comic to illustrate a book about the horror of the feminine in the German Freikorps soldiers of the early 1920s.

It brings the very particular material and focal point of the book in contact with wider, and more contemporary concerns (the German New Left, the anti-authority movements of the 1970s).

Text seems to play an important role in your work. What do you still find useful for yourself in Theweleit’s unacademic and, at that time, (1977) pioneering approach in his meticulous studies of the relations between misogyny and fascism, grounding this configuration very precisely in the particularities of time,place,culture,and social class (incorporating body, gender and psychoanalytical theory)?

The most interesting thing about Theweleit is that he manages to avoid two pitfalls of academic writing: on the one hand, it is not "theory", it is extremely empirical and refuses to see male violence and domination as a universal and monolithic thing, and on the other it is not just an historical study: his material clearly has some relevance to current relationships between men and women. The unconscious link between the attitude of the Freikorps and the more civilized forms of misogyny at work in the 1970s (or in other parts of the 20th century for that matter) is brought home by the way the pictures refuse to simply illustrate the text and spill over into a free associative pattern that binds the then and the now together. Of course you can say that Theweleit’s book is flawed. There are, for example, some passages about the past of the human race as an amphibious race [species?] that felt highly dubious when I read them, but the most important thing about it is precisely that it takes the risk to be flawed and militant. By giving such a detailed, sociologically grounded account of male violence in the Freikorps, it also shows you a way towards undoing that violence, in everybody’s personal life. Theweleit refuses to read violence as a symptom of something else, he demands that it should be confronted as what it is. This literalness is very empowering and reminds me of what I like best about Deleuze and Guattari, whose influence is very palpable in the book. Now when it comes to the question of the relationship between this kind of text and my work, I’m not sure. In some ways I also refuse to read one thing for something else, and most of the reading I do has little to do directly with my work. I like to read for reading’s sake, and any book I like I like beyond what use I could put it to in my work. But of course you could also say that it’s precisely this love of reading for reading’s sake that explains why my work incorporates so much text.

On the copy of "Male Fantasies" that I have, the cover shows Bruce Nauman’s "Marching Man" ... what’s on yours? Would the marching man be a welcome guest on "Crystal Frontier"? And how would you describe "Crystal Frontier" to someone unfamiliar with this project of yours?

My copy is the University of Minnesota Press Translation, in the „Theory Out of Bounds“ series. What’s most noticeable about it is the font used for the title, a rather crude gothic black face where the dagger like f of "fantasies" is overlaid with red at the tip as though it was blood. Not exactly subtle. Then there is a rather mysterious image of boots, also black with a red halo. It’s by an artist called Mary Griep, who I’ve never heard of. I had to google ”Marching Man“. It’s a neon piece showing a cartoon man marching, his front leg vertical and his penis pretty glaringly erect. I don’t think he’d be very much liked by the characters of the ”Crystal Frontier“. The ”Crystal Frontier“ is the name of a fictional autonomous community that is the putative author, or referent, of the artworks I make. It’s a group of women who live in the desert, away from the city and modern, capitalist society, trying to start from scratch and to create a new relationship to work, nature and themselves. The story is only vaguely sketched out, through discontinuous textual fragments such as diary entries, letters, flyers etc. I first started making the work of the commune members because I was looking for a way to remove myself - the inevitable tendency to autobiography and personal taste - from my own work. At the beginning it was a way to work within set parameters, and then see what would turn up. A bit like the moment in conceptual art, when Sol Lewitt says that "the idea is the

machine that makes the art", but using a more complex fictional machine. The project has grown in many unexpected ways since then.

In the afterword of the paperback edition Theweleit says that the author knows in a kind of telepathic way how his things got through and were accepted by the reader and the rest may remain in the dark (explaining why he doesn’t answer readers’ letters). Is this something you would also agree with in terms of (your) art? And how do you deal with the concept of authorship in general?

If I understand you, you are asking me about the author’s relationship to his work after it’s been created and put out there for others to read or see. I’m not really an expert on Theweleit, I just read his book, so I didn’t know he refused to answer letters. I wouldn’t be so drastic (but then I will probably never get as many letters as he does; his book must have seemed extremely polemical when it came out). In general I don’t like to strongly determine the way the work is interpreted. The narrative I provide as an explanation of my work is so flimsy and at times bizarre that it’s impossible to take it as the only reading for the work. It is a particular tool for making the work and thinking about it, but the work is clearly not univocal. When you look at a particular piece there are other things that add up in addition to the commune narrative, such as historical references etc. I’m interested in that openness.

Theweleit: „The making and structure of the book [...] are unacademic and aerated with pictures, and explicitly anti–philosophic, and as nowhere else with exception of mathematics and religious scholasticism the skeleton of male concept is more rigid and abrasive than in the various philosophical schools from the ancients to Adorno [...], that therefore it was male fantasies’ intention to develop a different tone."

Could it be a different view you’re after, by citing modernisms, aestheticisms and many diverse 20th century references in your investigative approach to art?

Interesting that you ask this question. If anything, my use of modernist images and references is a revisionist take on art history. If you spend a little bit of time reading about „modernism“ the standard construction of it as a rational, progress bound, male dominated endeavour starts to fragment into a myriad of much more varied views, with countless minority figures and forgotten voices. I’m interested in the road not taken, the shape that things didn’t take but could have, and I think it’s in that spirit that I look at images from the past. Theweleit is speaking about something very different, about the philosophical tradition, which is an academic tradition and as such much more authoritarian than the art I look at.

You mentioned that you are a rather distracted reader, reading different books at the same time. You think this is what makes it difficult for a book to become an art theory classic instantly read by all, as many contemporary colleagues work/read that way today or rather you assume that it has been always like this?

But it’s probably true that right now, as opposed to the 1960s, 1970s or even the 1980s, we are in a much more pluralistic, probably less interesting period for philosophy, or "theory". I’m not sure that this is something to be so sad about, things come and go in cycles and just as people are complaining about being at a low cycle something really amazing comes out and changes our perception. But in the past five years there hasn’t been a central book used as reference point to talk about art in the way that, for example, Jean Baudrillard was important for the art world of the 1980s. Now I don’t really think that Baudrillard is that great, so I’m not sure we’re actually missing out on anything by not having a big art theory fashion right now. The other thing is that people read differently in different times of their life. I studied philosophy and literature at university, so I was trained to read a book linearly from start to finish, I even remember trying to understand books by taking notes so detailed that they became useless and almost as long as the books themselves. After a while you start doing other things in your life than sitting in the library, and you start being a bit more casual in your attitude to reading. I still read a lot of fiction and I always read novels from the first page to the last. But some other books are ok to read in a more fragmented way, you still pick up things for your personal toolbox that way.

Maybe it’s dreadful to ask , but if ”The Crystal Frontier" was only a book, what would be the most significant differences compared to the body of art pieces and what would it obviously lack?

I don’t think ”The Crystal Frontier“ could be only a book. It would be extremely short, and quite boring to read because it would lack all sense of narrative development. Maybe it could be tightly wound poems. The artworks are what enables it to exist as fragments through time.

KLAUS THEWELEIT »male fantasies, volumes 1 + 2«, University of Minnesota Press, 1987 and 1989

CHRISTIAN EGGER is an artist and lives in Vienna.

MAI-THU PERRET * 1976 in Geneva. Recent one person shows include “And Every Woman Will Be a Walking Synthesis of the Universe”, The Renaissance Society, Chicago (2006) “Apocalypse Ballet”, Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin (2006), and “Solid Objects” (with Valentin Carron), Centre d'art contemporain, Geneva (2005). Since 1999, she has been writing fragments of “The Crystal Frontier”, a fictional account of a group of women who found an autonomous commune. Parallel to the written text, artworks are created and exhibited as the women’s hypothetical production. Mai-Thu Perret lives and works in Geneva and New York.

Interesting that you ask this question. If anything, my use of modernist images and references is a revisionist take on art history. If you spend a little bit of time reading about „modernism“ the standard construction of it as a rational, progress bound, male dominated endeavour starts to fragment into a myriad of much more varied views, with countless minority figures and forgotten voices. I’m interested in the road not taken, the shape that things didn’t take but could have, and I think it’s in that spirit that I look at images from the past. Theweleit is speaking about something very different, about the philosophical tradition, which is an academic tradition and as such much more authoritarian than the art I look at.

You mentioned that you are a rather distracted reader, reading different books at the same time. You think this is what makes it difficult for a book to become an art theory classic instantly read by all, as many contemporary colleagues work/read that way today or rather you assume that it has been always like this?

But it’s probably true that right now, as opposed to the 1960s, 1970s or even the 1980s, we are in a much more pluralistic, probably less interesting period for philosophy, or "theory". I’m not sure that this is something to be so sad about, things come and go in cycles and just as people are complaining about being at a low cycle something really amazing comes out and changes our perception. But in the past five years there hasn’t been a central book used as reference point to talk about art in the way that, for example, Jean Baudrillard was important for the art world of the 1980s. Now I don’t really think that Baudrillard is that great, so I’m not sure we’re actually missing out on anything by not having a big art theory fashion right now. The other thing is that people read differently in different times of their life. I studied philosophy and literature at university, so I was trained to read a book linearly from start to finish, I even remember trying to understand books by taking notes so detailed that they became useless and almost as long as the books themselves. After a while you start doing other things in your life than sitting in the library, and you start being a bit more casual in your attitude to reading. I still read a lot of fiction and I always read novels from the first page to the last. But some other books are ok to read in a more fragmented way, you still pick up things for your personal toolbox that way.

Maybe it’s dreadful to ask , but if ”The Crystal Frontier" was only a book, what would be the most significant differences compared to the body of art pieces and what would it obviously lack?

I don’t think ”The Crystal Frontier“ could be only a book. It would be extremely short, and quite boring to read because it would lack all sense of narrative development. Maybe it could be tightly wound poems. The artworks are what enables it to exist as fragments through time.

KLAUS THEWELEIT »male fantasies, volumes 1 + 2«, University of Minnesota Press, 1987 and 1989

CHRISTIAN EGGER is an artist and lives in Vienna.

MAI-THU PERRET * 1976 in Geneva. Recent one person shows include “And Every Woman Will Be a Walking Synthesis of the Universe”, The Renaissance Society, Chicago (2006) “Apocalypse Ballet”, Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin (2006), and “Solid Objects” (with Valentin Carron), Centre d'art contemporain, Geneva (2005). Since 1999, she has been writing fragments of “The Crystal Frontier”, a fictional account of a group of women who found an autonomous commune. Parallel to the written text, artworks are created and exhibited as the women’s hypothetical production. Mai-Thu Perret lives and works in Geneva and New York.